Will the Second Leg of the Banking Union Be Limping?

Adelina Marini, December 12, 2013

The current dilemma in the European Union is how to make an omelette without breaking the eggs. It is already turning into a tradition for difficult tasks to seek an intergovernmental solution. This is what happened with the fiscal compact. With the second pillar of the banking union a much more complex creature is to emerge - an odd hybrid between an intergovernmental agreement and a community approach. At least this is how things look like a little before the final denouement planned for next Wednesday (December 18th), when the economic and finance ministers will meet extraordinarily with the ambition to strike a deal on the resolution mechanism before the last for the year EU summit on December 19-20.

The current dilemma in the European Union is how to make an omelette without breaking the eggs. It is already turning into a tradition for difficult tasks to seek an intergovernmental solution. This is what happened with the fiscal compact. With the second pillar of the banking union a much more complex creature is to emerge - an odd hybrid between an intergovernmental agreement and a community approach. At least this is how things look like a little before the final denouement planned for next Wednesday (December 18th), when the economic and finance ministers will meet extraordinarily with the ambition to strike a deal on the resolution mechanism before the last for the year EU summit on December 19-20.

Along the smallest resistance

As a matter of fact, the dilemma is much bigger, but no one has the time nor the energy to deal with it. The existing treaties of the EU do not allow seeking a solution to ever more intricate issues stemming from the deepening of the European integration and the as dynamic disintegration forces, led by Britain. Since that June EU summit, when the leaders of the 27 (without Croatia then) showed ambition and decided to go for a banking union that would break the draining-budgets-and-jobs connection between a sick banking system and the sovereign, a lot of time has passed. UK in the meantime has started actively to work for renegotiation of its situation in the Union as there are even trainings of how exactly will the negotiations take place. The culmination will be in 2017 when it is possible a referendum to take place on whether the UK should stay in the EU or go.

And while Britain is preparing and is analysing the impact of the European legislation over the independent and islandish spirit of British citizens and politicians, similar analyses are already under way in The Hague and soon in Helsinki. The European dream is turning into a memory from the first romantic dinner. Now the situation resembles rather a marriage stuck in the dilemma a divorce or we're-too-old-and-too-tired-for-new-relationships. What has been achieved so far makes many at the negotiations table in Brussels nervous by excessive interference of the EU in their lives. They are put in imbalances procedures, they are required to reduce the deficit, to do certain reforms which are deliberately postponed for the sake of higher electoral scores. And now, a solution is needed to the problem with saving systemic banks that work in more than one EU member state. And according to Internal Market Commissioner Michel Barnier, their number is 250.

What should the Future of Europe be then against this background? Minimalistic, is the answer that can be heard in Frankfurt and in many EU capitals. On December 6th, Benoît Cœuré, member of the executive board of the ECB, said in Frankfurt during the fifth German Economic Forum, that Europe did not need a "quantum leap" in its integration, of such often call MEPs in Strasbourg every time when an important issue is discussed. Rather, Mr Cœuré believes, what is needed is to complete what has been started in 1999, which is to complete the economic and monetary union (the eurozone). He explained things very simply. Regarding banking supervision and bank resolution there are serious grounds for centralisation. It is also clear that the euro area needs solidarity mechanisms in extreme cases which are beyond national policies. Such a mechanism is the European Stability Mechanism (the eurozone's permanent bailout fund amounting to 500 billion euros).

Everything else, though, does not deserve further fiscal centralisation. Fiscal discipline starts at home. What can be done at European level is to provide guidelines to governments for the right direction. Economic adjustments is best to be realised through flexible markets. Fiscal centralisation can be discussed only when the eurozone countries, big and small, have put their houses in order fiscally, financially and economically. That is why, the French member of the executive board of the ECB said, "our common future cannot be found in the past".

A semi European, semi national resolution mechanism

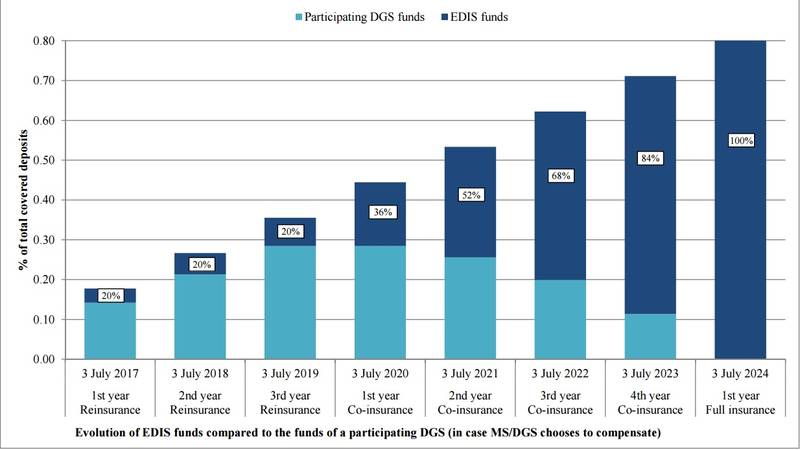

Precisely in the spirit of what Mr Benoît Cœuré said was the many hours long marathon in the economic and financial affairs council (Ecofin) on December 10th in Brussels. The ministers discussed three interconnected and very complex legislative proposals. One is the bank resolution and recovery directive (BRRD). The second is the deposit guarantee scheme (DGS) directive and the third is the single resolution mechanism (SRM). If during the weekend statements by key finance ministers  (Germany and France) suggested that already available are all conditions to reach an agreement on the second pillar of the banking union, on Tuesday morning the moods were rather pessimistic.

(Germany and France) suggested that already available are all conditions to reach an agreement on the second pillar of the banking union, on Tuesday morning the moods were rather pessimistic.

Swedish finance minister Anders Borg admitted that there was a risk not to be achieved a solution that would really help the economic recovery. This should be interpreted as a non-centralised solution with the Commission taking part as a somewhat centralising element. He said he expected a long night and even a second meeting, but he hardly expected that the night would continue with oral exchanges with Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem. During the negotiations there were two public discussions. The first was planned for a little after 10 o'clock in the morning CET, but was two hours late, which confirmed the expectations for a long Tuesday. And although many specific positions were expressed during the first public debate, webcast live, it was evident that the ministers were keeping the trump cards for the moment when the cameras would be switched off.

The second thing that was really interesting was the massively expressed desire not only on behalf of the Commission and the presidency, but by individual ministers as well, such a position to be hammered out that would be acceptable for the European Parliament. Something which Dutch Finance Minister and Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem disagreed with, defending a tougher course to the European Parliament saying that many of the main elements have been agreed and the space for manoeuvre to agree with the Parliament was too small. He expressed very serious objections against the attempts of reopening negotiations on already agreed back in June things, like for instance the hierarchy for bail-in. According to Dijsselbloem, if the outcome from the negotiations with the European Parliament were weakening of many of the strict rules for level playing field and solution to the too-big-to-fail problem, then hardly an agreement will be reached on the single resolution mechanism for banks (SRM).

And although many of the issues that were debated in the morning found a compromise and the presidency got a new mandate to negotiate with the European Parliament, it is already clear where the friction will be. The key word is "intergovernmental". It was clear in the morning that things were going into that direction after Wolfgang Schäuble, the German finance minister, recalled it was better the discussion to stick to the mandate given by the heads of state or government which was first to agree on the BRRD and the DGS directive and at a later stage to agree on the mechanism for bank resolution,  which will then be "aligned" with the BRRD. This practically means looking for an "external" solution. Germany until recently refused to agree on the SRM because it believed it had no legal basis.

which will then be "aligned" with the BRRD. This practically means looking for an "external" solution. Germany until recently refused to agree on the SRM because it believed it had no legal basis.

But the European institutions and many member states believe Article 114 of the Treaty gives sufficient grounds for the establishment of such a mechanism. According to Berlin, however, this does not include establishing a common fund. During the weekend, though, Mr Schäuble signalled he was ready to a compromise, but only on Tuesday night it became clear what the price was - an intergovernmental agreement or, rather, a hybrid between an the intergovernmental and community approach. According to a draft that leaked to The Financial Times, at a community level, in the form of a regulation, will be established the mechanism, its executive board, the fund, the decision-making mechanism, main principles of the banking levy that will fill the fund, and the bail-in rules. Through an intergovernmental approach will be solved the issues with the use of the single resolution fund, the clauses for compensations of non-member countries, transfers from national resolution funds to the common one and other issues.

The way things look at this stage, to an intergovernmental agreement will be left the relations with countries that are outside the euro area. Internal Market Commissioner Michel Barnier expressed significant doubts the European Parliament would accept this. Surprisingly, though, a political agreement was struck with Parliament on the next day. Still the technical details remain to be agreed in a trialogue. From the discussions that took place in the Council, it becomes clear that another option is really impossible because the issues that unite the euro and non-euro area countries are a few. The Czech Republic said it was against the so called government stabilisation tools and insisted the decision to merge the resolution and the DGS fund should be taken at national level. Also raised was the question who should take the decision that there is an extreme emergency situation or a systemic crisis. Jeroen Dijsselbloem is of the opinion, however, that if these decisions were left at national level this would spoil the whole idea. During the second public debate at 11.00 in the evening he pointed out that if things were left to the member states then every bank with problems would be of systemic risk.

The Dutch minister believes that it should be explicitly mentioned that the Commission is the one that can assess whether there is an extreme emergency situation or a systemic crisis. Anders Borg, too, said that to leave the Council to take such a decision brings additional complexity to an already too complex a system. Bulgaria's Finance Minister Petar Chobanov also said it was not a good idea the Council to decide whether there is an emergency situation. According to him, such a decision must be taken by a national body. He presented a very detailed position which outlines some concerns mainly related to the peculiarities of the banking market. A huge concern for Bulgaria is the restriction to use only up to 5% of the available funds in the national resolution fund. This is too restrictive for countries  that are not members of the SRM and which have no access to the common fund. The Bulgarian delegation distributed a new text that would allow to use sums that exceed the five per cent threshold.

that are not members of the SRM and which have no access to the common fund. The Bulgarian delegation distributed a new text that would allow to use sums that exceed the five per cent threshold.

Sofia is also worried about possible negative effects for the financial stability of countries where the financial structure of the banks is based mainly on core deposits and where the financial markets are underdeveloped, just like Bulgaria. And if there is progress in terms of the details of the BRRD, the situation with the SRM remains as complicated. The reason is, as Lithuania's Finance Minister Rimantas Sadzius explained, that the directive applies for all the 28 member states of the EU, while the SRM will cover only the euro area countries and those who join it. The ministers agreed to meet again next Wednesday when they left the most difficult and subtle details to agree on, like the issue about the distribution of votes in the executive board of the fund, its governance, the weight of votes, the fund's capital and the stages for filling it with money.

Commissioner Barnier explained that never before in the European history were three so complex texts discussed simultaneously. Almost entirely agreed is the scope of the mechanism, but the details are left to be hammered out, the Lithuanian minister added and quite broadly explained why was the intergovernmental approach chosen. "Now we have elaborated a a scheme that will not cause problems for all member states. All member states seem to be quite comfortable with. Intergovernmental agreement is one of the key elements in this scheme and there the setup of the SRF will be mainly described". What share will the intergovernmental approach have in the mechanism and the fund will depend entirely on how will the negotiations with the European Parliament go on.

Elke Koenig | © European Commission

Elke Koenig | © European Commission | © European Commission

| © European Commission | © European Parliament

| © European Parliament