Another Brick in the Banking Union's Wall

Adelina Marini, July 12, 2013

Yet in December it was clear that the member states, and most of all Germany, are not dying to deepen the European integration mainly due to the lack of a clearly expressed consensus on how should the painful measures be applied. The constantly rolling story of Greece which, as it seems, will be joined by Portugal, creates the feeling that whatever is done to recover the European economy, which more and more resembles Swiss cheese (tasty, but with a lot of holes), it will be rejected as being very painful, without proposing an alternative. Currently, the visions about the future of the euro area are divided into two groups. One, gathering together most of the nordic member states and UK, is of the opinion that it is good to have deepening of integration, but it should be done gradually after a full scaled preparation. The second group covers most of the southern European countries and is led by the Commission and Parliament. They do not want to waste any time and the integration should happen following the principle - let's do something now, but if it does not work we will change it later.

Yet in December it was clear that the member states, and most of all Germany, are not dying to deepen the European integration mainly due to the lack of a clearly expressed consensus on how should the painful measures be applied. The constantly rolling story of Greece which, as it seems, will be joined by Portugal, creates the feeling that whatever is done to recover the European economy, which more and more resembles Swiss cheese (tasty, but with a lot of holes), it will be rejected as being very painful, without proposing an alternative. Currently, the visions about the future of the euro area are divided into two groups. One, gathering together most of the nordic member states and UK, is of the opinion that it is good to have deepening of integration, but it should be done gradually after a full scaled preparation. The second group covers most of the southern European countries and is led by the Commission and Parliament. They do not want to waste any time and the integration should happen following the principle - let's do something now, but if it does not work we will change it later.

The common thing between the two groups is that they are both facing elections. The European elections, which Parliament and Commission are especially interested in, will take place in May next year, and this autumn there will be key elections in Germany.

The division between the two groups could be seen very clearly during the presentation of the second very important element of the construction of the banking union which the EU leaders agreed to in June last year - the single resolution mechanism (SRM) which is in a package with a directive for resolution and recovery of credit institutions and investment firms. This legislative package adds to the already agreed single supervisory mechanism for the banks on which, too, there was a lot of controversy, but it was relatively quickly approved. The timeline of the resolution package is the end of the current European term - the spring of next year. Taking into account the upcoming two months of summer break and elections in the end of September in Germany, sticking to this deadline seems hard.

Who should take the decision for resolution of troubled banks?

This is the question that causes the biggest controversy around the proposal, presented on July 10th by EU Internal Market Commissioner Michel Barnier. It envisages the following procedure for resolution of a credit institution:

- The ECB, as the supervisor, would signal when a bank in the euro area or established in a Member State participating in the Banking Union was in severe financial difficulties and needed to be resolved;

- The Single Resolution Board, consisting of representatives of ECB, the Commission and the relevant national authorities, to prepare the resolution;

- On the basis of a recommendation of the board, the Commission makes a decision whether and when to put an institution in a resolution regime;

- The board supervises how the implementation of the resolution programme is taking place;

- A single resolution fund will be established under the control of the resolution board which will support  financially the resolution of the troubled financial institution to avoid the participation of taxpayers, which was the main aim of the creation of the banking union.

financially the resolution of the troubled financial institution to avoid the participation of taxpayers, which was the main aim of the creation of the banking union.

Germany objects precisely this that the Commission will take the decision to start a resolution procedure instead of the member states. But Brussels believes that, unlike a "mere network of national resolution authorities", SRM with a strong centralised decision-making body and with the help of a single resolution fund would be of key benefit for the member states, the taxpayers, the banks and the financial and economic stability in the entire EU. The Commission's argument is that a strong centralised body would make sure that the decisions are taken quickly and efficiently, avoiding uncoordinated actions, reducing the negative impacts for the financial stability and limiting the need of financial assistance. Every time is the Cyprus case is quoted.

The Commission also believes that it is more appropriate to take the role than the ECB because the bank would be in a conflict with its supervisory function. Something which the Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem agrees with, although in general he opposes giving so much powers to the Commission. The EU executive advertises itself as the most appropriate institution pointing out that it has the necessary experience, it played that role for quite some time during the financial crisis. Besides, as a guardian of the treaties, the Commission is most appropriate among the other European institutions to ensure that the final decisions would be entirely in line with the principles of functioning of the EU.

Germany's strongest argument against is that the Commission has no legal grounds to get such powers. To this the Commission again responds by recalling that it is a guardian of the treaties, suggesting that no one else except it knows the treaties better. Commissioner Barnier pointed out during the presentation of the package that the proposal was consulted with the Commission legal service and is entirely covered by Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU). That article, generally speaking, gives the Commission and the Parliament the powers to undertake measures aimed at creating and functioning of the single market. Moreover, Brussels believes, that the composition of the single resolution board will take into account the interests of all member states.

A directive or a regulation for bank resolution?

What is curious here is that there are two separate legal acts. The Commission proposal from July 10th is a regulation, meaning it directly enters national legislation, and a directive which has to be transposed into national legislation. The Commission claims that both documents supplement each other, but from their content it becomes clear that this is another axis of conflict. Work on the directive is still in a very early stage. On June 27th the EU finance ministers have agreed on the mandate for negotiations with the European Parliament with the ambition the draft legislation to be approved at first reading before the end of the year. The directive aims to provide the national authorities with "common powers and instruments" to prevent bank crises and to resolve financial institutions whilst preserving the main bank operations and reduce the taxpayers' exposure to losses.

The measures the Council wants to be included in the negotiations mandate are sale of the business or part of it; creation of a bridge institution (a temporary transfer of "good" bank assets to a publicly controlled body as Slovenia did recently); assets separation; bail-in measures (the imposition of losses, with an order of seniority, on shareholders and unsecured creditors). The latter option was used for the first time in Cyprus. According to the Ecofin visions, the deposits of natural persons and micro, small and medium-sized enterprises as well as the liabilities of the European Investment Bank will be with a priority to the claims of ordinary uncovered creditors and depositors from large corporations. The  covered deposits below 100 thousand euros will be covered by a deposit guarantee scheme, is the opinion of the ministers.

covered deposits below 100 thousand euros will be covered by a deposit guarantee scheme, is the opinion of the ministers.

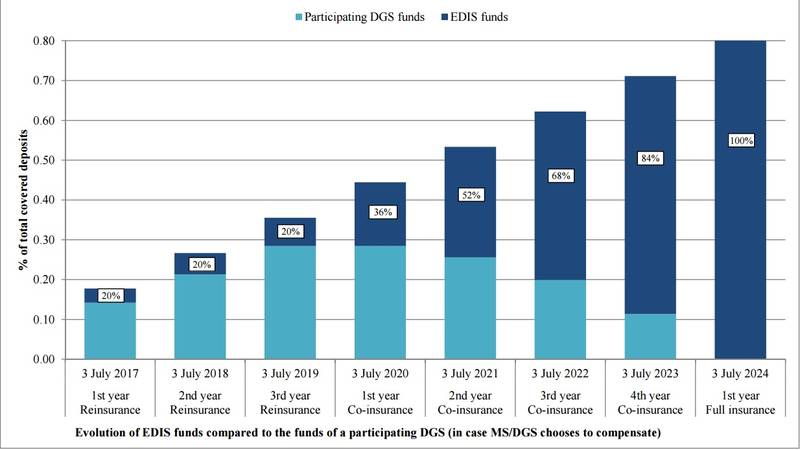

Their vision is that the member states should create their own national resolution funds where they will collect money in the course of ten years. The ceiling of the fund should be 0.8% of all the covered deposits in all the institutions licensed in a member state. For the purpose each institution will pay contributions defined on the basis of its liabilities. If a country already has a fund (Poland for instance), it will not be obliged to create a new one, but should ensure that its funding capabilities would correspond to the same amount. That vision is in contrast with the position of the Commission which believes that it is necessary to establish a single common fund whose size should be equal to 1% of the covered deposits in all banks in the participant countries. In absolute numbers, based on data from 2011, the sum is 55 billion euros.

The Commission also envisages the fund to be filled up in 10 years, but says that the deadline could be expanded to 14 years, acknowledging in the same time that public money could still be used. In its proposal, Brussels explicitly points out that the member states that already have national funds would have the freedom to decide how to use the money there until the legislation is enforced.

The Commission claims that the directive and the regulation will supplement each other, but underscores that the negotiations on the directive have not started yet. Brussels insures itself saying that it is not trying to express a preference to one of the two texts, but that it expects the differences to be cleared up in the process of negotiations and to be reflected in the final agreement on the directive. This, however, does not provide sufficient clarity why is the regulation needed since the directive is quite detailed.

Without funding from the MFF and the ESM

In its proposal, the Commission firmly rejects the possibility the costs for the work of the single resolution board to be paid from the common European budget (MFF) or by the member states. The money for the costs will be collected from bank levies which will be different from the contributions of the credit institutions to the resolution fund. Also ruled out, but not that explicitly, is the option the permanent eurozone bailout fund (ESM) to be involved in the resolution scheme, which has much more money - 500 billion euros. According to data by Commissioner Barnier, the costs will cover some 300 people in the initial stage. He was quick to compare with a similar institution in USA where 1500 people are employed.

Hitherto, the reactions to the Commission proposal are entirely with address in Berlin. The Europarliament at this stage supports anything as long as it is quickly adopted, although it will become clear in the autumn what the position of the institution will be. It is not impossible Strasbourg to demand to be involved with some form of democratic control over the new institutions. On behalf of the biggest political group in Strasbourg (EPP) Jean-Paul Gauzès (France) welcomed the proposal calling it "courageous". "The European Commission is continuing its long-lasting work on the construction of a Banking Union. This is a very good thing", the MEP added. Hannes Swoboda (Austria), leader of the group of Socialists and Democrats, also is of the opinion the news is good and pointed out that "a  resolution framework with a single resolution fund for the banks is one of the masterpieces of a future banking union".

resolution framework with a single resolution fund for the banks is one of the masterpieces of a future banking union".

Guy Verhofstadt, the chief of the liberal group (Belgium), called on the Council not to waste time and to work quickly on adopting the legislative package. He added that the legal arguments of Wolfgang Schäuble (the German finance minister) should not be allowed to slow down the quick agreement and implementation of the framework. "We no longer have the luxury of waiting for a major Treaty revision. We must all get behind these proposals now, before we are hit by another collapse of a major bank", the former Belgian prime minister appealed.

On behalf of the Greens and the European Free Alliance, Sven Giegold (Germany) pointed out that Germany has still not found allies in support of its legal argument. "The German government is putting the common efforts to establish a European banking union at risk by using spurious legal arguments. This is irresponsible because effective banking resolution is a vital part of the banking union which is a vitally important tool to face the European crisis. Further delays will increase poverty and unemployment in Europe", Mr Giegold believes.

Poland's daily Rzeczpospolita, believes however, that the envisaged size of the fund is too small. "If it comes to a crisis on the scale of the one that began in 2008 this would be no more than a drop in the ocean", the newspaper writes, quoted by eurotopics. But money is the biggest problem against the backdrop of the growing more frequent forecasts that it could come to a third bailout for Greece, which means more money, and a second one for Portugal. It is money that is in the foundation of Germany's resistance the decision about resolution of a failing bank to be taken by a centralised body which could lead to a conflict with the German Constitutional Court. This second element of the construction of the banking union is, indeed, a tipping point for the architecture of the eurozone and the EU at large and it is to dominate the new political season from the first days of autumn.

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU Elke Koenig | © European Commission

Elke Koenig | © European Commission | © European Commission

| © European Commission | © European Parliament

| © European Parliament