An Italian Remake of the Series "The Economy or Democracy, Voter"

Adelina Marini, June 7, 2018

Do you remember the beginning of 2015, when Greece was just about to exit the recession after painful and tormentous reforms? At the time, the anti-establishment party SYRIZA won the elections on a promise to re-negotiate the Greek bailout programme and to deliver debt write-off. That year will be remembered in the history of the euro area crisis with a single name - Yanis Varoufakis. He was the first minister of finance of Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, who declared war to the entire eurozone and lost it which is why he was later replaced but the incomparably more modest Euclid Tsakalotos. Three years later, Varoufakis's spirit has returned to the euro area in a very symbolic moment - right when Greece is on its way out of its third bailout programme, brought back to the establishment and looking completely tame. For now.

Do you remember the beginning of 2015, when Greece was just about to exit the recession after painful and tormentous reforms? At the time, the anti-establishment party SYRIZA won the elections on a promise to re-negotiate the Greek bailout programme and to deliver debt write-off. That year will be remembered in the history of the euro area crisis with a single name - Yanis Varoufakis. He was the first minister of finance of Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, who declared war to the entire eurozone and lost it which is why he was later replaced but the incomparably more modest Euclid Tsakalotos. Three years later, Varoufakis's spirit has returned to the euro area in a very symbolic moment - right when Greece is on its way out of its third bailout programme, brought back to the establishment and looking completely tame. For now.

Varoufakis2

The March 4 elections in Italy surprisingly did not scare neither the euro area nor the financial markets which, at that cold winter moment, seemed calm because of the ECB's hesitation when is the right time to switch the money-printing machine off and return salvation back in the hands of the member states. Less than three months after the Italian election, at which votes were shared among populist and eurosceptic parties, the form of the next rulers in the Chigi palace started to emerge*. After prolonged coalition negotiations the populist Five Star Movement of Luigi Di Maio and the eurosceptic League of ex-MEP Matteo Salvini stroke a deal which started to cause concerns in Brussels.

In their coalition agreement the two parties commit to abolish the pension reform introduced by Mario Monti's technocratic government, to increase social welfare and public spending. What started troubling the euro area's sleep, however, was the Trumpian statement "Italy first". The programme talks of "a new role of Italy in the EU which puts the protection of national interests first". This is something Matteo Salvini has dreamt of for a long time. He is a close friend of Marine Le Pen and is fond of Viktor Orban. During his rare statements in the European Parliament plenary in Strasbourg, he often spoke against the euro and the European political and financial elite.

Despite the potential danger, the coalition agreement did not cause panic in the euro area until the list of ministers was revealed. One name started circling around the Brussels corridors causing fear. This was Paolo Savona. His image has nothing to do with Yanis Varoufakis's rebellious type, who was famous with his bike, a leather jacket, and who appeared at the sleepless meetings of the Eurogroup in a shirt without a tie. When it comes to looks Paolo Savona is a complete opposite to the eccentric former minister of finance of Greece. The 81 year-old Savona always wears a costume and a tie, he wears also glasses and causes respect. He is not a novice to governance - he worked in the Italian central bank, he was a minister, a university professor and an economic expert.

The problem is, however, that when it comes to the euro his views make him a Varoufakis2. Paolo Savona is notorious with his view that Italy's participation in the common European currency was a mistake. He sees the euro area as a German diktat and believes that it is harmful for the anaemic Italian economy. The efforts of Giuseppe Conti, nominated for prime minister, to mitigate the Savona effect by saying when presenting the list of ministers that Italy intends to stick to the European rules did not bring much comfort in the other 18 euro area members.

National vs European democracy. Round two

The big question that dominated the May Eurogroup was whether Italy would be the next Greece. Some expressed openly concern, others were more cautious, and a third group insisted on awaiting the formation of a government and only then to judge it by its actions. The markets, however, started getting nervous as the spreads between the Italian government bonds and the German Bund started to expand with a pace known from the crisis times. Most direct was, as usually, Malta's Finance Minister Edward Scicluna, who said that this is disruptive policy.

The big question that dominated the May Eurogroup was whether Italy would be the next Greece. Some expressed openly concern, others were more cautious, and a third group insisted on awaiting the formation of a government and only then to judge it by its actions. The markets, however, started getting nervous as the spreads between the Italian government bonds and the German Bund started to expand with a pace known from the crisis times. Most direct was, as usually, Malta's Finance Minister Edward Scicluna, who said that this is disruptive policy.

"Overall it will do some good to the EU and the establishment because a lot of searching questions will be asked - why is the whole this anger on behalf of the peoples in some countries. However, depending on who the disruptor is, whether they have concrete proposals really to reform and get growth going, which is the remedy is growth. If, however, it's just a question of just spending and spending, borrowing and spending, unfortunately, it will be a replay of Greece and so on", were Edward Scicluna's words before the beginning of the May meeting of the euro area finance ministers, during which they discussed Greece's exit from the bailout.

His colleague from Finland, Petteri Orpo, admitted that he is worried. "I'm looking very carefully at what is happening in Italy. And, of course, I'm a little bit worried but, in the same time, I want to trust that Italians can do good solutions and they are responsible for [the] whole eurozone because they are part of the eurozone". Ireland's Minister of Finance Paschal Donohoe conveyed a diplomatic message to Rome recalling that the euro area is entering its 20th quarter of economic growth, the lowest unemployment rate since 2008, and the member states have significantly improved finances and have surpluses. "So, with that in mind, I will be looking forward to working with the new Italian finance minister but it is important that all member states and all member states' governments are aware of the responsibilities that we have to each other and to the single currency".

Paschal Donohoe stressed that Ireland is a small open economy whose interests are directly dependent on euro area's stability and growth. Ireland was forced during the crisis to request a bailout under markets pressure. It was the first country to exit its programme - successfully and quickly after implementing painful reforms. Dutch Finance Minister Wopke Hoekstra was among the cautious. He called to await the new government to take over and then to judge it by its actions. Nevertheless, he did send a message to Rome: "What I wish the Italians to have is a government that creates economic growth, that manages to push through reforms and that comes up with a budget discipline. Not because that is something Brussels would like or that some other member states would like but because it is my conviction and my firm believe that is what is in the long-term interest of Italy and of the Italians".

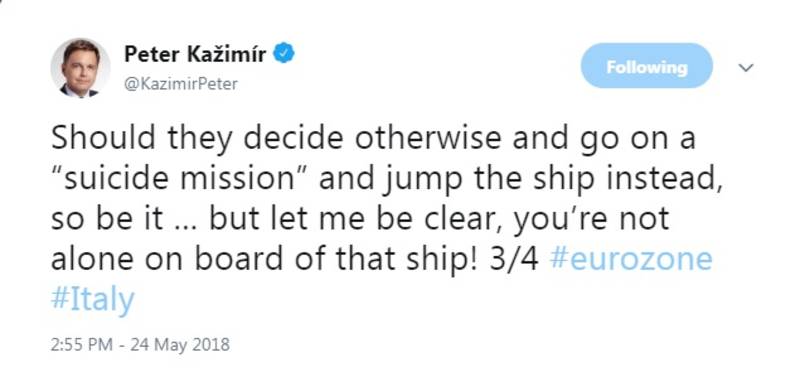

Hoekstra also said that there is a very good reason why the euro area has these specific rules. "We've agreed on them because it is the belief of all member states that these rules are of the interest of our citizens and in the interest of the long-term well-being of our citizens". The Dutch finance minister underscored that rules are something the member states have deliberately chosen, not something Brussels imposes on them. Slovakia's Finance Minister Peter Kazimir dedicated several tweets on Italy the first of which started with the words that "political situation in Italy does not keep me up all night ... for now". In a subsequent tweet he expressed hope that the new Italian government will not ignore the rules and take the euro area hostage for the sake of pre-election promises. "Should they decide otherwise and  go on a 'suicide mission' and jump the ship instead, so be it … but let me be clear, you’re not alone on board of that ship", Peter Kazimir added.

go on a 'suicide mission' and jump the ship instead, so be it … but let me be clear, you’re not alone on board of that ship", Peter Kazimir added.

The EU commissioner for economic, financial and taxation issues, Pierre Moscovici (France, S&D), called for respect for democracy in the member states. "For the time being, there is no government in Italy or there is an acting government and the Commission fully respects the democratic legitimacy of the future government, also the democratic rhythm of decisions in Italy", he said before the Eurogroup meeting on May 24. However he welcomed the statement by the then candidate for the premier position, Conti, that he wants a dialogue with Europe. Moscovici's statement before and after the meeting, as well as during the presentation of the most important package of the European semester, represented the usual search for balance. On the one hand, the commissioner was trying to send a message to the Italians, who rebelled against the status quo, that Europe will not impose anything on them and will respect their democratic choices.

On the other hand, he wanted to calm the markets as well by showing them that Brussels can handle this situation as well, saying that the Commission is ready for a "constructive dialogue" with the future Italian government and minister of finance. Moscovici also wanted to calm the disciplined member states by telling them that he is aware of the Italian problems: "[W]e have some points on which we will be attentive and I think about one specifically which is the high level of the public debt in Italy, but we will have the time to discuss that". He stressed that historically Italy is at the heart of Europe and was convinced that it will remain an important member of the currency club.

Eurogroup chief Mario Centeno (Portugal, independent) said that Italy was not discussed at the meeting but he recalled that the euro area has a well developed framework of rules. "We have been quite, quite successful at implementing it", he said. Centeno promised that the challenges for all countries will be taken into account.

A day before the Eurogroup, the Commission published the country-specific recommendations for each member state. Italy's show that the country has a lot of work to do, commensurable with the reforms Greece had to go through. In 2017, Italy's public debt dropped slightly from 132.0% to 131.8% of GDP and is expected to continue to decline. The Commission bases its expectations on Italy's reforms programme which, however, could become irrelevant after the new government takes the reins in Rome. If it is convinced to continue in the same spirit, the debt could drop to 122.0% in 2021. To compare, Greece's public debt was 178.6% of GDP in 2017. This year it is expected to fall to 177.8%, and next year to 170.3%.

One of the big problems surrounding Greece's exit is debt relief. The IMF has not yet joined Greece's bailout programme because it deems Greek public debt unsustainable which means it will continue to create problems in the future. The Fund set as a pre-condition for joining a degree of debt relief but the May Eurogroup showed that the euro area is now ready to swallow IMF's non-participation.

In the document on Italy, the Commission seems to be refuting every point of Di Maio's and Salvini's agenda. It says that spending on pensions in Italy is currently among the highest in the EU - around 15% of GDP. The Commission recalls that the pension reform, known as the Fornero Act, has already been significantly rewound in 2017 and 2018. The Commission has long criticised Italy for its taxation system, which is too complex and is focused on capital and labour which hampers economic growth. Italy is one of the countries with high level of shadow economy - around 12.9%. Investments have not yet reached pre-crisis levels, mainly due to unfavourable business environment.

The report criticises the inefficiency of the Italian judiciary and the corruption, described as "a major challenge for Italy’s business environment and public procurement". The quality of the Italian public administration is also low. Italy has problems in its banking system too, despite the improvements in recent years. The level of non-performing loans continues to be high but, according to the Commission, if the pace of reduction is maintained this will strengthen financial stability and will increase lending. The latter is related to another problem outlined by the Commission, which is low access to financing in Italy. The legacy in the banking system is also hampering the completion of the banking union in the EU.

The report criticises the inefficiency of the Italian judiciary and the corruption, described as "a major challenge for Italy’s business environment and public procurement". The quality of the Italian public administration is also low. Italy has problems in its banking system too, despite the improvements in recent years. The level of non-performing loans continues to be high but, according to the Commission, if the pace of reduction is maintained this will strengthen financial stability and will increase lending. The latter is related to another problem outlined by the Commission, which is low access to financing in Italy. The legacy in the banking system is also hampering the completion of the banking union in the EU.

Varoufakis's spirit will remain even without Savona

Literary the next day after the meeting of the finance ministers, in Italy, there was another change. President Sergio Mattarella blocked Giuseppe Conti's government precisely because of Savona. "The designation of the Minister of the Economy always constitutes an immediate message of confidence or alarm for economic and financial players", explained the president his decision. "For that Ministry, I asked for the indication of an authoritative political representative of the majority, coherent with the agenda of the political alliance. A representative who - beyond the respect and consideration that I have for the person - may not be seen as the promoter of a line of reasoning, often manifested, that could probably, or even inevitably, provoke Italy's exit from the Euro", Sergio Mattarella said.

He pointed out that uncertainty surrounding Savona's position on the common currency increased concerns among investors and savers, Italian and foreign, who invested in government bonds or in Italian companies. Savona's rejection increased fears of new elections but for now it seems that Five Stars and the League will try again to form a government [the attempt was successful]. They did not give up on Paolo Savona but there was talk he would be given another position [he was appointed European affairs minister].

Greece had a hard time learning the Varoufakis lesson but the difference with 2015 is that the euro area now has a lot of experience in playing hard games. After all, when it comes to comparing democracies, in the Eurogroup there is democracy too and the majority will have the final word. Probably, it will not come to severe jolts in the euro area but the question is what will be the price tag. The deepening of integration in the euro area will probably be put on hold. The new government in Italy adds further hardship for the ECB in forming its monetary policy. ECB President Mario Draghi (Italy) is  ready to continue the policy of QE until there is a risk for the euro area. In the past months the risks were mainly external. Now, however, a strong internal risk has emerged.

ready to continue the policy of QE until there is a risk for the euro area. In the past months the risks were mainly external. Now, however, a strong internal risk has emerged.

With the League in government, the EU is faced by another period of being carried away by the stream which, in today's tumultuous geopolitical times, is not a good news either. Unlike Greece, which was forced to listen to its lenders, Italy is still free to impose its agenda. And the scale is much bigger as Italy is the third largest economy in the euro area, which means it is too big to be saved with the euro area's available tools. Besides, disputes with Italy will not be related only to economic and fiscal policy but also to migration and foreign policy. In the coalition programme of Di Maio and Salvini it is said that they will work for removing sanctions against Russia and for a dialogue with Moscow. Problems may occur almost on all community issues.

*It took a while this text to be translated and by that time a new government led by Giuseppe Conti was formed with Di Maio and Salvini deputy prime ministers.

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU Mario Draghi | © ECB

Mario Draghi | © ECB