Banking Resolution Is Now Available in Uncertain Legal Environment

Adelina Marini, February 2, 2016

The Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) is not yet fully transposed and the different legislation in member states pose a risk to the work of the second pillar of the banking union, which is in full operation since January 1st. Those are some of the problems, laid out by Single Resolution Board Chair Elke König during her first hearing in the European Parliament’s economic committee this year. The most important task of the board for 2016 will be letting financial markets know exactly what the rules for bank resolution and recovery are, as well as the fact that they are going to be enforced, she said on January 28th. The Single Resolution Mechanism is the second pillar of the banking union, devised in 2012 with the purpose of ending the malpractice of taxpayers saving banks in trouble.

The Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) is not yet fully transposed and the different legislation in member states pose a risk to the work of the second pillar of the banking union, which is in full operation since January 1st. Those are some of the problems, laid out by Single Resolution Board Chair Elke König during her first hearing in the European Parliament’s economic committee this year. The most important task of the board for 2016 will be letting financial markets know exactly what the rules for bank resolution and recovery are, as well as the fact that they are going to be enforced, she said on January 28th. The Single Resolution Mechanism is the second pillar of the banking union, devised in 2012 with the purpose of ending the malpractice of taxpayers saving banks in trouble.

The first pillar is the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), which is implemented by the European Central Bank, and the second one is a complex structure made up of European legislation and an intergovernmental agreement, whose role is developing plans for resolution of banks in trouble and providing the financing for it. A special fund has been created for this very purpose, with combined capacity of 55 billion euro, which is expected to be filled gradually by the year 2023 using contributions from the banking sector. Until then, however, national resolution funds will be providing bridge financing to the single fund. It is expected that this year banks will pay contributions into the fund for the first time at the amount of 11.8 billion euro. The problem is that the construction of the second pillar of the banking union is too complex, as Ms Elke König admitted during her hearing.

The banking union is currently operational only in euro area countries. Parallel to it, however, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive was adopted, which applies to the whole EU. According to it, member states are obligated to accumulate money in their own funds, which are then transferred to the single fund, in addition to the contributions from banks (just for countries participating in the banking union). There are, however, differences in the way that financial institutions’ contributions are being calculated under the directive and under the single mechanism. This is why, from 2016 to 2023 there will be a transitional regime in force, under which the weight of contributions under the Directive will decline from 60% this year to 7% in 2022, and the weight under the mechanism will grow from 40% in 2016 to 93% in 2022, reaching 100% in 2023. Contributions will be determined based on the level of risk and the size of banks.

In the words of Elke König, the Single Resolution Board is still a start-up. There are 130 people working for it at the moment, who, she says, are sufficient in case of need, but it is best that such needs do not arise just yet. Manuals are supposed to be developed by the end of the year for the development of resolution plans. It is yet to be seen how the relationship between the board and the supervision will work out, which, again in the words of Ms König, is very well explained in the legislation, but realities often differ.

By the end of the year the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) are supposed to be developed as well. This is a very important element of the mechanism, for it concerns the rule for bail-in by the shareholders. The MREL formula is the loss absorption amount plus the recapitalisation amount minus the correction for guaranteed deposits. According to Elke König, for the time being the minimum benchmark of MREL will be 8% of all liabilities, but it is too early to say what percentage will it reach for the largest banks. This will be assessed separately for each bank. Credit hierarchy and subordination will be extremely important for the determination of MREL. MREL is being introduced with the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive and this is exactly why it is very important that it is transposed. In the words of Elke König four member states have yet to finalise the process, but she refused to name them. “I wasn’t really prepared for naming and shaming”. She just pleaded that this gets done as soon as possible.

Another obstacle to the work of the bank resolution mechanism, which was pointed out during the hearing, is the difference in insolvency laws. According to Elke König, it is very unlikely that these laws will be harmonised any time soon. Differing legislation frameworks emerged as a problem during the several cases of bank resolution last year, said Elke König, and later agreed that differing rules in various member states and the still excessive power of national authorities present a problem. The issue is most serious in the divergent laws regarding hierarchy of claims, which will seriously affect the implementation of the first step of bank resolution – the shareholders’ money. This is especially problematic when large trans-border banks are involved.

In a document, specially prepared for Elke König’s hearing on January 28th, the credit rating agency Moody’s is quoted that "the lack of uniform hierarchy of claims across the region adds further complexity to the resolution of banks across borders". There are complaints as well from divergent senior debt treatment, for it distorts the banking sector and makes fund raising more complex. Rabobank, however, is of the opinion that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to all problems.

Portuguese MEP Elisa Ferreira (Socialists and Democrats), who participated in the negotiations for the creation of the second pillar of the banking union, warned that there was a risk of a systemic crisis because of the lack of coherent instruments. “You can trigger a  really serious systemic crisis just because there is no full compatibility of timing and the overall approach of how things interact”.

really serious systemic crisis just because there is no full compatibility of timing and the overall approach of how things interact”.

“You’re right”, replied the Board’s boss. “I think that is something we are all aware of”, she added. The answer, in her opinion, is to take careful steps. There are two options – either funds get raised, or the size of the bank balance sheet gets reduced. “But there is no silver bullet to solve the problem”, admitted Elke König and chose to quote Mikhail Gorbachev that the later it starts, the more difficult it will be. Dutch MEP Esther DE Lange (EPP) corrected her, pulling out the exact Gorbachev quote: “Life punishes those who come too late”. Elke König believes that the creation of a financial buffer is of prime importance, for the Single Resolution Fund is to be used only as a last resort. “I hope that we never ever have to touch it, but it should be kind of sleep-well cover”, added Elke König. There is still no agreement on this among member states, however.

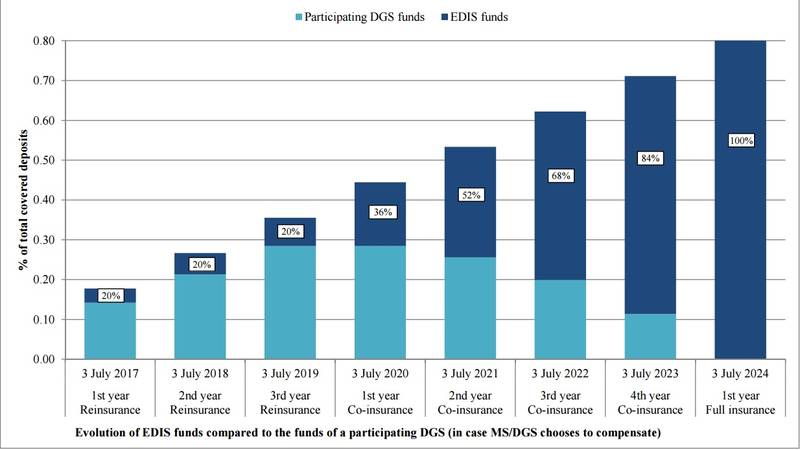

In her opinion, the third pillar of the banking union – a common deposit guarantee scheme – is also very important, but there is no agreement among member states about it either. The Commission’s proposal in this direction was met coolly by the Council. The main argument is with the states, led by Germany, which think that first of all there should be work done on lowering the risk and only then on its sharing. Others are of the opinion that the two can go in parallel.

It says in the document, written especially for the hearing, that there is improvement since 2009, when the world financial crisis erupted, regarding the weakest capital positions of banks, which fall under the direct supervision of the Single Supervisory Mechanism. If in 2009 the ten weakest banks had tier 1 capital of less than 8%, by the end of June 2015 seven out of the ten were with more than 9%. On all other indicators, however, the situation is actually deteriorating. The quality of assets of the worst-performing banks has deteriorated since 2009. This deterioration is a direct result of the sizable jump of non-performing loans in the countries that got hit the strongest by the crisis. ECB boss Mario Draghi speaks more and more often of this problem as well.

The situation with the liquidity of the worst-performing banks has also significantly deteriorated since 2009, says also in the document, drafted using publicly available data. This shows that the challenges that the second pillar of the banking union will face are going to be serious. The question is whether this complex structure mechanism will cope in case of need. Alas, Elke König’s hearing last week failed to provide a clear enough answer to this question. Moreover, doubts remain, after she stated that the mechanism is ready for work, but it is best that there comes no need to resort to it very soon.

Translated by Stanimir Stoev

| © European Commission

| © European Commission | © European Parliament

| © European Parliament | © European Commission

| © European Commission