Reforms and the Single Market Are the Future of the Euro Area

Adelina Marini, February 19, 2015

The issue because of which the informal European Council on 12 February was convened was left with no attention at all at the summit, the agenda of which was completely overtaken by the situation in Ukraine and the renewed conflict with Greece. The journalists did not pay attention to the third most important point on the agenda to such an extent that Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission chief, said half jokingly half seriously that since there was no interest then he would not tell us anything about the talks among the 28 on the issue. In fact, there was not much to tell because at this summit was presented only the "analytical note" of Mr Juncker, developed in cooperation with the other three presidents - ECB chief Mario Draghi, Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem and European Council President Donald Tusk. The note will serve as a basis of a fully fledged new report of the four presidents which will be presented to the leaders at their summit in June.

The issue because of which the informal European Council on 12 February was convened was left with no attention at all at the summit, the agenda of which was completely overtaken by the situation in Ukraine and the renewed conflict with Greece. The journalists did not pay attention to the third most important point on the agenda to such an extent that Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission chief, said half jokingly half seriously that since there was no interest then he would not tell us anything about the talks among the 28 on the issue. In fact, there was not much to tell because at this summit was presented only the "analytical note" of Mr Juncker, developed in cooperation with the other three presidents - ECB chief Mario Draghi, Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem and European Council President Donald Tusk. The note will serve as a basis of a fully fledged new report of the four presidents which will be presented to the leaders at their summit in June.

And as Jean-Claude Juncker believes that the ideas in the previous four presidents' report and the solo action of his predecessor Jose Manuel Barroso are still valid, what makes his analytical note valuable is the analysis of the crisis and all the changes made so far. According to the text, the first decade of the euro, which introduces common fiscal rules, did not lead to significant reduction of the public debts and deficits below the limits of 60% of GDP for the debt and 3% for the budget deficit. In 1998, the government debt in the euro area was on average 72.8% of GDP and was reduced to "only" 66.2% in 2007 and all this in the most favourable macro economic environment that allowed for much stronger fiscal consolidation. The deficits in the single currency block were on average 1.9% of GDP in the period 1999-2007 with a peak of 3.1% in 2003.

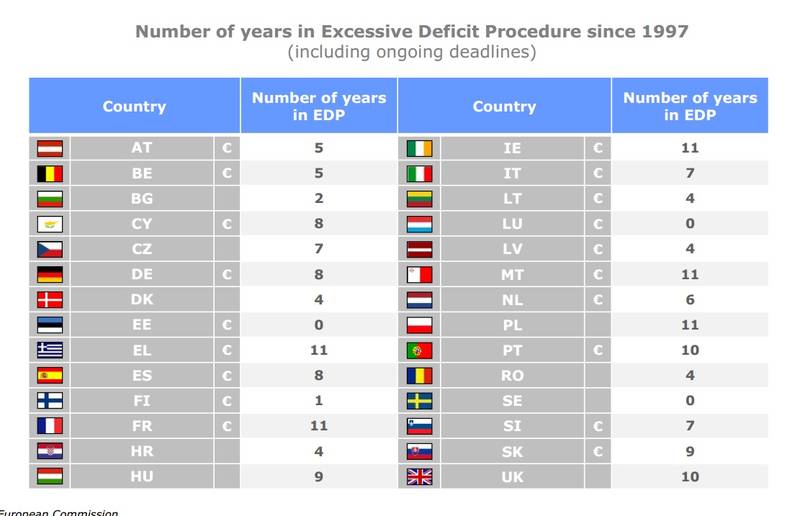

Since the inception of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) most of the euro area member states (excluding Estonia, Luxembourg and Sweden) have been at least once a subject of an excessive deficit procedure. The chart Mr Juncker presented the prime minsters and presidents with last Thursday makes it clear that most of the member states who share the euro were in the procedure for many years. Ireland, for instance, 11 years, just as France, Malta and Greece. The shortest time in the procedure spent entirely nordic economies: Lithuania, Latvia and Denmark 4 years, Finland 1 year, Belgium 5 years, The Netherlands 6 years. Against the backdrop of the weak adherence to the common fiscal rules in 2005 they were additionally weakened. As a result of the crisis, the public debts and deficits significantly bubbled in almost the entire eurozone. The average level in 2010 was 6.2% of GDP for the deficits. In 2014 they returned to normal - 2.6% of GDP. The situation with the public debt, however, continues to deteriorate. Last year, the average level was 94.3%.

The problem, however, are not only the fiscal rules but also the so called in the analytical note "competitiveness crisis". It is about low productivity in many of the euro area countries, mainly in the labour and product markets.

The document mentions also another factor for the crisis which is that the markets viewed the eurozone as a whole and not as separate economies with divergent levels of risk. A "mistake" that is being made today as well. This was the main reason for the domino effect in the beginning of the crisis. And as the situation in the euro area continues to be fragile, mainly due to problems in individual member states, Jean-Claude Juncker is of the opinion that the EMU needs to go gradually for "concrete mechanisms for stronger economic policy coordination, convergence and solidarity". Such mechanisms should be based on the economic, social and unemployment realities in the EMU countries, the economic interconnectedness and the convergence capacity.

The document mentions also another factor for the crisis which is that the markets viewed the eurozone as a whole and not as separate economies with divergent levels of risk. A "mistake" that is being made today as well. This was the main reason for the domino effect in the beginning of the crisis. And as the situation in the euro area continues to be fragile, mainly due to problems in individual member states, Jean-Claude Juncker is of the opinion that the EMU needs to go gradually for "concrete mechanisms for stronger economic policy coordination, convergence and solidarity". Such mechanisms should be based on the economic, social and unemployment realities in the EMU countries, the economic interconnectedness and the convergence capacity.

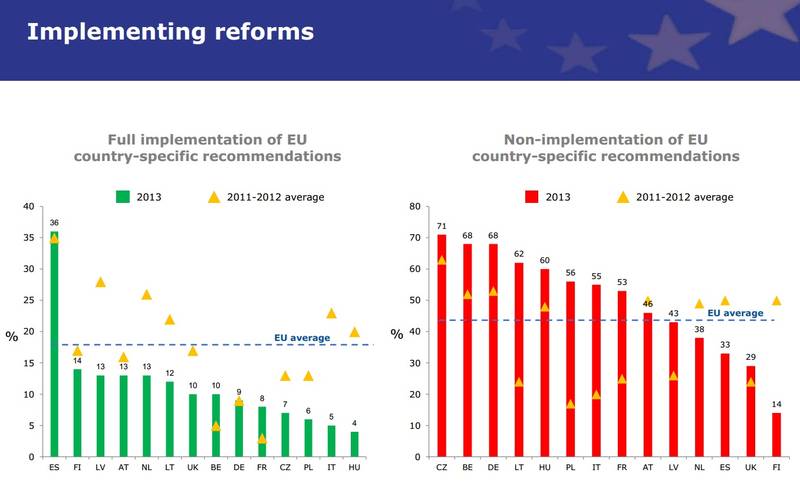

In other words, what Juncker wants and is a major slogan of his Commission is the member states to bind themselves much stronger to their commitments. In the short term, he writes, it is important to adopt a strategy around the "virtuous triangle" of structural reforms, investments and fiscal responsibility. The implementation of commitments made by all euro area countries is not satisfactory. In support of his claim Juncker presented a chart showing that the implementation of measures is very low. A renewed political consensus is needed to implement the necessary structural reforms "with decisiveness". As Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis explained after the meeting of the EU finance ministers on Tuesday, if all European countries, including the biggest ones, implement significant reforms without hesitation the growth in Europe would be much faster and sustainable.

"The external circumstances, such as the geopolitical tension, should not become an excuse not to do our homework", he said and recalled that there already is a proof that reforms work. "The countries that have reformed themselves, like Ireland, Spain, the Baltic nations, including Latvia [which he was until recently a prime minister of] are again growing. Reforms are working also in Portugal", Mr Dombrovskis added.

In addition to the structural reforms, the Commission insists on improvement of the functioning of the single market. An issue which was raised many times during EU summits in the period of the crisis but, again, to no avail at national level. Junker's analytical note focuses on labour mobility, the completion of the banking union, the creation of a capital markets union, an energy union and the digital economy. According to him, if there is progress on these points, it is very likely the functioning of the  euro area to be improved significantly in the coming 18 months. The only thing that is needed is political support.

euro area to be improved significantly in the coming 18 months. The only thing that is needed is political support.

Regarding the long-term plan, Jean-Claude Juncker entirely backs the two previous documents - the four presidents' report and Jose Manuel Barroso's vision. Although they are similar, still, there are some important differences, so it would be interesting to see what part of them will find a place in the second report of the four presidents in June. In the first report, prepared under the leadership of Herman Van Rompuy, the ex-chief of the European Council, was envisaged contractual agreements for structural reforms to be concluded between the member states and the European institutions. Those agreements were to replace the current adjustment programmes invented to save Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Cyprus from default. The report also envisaged the financial assistance to come from the multiannual budget of the EU. The third phase of Rompuy's report envisaged also the creation in the future of a separate budget of the euro area to "absorb shocks", which will be directly linked to the contractual agreements for reforms.

Unlike that report, in Barroso's vision there were several other quite integrationist measures, some of which require treaty change. One is a reform of the six-pack to include a "convergence and competitiveness instrument" the purpose of which would be to make targeted investments in economic convergence. This instrument will be in fact a package of reforms and commitments bound to specific deadlines the aim of which is precisely to catch up with the best performing economies. Barroso proposed the instrument to be funded by a "fiscal capacity" - something like a euro area budget but not exactly. The former prime minister of Portugal also proposed deepening of the coordination of tax policies and labour legislation. Among his ideas was also the creation of eurobills.

Unlike the period when Barroso's ideas and those of the other three presidents (some of whom will participate in the current configuration as well) today's environment is not at all a breeding ground for integrationist views, especially after the renewed infection of the Greek problem. That is why, it is very likely the leaders to focus on the short-term goal Juncker, Draghi, Dijsselbloem and Tusk offer and which is structural reforms and improvement of the investment climate. If that delivers the desired result, then it is possible the appetite for discussing ideas about the future to be restored. Something the German finance minister, Wolfgang Scheuble, said directly during one of the discussions recently of the reform of  the economic governance of the EU and the euro area - more integration yes, but not when the existing rules are not adhered to.

the economic governance of the EU and the euro area - more integration yes, but not when the existing rules are not adhered to.

In this sense, Greece holds the key because around the renewed crisis over the source of the domino effect in the euro area, the respect for the rules united many of the member states, even France - one of the countries with the weakest implementation on national level of commitments made at European level.

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU Boyko Borissov | © euinside

Boyko Borissov | © euinside Angela Merkel, Vladimir Putin, Francois Hollande | © Bundesregierung

Angela Merkel, Vladimir Putin, Francois Hollande | © Bundesregierung