David Cameron's Mission Impossible

Adelina Marini, April 3, 2015

The spring European Council was the last for David Cameron before the 7 May general election in Britain. Probably, many in Brussels will breathe a sigh of relief if he lost the election, as he himself suggested in front of journalists in the end of the second day of the summit but, in fact, although a pain in the heel, if Cameron lost this could mean a loss for the EU too - of a strong example for successful economic recovery against the backdrop of the useless several-years-long disputes for or against austerity (the policy of tight fiscal discipline). Certainly, a possible victory of the Labour under the leadership of Ed Miliband would not bring that peace everyone is dreaming about on the continent because the gin has long been out of the bottle and it is more likely an in-out referendum to take place than not to. Therefore, the election on 7 May will be a general rehearsal for the referendum on Britain's EU future.

The spring European Council was the last for David Cameron before the 7 May general election in Britain. Probably, many in Brussels will breathe a sigh of relief if he lost the election, as he himself suggested in front of journalists in the end of the second day of the summit but, in fact, although a pain in the heel, if Cameron lost this could mean a loss for the EU too - of a strong example for successful economic recovery against the backdrop of the useless several-years-long disputes for or against austerity (the policy of tight fiscal discipline). Certainly, a possible victory of the Labour under the leadership of Ed Miliband would not bring that peace everyone is dreaming about on the continent because the gin has long been out of the bottle and it is more likely an in-out referendum to take place than not to. Therefore, the election on 7 May will be a general rehearsal for the referendum on Britain's EU future.

For the first time since the "special" relations of the United Kingdom with the European Union European issues are not just part of the election campaign but are leading topics. This is a precedent and is a result of David Cameron's efforts to play a difficult political poker with an unequal opponent - the populist and eurosceptic Nigel Farage. A poker in which he involved the completely unprepared for such a game EU. In the past 3 years, each EU summit was a real test for the nerve system of the most influential leaders in the Union, especially Chancellor Angela Merkel to whom David Cameron is much more than just a small stone that hurts in her shoe. And the problem is not that the British premier is not right in principle. The problem is that he is moved by a narrow national interest, whereas to Angela Merkel a priority is the common European interest because it is a national one to Germany.

This is exactly the mistake David Cameron has been making every time when he speaks about a reform of the EU - he always bends this through the British national interest without binding that interest to the EU in any way. To Britain, the developments on the continent are foreign policy and that is why during his first public event as part of the election campaign he spoke of his achievements at European level in terms of foreign policy successes. But to the members of the euro area, everything that is happening in EU is part of their national interest because they share a common currency. It is slightly different with the non-euro countries but they are dominated by countries for which the membership in the EU is a geo-strategic and civilisational choice. In this sense, UK is alone, although it has partial allies, mainly in the nordic part of Europe.

Eurozone is impeding Britain's development

The thesis has been stated a number of times by the British prime minister since the very beginning of the debt crisis in the euro area. However, this is one of the many misleading theses of the conservative leader because Britain is not part of the currency block and that is of great importance for the final outcome. Nonetheless, there is no way the success of the British economy to be ignored. In 2014 it scored solid economic growth of 2.6% and the expectations for the expansion of the gross domestic product this year have been revised upward on 31 March. To compare, the growth of the British economy in 2013 was 1.7%. Currently, the economy of the UK is among the fastest growing economies in the entire EU, alongside the Baltic states (Lithuania 3%, Latvia 2.6%), Ireland (4.8% in 2014), Romania (3.0% in 2014) and Poland (3.3% in 2014). Generally, the economies that grow the most at the moment in the EU are the new member states. Unemployment in Britain has also declined from 7.6% in 2013 to 6.3% last year and it is expected to continue to decline.

During his five-year long mandate Cameron's government has cut the country's budget deficit in half - from 10.8% in 2009-2010 to 5.4% in 2014-2015. According to the European Commission forecast, the deficit is expected to decline to 3.6% in 2016-2017. Because of the budget gap and the problems in the housing market Britain is among the 16 member states included in the macroeconomic imbalances procedure, although it is still at the lowest alert level - second level, which requires monitoring and policy action. Last year Bulgaria was at that alert level but is currently at the level before last - number five - along with France, Italy, Portugal and Croatia. On the second level together with UK are also the Netherlands, Belgium, Romania, Finland and Sweden.

The government of the Tories and the LibDems is generally led by its own views about the economic development and often rejected the "interference" of the European Commission. This can be seen in the country's results in terms of implementation of the country-specific recommendations - in the past year "limited" progress has been achieved. This is the Commission euphemism for complete non-implementation. And what the Commission recommends, but is perceived as interference (not only by London for that matter), is to broaden the tax base, fiscal consolidation to continue (because of the still high budget deficit), upgrading the infrastructure and, most of all, solving the problem with housing where the Commission sees the potential of a new bubble.

To David Cameron, however, there is no problem as long as the economy is growing. He sees a strong contrast between the euro area and the way in which the British economy is going out of the crisis. "We've created more jobs in the UK than the rest of Europe put together. Indeed, Yorkshire has created more jobs than the whole of France", the British premier boasted in the afternoon of March 20.

From austerity to prosperity

In The Sunday Times after the summit David Cameron published an article in which he threatened that if Labour won the election the country would become as bad as France. And during the EU summit in Brussels he recalled that before the Tories took over in 2010 the UK budget deficit was as big as Greece's. Five years later, though, there are again parallels between Greece and UK. While the Greek populist prime minster, Alexis Tsipras, is draining the last drops of the euro area's solidarity and understanding claiming he has been empowered to demand renegotiation of all agreements with the Greek lenders by a clear mandate of the people, in the other end of the EU David Cameron also talks about a strong mandate.

"If I come back here [Brussels] after the next election I will have a mandate. And a mandate to deliver change in Europe". He was confident that a possible mandate would be taken seriously and that the demanded change is achievable. The British premier refused, however, to be compared to Tsipras. "The Greek situation is totally different. We're not part of the eurozone. We've not made a whole set of promises about our economy and we're not trying to borrow money off anybody, indeed". But the feeling of a more refined Tsipras is haunting Brussels because Cameron has indeed made a promise for changes in the EU even before he had discussed this with his European partners. When it comes to the budget deficit, however, both cases are excessive. Therefore, it is hard to talk about austerity. Rather it  would be more correct to talk about adjustments. It is a fact that during Cameron's government the economy has restored its growth but it is also true that its public debt continues to grow.

would be more correct to talk about adjustments. It is a fact that during Cameron's government the economy has restored its growth but it is also true that its public debt continues to grow.

In the budget year 2013-2014 the size of the debt was 87.8% of GDP and is expected in 2016-2017 to reach 90.5% of GDP. The Commission forecast is that the debt-to-GDP ratio will reach 102.7% by 2025. According to Cameron, though, all problems can be resolved if the economy is growing. And for now this is the only trump card he has in his sleeves. This trump card, however, is very strong in a combination with the euro area member states like Ireland and the Baltic states which have restored their economies after painful efforts. These countries have great weight when talking to Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras. Ireland Prime Minister Enda Kenny said in the end of the EU summit that he explained in detail to his Greek counterpart what Ireland went through.

Not a Tsipras but a taller Tom Cruise

On 1 December the former prime minister of Poland, David Cameron, took over the European Council presidency from the Belgian Herman Van Rompuy with a very clear mandate given to him by the leaders of the 28 member states, including Britain, in the end of August. His task is in the next two years and a half (this is the duration of his term) to tackle the three main challenges the EU is facing: a stagnating economy, the Ukraine-Russia crisis and the place of Britain in the EU. In the end of the spring EU summit on 20 March, Donald Tusk said that Cameron's demand for a deep reform of the EU is close to a mission impossible. He used this comparison for the first time in an interview a week before but in Brussels he said he was not joking.

"In fact", he said responding to a British journalist, "mission impossible means a very difficult mission with happy end in the end". He recalled that Tom Cruise's character from the Mission Impossible movie always wins in the end. But still, the demand for changes of the EU treaties is something very similar to a mission impossible. "We have to try to find good solutions for UK under the current treaties and, of course, if it is necessary, we can discuss a mission impossible with a good will and happy end", Donald Tusk added hoping that Cameron understood him well. He did not. The British premier agreed that Tom Cruise always wins in the end and added: "He's a little bit smaller than me but I hope to be just as effective", he responded to Tusk provoked by a journalist. "I know that Donald will be helpful as chairman of the European Council to bring forward what's necessary to reform the EU. I'm confident about that".

He maintained the same confidence also during the Battle for Number 10 - the first public clash between him and his main opponent Ed Miliband on Sky Jews and Channel 4. While talking about a mandate for a change of the EU, Ed Miliband was explaining that he is against a referendum and that it is very unlikely, if elected, such a vote to take place because it is harmful to even discuss leaving the EU. This would be devastating for the British economy, the Labour leader believes. At the moment, the support for the two major parties is completely squared, which means that a key role will play the smaller parties as potential coalition partners. David Cameron leads the first coalition government in the British post-war history with a junior partner Nick Clegg's LibDems. However, there is talk about a possible alliance between the Tories and Nigel Farage's Independence Party. But the way Cameron tells one thing to his compatriots at home while Brussels is telling him something different is also a strong reminder of the problems with "translation" between Tsipras and his euro area partners.

Let's fight for Britain just like Cameron fought for Scotland's heart

No matter who will win the election on 7 May, it is very unlikely to avoid a referendum. Since the famous European speech of David Cameron three years ago the issue has been present every day, no break, in the British public domain. It is a pity that this was ignored by the rest in the EU as a purely British issue but it is not. David Cameron is right when he says that the EU is an imperfect organisation and that something needs to change. The problem is, however, that although there were attempts to avoid a two-speed Europe it is a fact. Currently work is ongoing on a new vision about the future of the euro area only. There is nothing to discuss about the rest because, according to their accession treaties, all non-euro countries (except those that have special arrangements) are obliged to accept the common currency one day. At the moment, the currency club has 19 members. Only 8 are outside.

This means that only the developments in the euro area enjoy a priority status. What can be done for Britain, however, is to negotiate something special. It is evident that the relations with the UK will never (or at least not in visible future) be the same as those among the other member states that perceive the EU as their own peaceful project. Moreover, Britain will never be as close to the EU as are the countries that share a common currency. The EU itself does not need a comprehensive reform right now. What it needs is the member states to start implementing the rules. Against this backdrop, it is very unlikely the treaties to be opened for negotiation exactly now, even if Cameron wins. If the current course of behaviour is maintained - David Cameron to brutally blackmail his partners without taking into account the peculiarities and needs of the common currency as well as the peculiarities of the Union itself as such, and on the other hand the EU to behave as if nothing important is happening on the other side of the Channel - then we are headed toward a certain British exit (brexit).

This is not a good idea exactly at a time when a possible exit of Greece is being discussed with much more comfort than before. However, Britain, despite some petty behavioural resemblances, is not Greece. Britain has always been a source of more pragmatism, free trade and was among the strongest voices in support of enlargement and the spread of democratic values. That is why, EU has to do more to make sure the British voters will hear the EU point of view and interest. Alas, there is no such practise, apart from the European elections. "I tried to campaign in Britain during the European elections but I was not invited, so I don't see a reason to intervene in the now election campaign in Britain", said Jean-Claude Juncker with some superiority in response to a journalist question. But he is wrong.

A lot has changed since the elections for the European Parliament. As the Greek case shows, the election process may be a matter of national sovereignty but the consequences from it are not entirely national. Just like national parliaments have to approve a candidate to become a member of the EU, it is worth discussing across the EU the possibility of an exit of a member. EU should do exactly what Cameron's government did on the occasion of the referendum for Scotland's independence. And it has to do it now because 7 May is, symbolically speaking, the first round of the referendum on Britain's relations with the EU. A debate like the one that took place in Britain on Scotland's relations with the kingdom will have a strong healing effect on the continent as well where the eurosceptic forces are  becoming more and more and are growing stronger. The Commission and Donald Tusk should urgently develop a strategy on Britain.

becoming more and more and are growing stronger. The Commission and Donald Tusk should urgently develop a strategy on Britain.

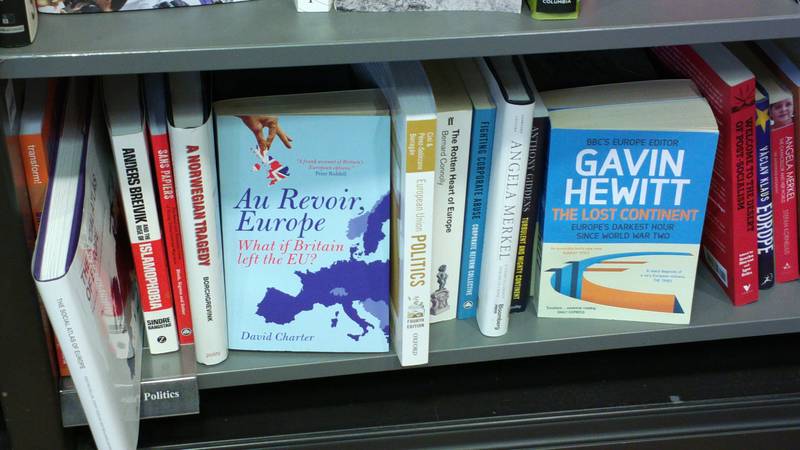

At the moment, the debate is left entirely on the national views. The books on Europe's flaws and a British exit are the first thing one can see in the British bookstores. The newspapers are overflowing of publications on the issue and various viewpoints are presented. Brussels, however, is silent and is watching neutrally the developments across the Channel and leaves the debate without the European point of view. This is a mistake and EU will pay dearly for its inaction. In addition, the current geopolitical moment is not at all good for such things. So, David Cameron's mission to change EU might be close to an impossible one but Brussels, too, has a mission which with every missed day is getting closer to impossible as well. This is the mission to keep the Union's integrity and its purpose. "Mr Tusk, your mission, should you choose to accept it, involves the recovery of a stolen item". This could be a paraphrase of one of the most famous quotes from the Mission Impossible movie. The item is the purpose of the EU.

| © Council of the EU

| © Council of the EU Jean-Claude Juncker, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU

Jean-Claude Juncker, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU | © Council of the EU

| © Council of the EU Jeremy Corbyn | © Labour

Jeremy Corbyn | © Labour | © euinside

| © euinside David Davis | © European Commission

David Davis | © European Commission Angela Merkel | © Council of the EU

Angela Merkel | © Council of the EU Michel Barnier, Nigel Farage | © European Parliament

Michel Barnier, Nigel Farage | © European Parliament | © euinside

| © euinside