Old Secret Police Still Active in Post-Communist Countries

Adelina Marini, January 15, 2015

The transition from totalitarianism/communism to democracy and market economy is not a straight line; the most unreformed countries are also the poorest; the old secret services are still a factor in the political life of many of the former communist countries; reforms are reversible. These are the most fundamental conclusions from the study of the transition of the countries from Central and South-Eastern Europe, including the post-Soviet countries, presented in the form of a book in mid-December in Brussels by Simeon Djankov, former deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria, in the office of one of the biggest European think-tanks Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS). Simeon Djankov is a co-author of the book and presented himself as a reformer together with Leszek Balcerowicz of Poland, Vaclav Klaus (ex-president of the Czech Republic), Mark Larr (ex-prime minister of Estonia), Ivan Miklos of Slovakia. With a contribution to the book are also reformers from Georgia and Hungary.

Another surprise from the presentation of the book was that the search of reformers in Russia and Ukraine failed. In Russia, because the few there refused to contribute because they did not feel comfortable writing about reforms that generally failed. And in Ukraine simply because there are no reformers. Similar is the case with Romania, although, through the years, there were reformers but it proved hard to select a concrete person or a group, explained Simeon Djankov who several times portrayed himself as a reformer in Bulgaria and as a person who is currently professor in the only school (private) in Moscow where economy and finance is taught in a western style.

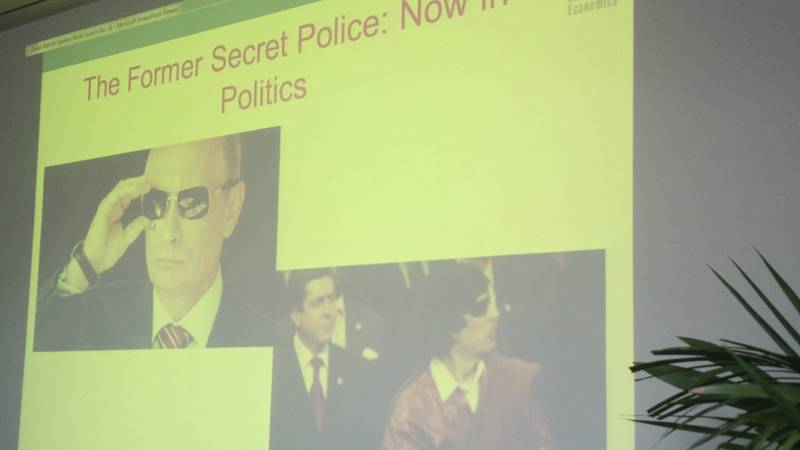

The role of the old secret police in many of the transition countries in the region was underestimated for a long time. The focus was mainly on the political parties - the communist parties and their role, should they be reformed or banned or should they be taken out of the political process. The discussion of the role of the secret services, however, in a majority of countries started much later in the process. There are several exceptions and that is the Czech Republic which adopted lustration laws early in the transition. In Hungary, this was not very successful but in the beginning there were discussions. In some countries, however, especially in Bulgaria, the former secret services are still very active both in the economic life (the banking sector) and the political life. According to Simeon Djankov, currently, there are two leaders of political parties in Bulgaria who are former officers of the secret services.

Later on during the presentation of the book he mentioned Georgi Parvanov, ex-president, who is currently a leader of one of the new parties that split from the Bulgarian Socialist Party (unconditional successor of the Communist party) - ABC - which is represented in parliament and even has a deputy prime minister in the current government - Ivaylo Kalfin. Russia is another good example because there the president is ex-KGB and where the most significant political players are from the same breed. At the moment, in the parliaments of nine former communist countries in the EU the leaders of major political parties are former members of the old secret police. Some of them, Mr Djankov said, have spent the entire transition as significant political players in their countries.

The loss of memory

He singled out another issue which, in his words, is still not researched seriously neither by the academia nor the policy-makers. It is the loss of memory. He quoted examples of opinion polls from many of the ex-communist nations, including in Bulgaria, which show that in 2014 many people either have no memory at all about the central planning, lack of democracy, the lacking goods or they consider the past better than the present. 25 years after the beginning of the transition on 10 November in Bulgaria 80% of the respondents in a poll published in November last year, aged between 16 and 30, say that they know nothing about communism. They have no idea what was then. The older generation, on the contrary, remember well and often those are painful memories, Simeon Djankov explained in front of a small audience consisting of representatives of the European institutions, the Russian embassy, Bulgarians living and working in Belgium.

He singled out another issue which, in his words, is still not researched seriously neither by the academia nor the policy-makers. It is the loss of memory. He quoted examples of opinion polls from many of the ex-communist nations, including in Bulgaria, which show that in 2014 many people either have no memory at all about the central planning, lack of democracy, the lacking goods or they consider the past better than the present. 25 years after the beginning of the transition on 10 November in Bulgaria 80% of the respondents in a poll published in November last year, aged between 16 and 30, say that they know nothing about communism. They have no idea what was then. The older generation, on the contrary, remember well and often those are painful memories, Simeon Djankov explained in front of a small audience consisting of representatives of the European institutions, the Russian embassy, Bulgarians living and working in Belgium.

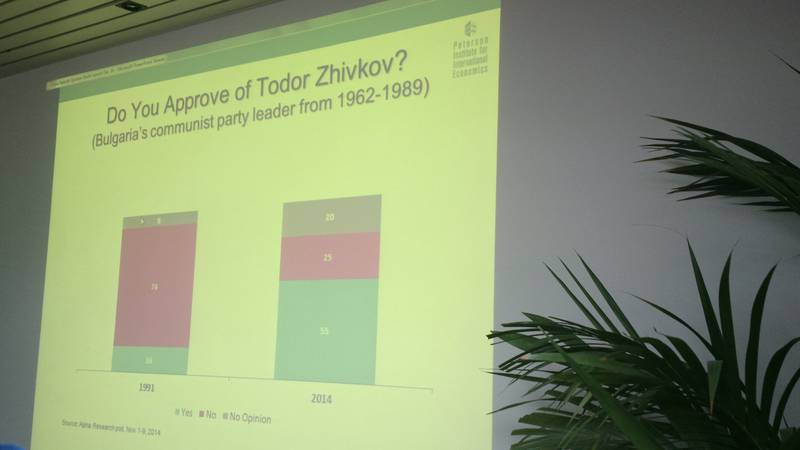

His favourite graph, as he said, is the one showing the results from the question "Do you approve of Todor Zhivkov?". In 1991, 76% of the respondents said "No", while in 2014 55% of the Bulgarians see him as a good guy. One of the reasons is that he was not active in politics as he died relatively early in the transition. It's worrying, the ex-finance minister said, that more than 20 years after the fall of communism many people believe that the last dictator was good because there were free schools, hospitals and other benefits. The picture is strikingly similar in most countries in the region. According to Simeon Djankov, the loss of historical memory in a combination with some lacking reforms not only in Bulgaria is the reason behind people's belief that the transition was, if not a complete failure, at least not very successful.

This is also one of the reasons for the rise of leaders like Putin in Russia and Orban in Hungary. To the West, this type of politicians seem charismatic populists, but in fact they reveal a very frightening trend. They are an example of what is to come in a significant number of states. Djankov did not exclude such leaders to appear in Bulgaria, Slovakia, Serbia and even in the Czech Republic because the population practically want them and create them. As a matter of fact, in Serbia this has already happened. The prime minister of the country, Aleksandar Vucic, is an adherent and an ally of Vladimir Putin. He is the Serbian example of one-man rule of a state which is in the very beginning of its path toward European accession. What the former expert in the World Bank, Simeon Djankov, missed to mention, however, is that Bulgaria too has (for a second time) such a leader. This is Prime Minister Boyko Borissov in whose first government Mr Djankov was a deputy prime minster and minister of finance. Mr Borissov's second cabinet is governing in a fragile coalition with reformers and extreme nationalists which is why his rule is not such a monocracy as before but the consequences from his previous government are still not dealt with.

Reforms are not an irreversible process

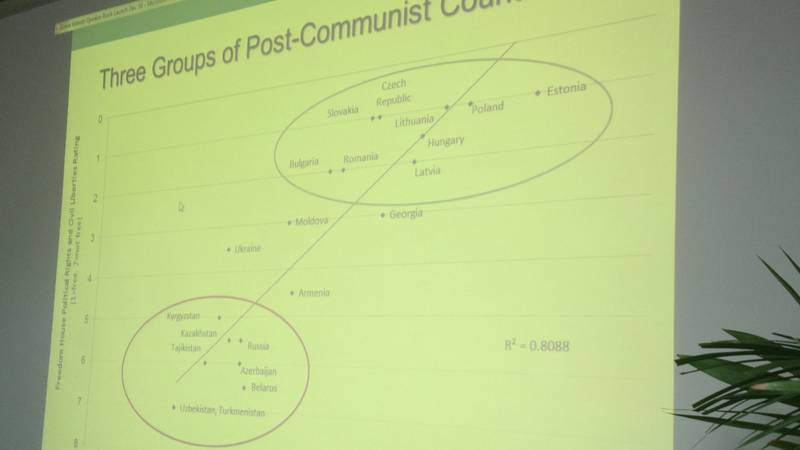

Simeon Djankov divided the countries from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union into three groups: reformers, non-reformers and those in the middle. In the first group are the post-communist countries that did essential reforms and currently there the corruption is less and they are generally democratic. In that group are the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, Latvia, Poland, Estonia. The second group consists of countries which in some sense have never done reforms. Those are Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Russia, Belarus, Turkmenistan. According to Mr Djankov, the most interesting group is that in the middle. In it are Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine and Armenia. These countries are a disputed zone of influence between Russia and EU. The difference between the first and  the other two groups is significant. In the first group, the income per capita has increased drastically. The biggest increase, according to the former finance minister, is in Estonia.

the other two groups is significant. In the first group, the income per capita has increased drastically. The biggest increase, according to the former finance minister, is in Estonia.

After ten years of deep reforms, the income of the Estonians increased from 44.9% of the EU average to more than 70%. In Bulgaria, the income per capita increased between 22% and 25%. There are six countries from the second and the third group which have gone poorer, which means that the income per capita has fallen in real terms. One of them is Ukraine. According to Simeon Djankov, this is the most striking example. In the beginning of the transition in 1992-1993, Ukraine was one of the wealthiest countries in the Soviet Union area when the income per capita was 2.5 times higher than in Russia. At the moment, 20 years later, they are half of the income of the Russians. Ukraine, together with Moldova, is among the poorest. In this group is Kosovo too, but it is a special case. The reason, according to Simeon Djankov, is in reforms.

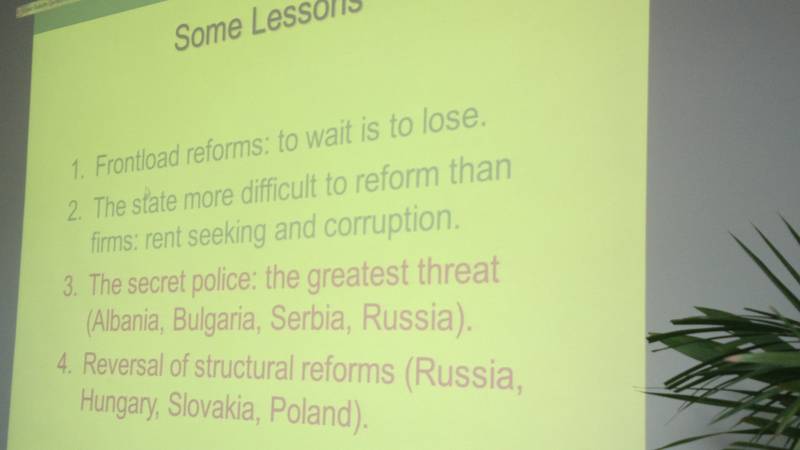

Reforms have to be done immediately, in the first 3-4 months of government. To wait is to lose. Even if you are not sure what to do, do it, said Simeon Djankov quoting his own experience in Bulgaria. In the beginning, he explained, it was believed that the transition is a transition from state property to private property. That is why, a large part of the efforts was aimed at privatisation, trade liberalisation, opening of the market. To a great extent all the countries from Eastern Europe which are now in the EU or on their way, did this part successfully. The problem, however, are the political reforms - the state institutions and the political parties. That reform takes much more time, it is very difficult and a delay of the process leads to rent-seeking and corruption, which still plagues many of the countries in the region.

This is to some extent a reflection of the economic conflict shock therapy vs. gradual reforms. Reformers like Balcerowicz and Chubais in Russia are supporters of the shock therapy because if reforms are prolonged opposition starts to build up. Among the bright supporters of the other model is Joseph Stiglitz, and American economist, a Nobel laureate in economy. With a hindsight and during writing the book, the authors found something else. According to them, the confrontation was not between the shock therapy and gradual reforms but about the role of the secret services as mentioned in the beginning of this article.

Another important conclusion the authors of the book reached is that reforms are completely reversible, again, in countries where some processes have not been completed. Although Russia and Hungary are the most frequently quoted examples, in fact many of the viewed countries in the past years show a retreat from some significant reforms. For example in Slovakia and Poland in terms of pension reform. Last year Bulgaria joined them, said Simeon Djankov, with its attempt to nationalise the second pillar of the pension system which is still debated and the decision is not final. The reversibility of the reforms consists of fast increase of the state property in the area of finance and resources (oil, gas). The most vivid example is Russia as the reversibility there started in 2003, which means from the beginning of Vladimir Putin's rule.

In addition to nationalisation of the pension systems another indicator of reversibility is the partial nationalisation of the pension systems. The subsidising of loss-generating state-owned enterprises and re-nationalisation is another indicator of reversibility. Such a process has begun in 2013 in Bulgaria. In Hungary, a new monopoly was created over the sale of "strategic products' like tobacco. The indicators vary from a country to country but, generally, the trend affects many countries, including Serbia.

Is the euro area a solution?

The accession of Latvia last year to the euro area and the last Baltic state - Lithuania - joining in on 1 January 2015 - was accompanied by the thesis that this is the last stage of their transition and that it actually marks the end of the European integration understood as market economy and democracy. I asked the former deputy prime minister of Bulgaria whether he agrees with such a thesis. He did not. Not only that this is not the last step of the economic transition but surely it is not the last of the overall transition. The reason is that there are sectors in the Baltic economies that still remain unreformed. Most of all, the energy sector which is a problem for many of the countries in the former communist camp, including Bulgaria, because the sector depends to a large extent on Russia or, generally speaking, on supplies from state-owned companies. This is a significant sector of the economy where there is a lot of money and therefore lots of conditions for corruption. As a matter of fact, the reform of the energy sector  is one of the country-specific recommendations for Bulgaria, the Baltic states, Poland and other countries from the former Eastern Europe.

is one of the country-specific recommendations for Bulgaria, the Baltic states, Poland and other countries from the former Eastern Europe.

Membership in the euro area, however, gives some guarantees. Simeon Djankov gave the example of the Corporate Commercial Bank (KTB) of Bulgaria without explicitly naming the bank. According to him, being part of the euro area is useful because it takes away the possibilities for state corruption and rent-seeking in the banking sector. "I would have thought, maybe, six months ago that this is not as important in a well organised country like Latvia, you saw what happened in Bulgaria - an institution that was successful basically had gone". The main reason for this are the bad supervisory practises, Simeon Djankov explained. If Bulgaria were part of the eurozone, this would have never happened, he is convinced. At this stage, however, the Bulgarian government plans to join only the banking union and more specifically only a part of the union, which has proved impossible.

I also asked Mr Djankov whether the Commission had ignored the economic reforms in the process of accession which it is currently trying to compensate by introducing a light version of the EU economic governance (the European semester) for the countries from the enlargement process. Simeon Djankov criticised that too. According to him, the Commission was "unrealistically optimistic" regarding the development of the situation in the first years and the economic reforms it required were just for the sake for appearances. The European semester is for form's sake at the moment too, he believes, because the Commission does not have the expertise and the countries are generally doing whatever they had planned. It is not hard to find proof nowadays. The examples of France and Italy suffice. But still, he was an optimist that with time the Commission will gain expertise and the process will be useful. Regarding enlargement, the mistake was that it was expected once a country joined it would immediately transform into a new wonderful case of European democracy, European institutions and European economies.

Alas, this requires huge efforts. The mistake is that the Commission put too general conditions. For example, the fight against corruption. In Mr Djankov's words, it had to be more specific - handle corruption in the energy sector, in the banking sector, in the judiciary and this should have been pursued vigorously. The thinking then was too simplistic. There is still not sufficiently good understanding of how to transform institutions. Some countries were lucky, like Slovakia for instance, which after separating from Czechoslovakia, had to build the state from scratch. But this did not begin immediately. Not until the appearance of the first reformist government led by Ivan Miklos who succeeded Vladimir Meciar. That is why, this country is an example of the most successful transition, Simeon Djankov believes. May be, it is worth mentioning here the example of Croatia which, too, had to build an independent state from scratch relatively recently. According to Djankov, one of the reasons for Slovakia's success is the EU. The European integration served as an anchor. If this anchor is not there the political class can easily get corrupt and unleash a process of reversing of reforms.

Though concise, Simeon Djankov's presentation presents a serious quantity of food for thought and development of policies and strategies. The question that has remained unanswered is whether the reversibility of reforms is reversible? In other words, is it possible the countries that go backward to start moving forward? According to Simeon Djankov, there are countries which showed that after a semi-autocratic leader left they get back to normal in the European sense. The question is, however, is this possible in countries where the former secret services are still influential in the national politics.

Though concise, Simeon Djankov's presentation presents a serious quantity of food for thought and development of policies and strategies. The question that has remained unanswered is whether the reversibility of reforms is reversible? In other words, is it possible the countries that go backward to start moving forward? According to Simeon Djankov, there are countries which showed that after a semi-autocratic leader left they get back to normal in the European sense. The question is, however, is this possible in countries where the former secret services are still influential in the national politics.

Mark Rutte, Alexander Stubb | © WEF

Mark Rutte, Alexander Stubb | © WEF Mogherini, Renzi, Tusk | © European Council

Mogherini, Renzi, Tusk | © European Council Boyko Borisov | © Council of the EU

Boyko Borisov | © Council of the EU