No Drama so far in the Selection of a Successor to Laura Codruta Kövesi as Head of the European Public Prosecutor's Office

Adelina Marini, LL.M., January 13, 2026

Four years after becoming operational, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) has proven itself an effective supranational institution under the leadership of Laura Codruta Kövesi, the Office's first Chief Prosecutor. Her non-renewable 7-year term ends on the 31st of October 2026. The inter-institutional negotiations are underway to appoint a successor. Since this is only the second time a European Chief Prosecutor is to be appointed, it is worth revisiting the process of 2019 and to compare it with the current one, in order to see the differences. This will help understand better which factors play major role in the appointment process.

Four years after becoming operational, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) has proven itself an effective supranational institution under the leadership of Laura Codruta Kövesi, the Office's first Chief Prosecutor. Her non-renewable 7-year term ends on the 31st of October 2026. The inter-institutional negotiations are underway to appoint a successor. Since this is only the second time a European Chief Prosecutor is to be appointed, it is worth revisiting the process of 2019 and to compare it with the current one, in order to see the differences. This will help understand better which factors play major role in the appointment process.

Kövesi's appointment in 2019 was preceded by intense negotiations between the European Parliament and the Council, which risked politicising an institution whose main purpose is to be independent from the EU institutions and the Member States. Thanks to Laura Codruta Kövesi’s impeccable record as a brave fighter against high-level corruption, the EPPO, under her stewardship, gained a reputation of a supranational institution capable of dealing with tough challenges and recalcitrant national authorities.

What does the current process of selecting a successor tell us about the challenges the EPPO is facing? This contribution has two main objectives. One is to shed more light onto the process of appointment of the European Chief Prosecutor and, two, to present the candidates’ views about the main challenges in front of the EPPO and how they plan to address them.

Since the structure of the EPPO is divided into a central layered level and a decentralised level, the appointment procedure of the European Chief Prosecutor is only one of the tests for the Office’s independence - a test that depends to a large extent also on the tasks and responsibilities of the position. The European Chief Prosecutor is responsible for organising the work in the EPPO, directing its activities, taking decisions, and representing the institution externally (Article 11 of Regulation (EU) 2017/1939 - the EPPO Regulation).

In addition, the ECP chairs the meetings of the College - a body responsible for organising the internal work of the institution (Article 9) - and the Permanent Chambers (Article 10(1)). Importantly, the ECP plays an important role in the appointment of European Delegated Prosecutors (Article 17(1) and (4)).

The choice of an ECP is the most transparent process as compared to the selection of European Prosecutors (EPs) and European Delegated Prosecutors (EDPs). This is due, first, to the fact that an open call for appications is published in the Official Journal of the EU. Second, the appointment depends on the agreement of two EU institutions - the European Parliament and the Council (mentioned in this order in Article 14 (1) of the EPPO Regulation). Third, the European Parliament holds hearings of the candidates shortlisted by the selection panel, which has 12 members. They are former members of supranational judicial institutions such as the Court of Justice of the EU, the Court of Auditors of the EU, Eurojust.1 . Members of the panel can also be national supreme court judges, high-level prosecutors or lawyers of recognised competence (Article 14(3)).

These hearings are public as is the information about each candidate and how they responded to a questionnaire provided by the Parliament. The process within the Council, however, is covered by secrecy - there are no public hearings, statements or discussions of the qualities of the shortlisted candidates. The Council adopts a decision on a preferred candidate before the start of the negotiations with the Parliament.

The requirements for the position of an ECP are that an applicant must be an active member of a national public prosecution service or judiciary, or (as is the case this time around) a European Prosecutor (Article 14(2)(a)). That person’s independence must be unimpeachable (Article 14(2)(b)). Her/his qualifications must be comparable to those of a candidate for the highest prosecutorial or judicial offices in the Participating States, and, in addition, the candidate must have experience with financial crime and international judicial cooperation in criminal matters (Article 14(2)(c)). Last but not least, a successful candidate must have sufficient managerial experience (Article 14(2)(d)).

After reviewing all applications, the selection panel draws a list of 3-5 eligible candidates and interviews them and sends it to the European Parliament and the Council. The ranking of the candidates by the panel is not binding on either of the two institutions,2 thus leaving the political wing significant room for manoeuvre. However, if a candidate is found by the panel to not meet the criteria, this decision is binding on the Parliament and the Council.

The appointment procedure in 2019

When the first ever European Chief Prosecutor was to be appointed, the process was accompanied by a big political drama. First, it coincided with the European elections and the subsequent haggling among the Member States over the top-jobs – a moment when various factors come into play, most importantly geographical, political and gender balance. The selection panel made a shortlist of three candidates: Laura Kövesi (Romania), Jean Francois Bohnert (France), and Andres Ritter (Germany). The panel ranked Ms Kövesi first.

The shortlisted candidates were heard at a joint session of the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) and the Committee on Budgetary Control (CONT) on 26 February 2019. In the voting that followed in CONT, Ms Kövesi received the support of 12 MEPs, followed closely by Mr Bohnert with 11 votes. Only one MEP voted for Mr Ritter in that committee. In LIBE, 26 MEPs voted for Kövesi, 22 for Bohnert, and Ritter, again, received only one vote.

Apart from being very well qualified for the job, Ms Kövesi earned the European Parliament’s support because of her impressive professional record in her home country, Romania. She began her career as a prosecutor general in 2006 – right before Romania was set to join the European Union together with Bulgaria on January 1st 2007.

However, one major obstacle was lying ahead of Romania’s accession – corruption was widespread, especially at the high-levels, and the country was failing to guarantee, in law and in practice, the independence of the judiciary. Kövesi’s appointment as prosecutor general, proposed by then-Minister of Justice Monica Macovei and backed by then-President Trajan Basescu, was meant to ensure that Romania could and would demonstrate political will and capacity to fight high-level corruption.

The appointment came a bit late and Romania joined the EU with a post-accession conditionality - the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM) - the main objective of which was to monitor and support Romania in its effort to establish rule of law and to demonstrate a solid track-record in fighting high-level corruption. In 2012, five years into the CVM, the Commission got impatient with Romania and threatened sanctions if the government did not follow its recommendations.

Amid a severe political, constitutional and social crisis, Laura Codruta Kövesi was appointed, in 2013, head of the National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA), where she launched many investigations of ministers, deputy ministers, mayors and other high-level officials. Her name quickly rose to fame not only in Romania but also in neighbouring countries struggling with the same problem.

After a change of government in 2016, she lost political support and became the object of a fierce campaign to remove her. She was ultimately dismissed in 2018. It is in this context that she emerged as one of the main contesters for the newly opened position of European Chief Prosecutor. The Romanian government campaigned hard in the Council against her, which was why, the Council’s candidate initially was Jean Francois Bohnert. This set the course for a major clash with the European Parliament. After three rounds of tough negotiations, the two institutions were deadlocked.

The Parliament argued that the Council should not yield to the pressure of the Romanian government and underlined the importance of courage and independence for the ‘efficient functioning of the EPPO’. The Parliament also criticised the Council for not being transparent in its selection process.

In an unexpected turn of events, France gave up its support for Jean Francois Bohnert and stood behind Kövesi instead. This move led to a situation where the two leading candidates lost the support of their home countries in the Council. Ultimately, the fact that Ms Kövesi is a woman, coming from an under-represented country in the context of the EU top-jobs negotiations, and having a stunning record of professional independence led to her appointment. Jean Francois Bohnert is currently one of the 12 members of the selection panel.

The appointment procedure in 2025/2026

The situation seven years later is very different. There are no European elections to interfere with the process of appointment; geographical and gender balance still matter but the stakes are not as high. Rule-of-law backsliding and the normalisation of anti-democratic and anti-rule-of-law political forces have gained traction at the supranational level – both in the European Parliament and the Council. Some governments in the Council suffered major losses due to the EPPO’s effectiveness and started attacking the institution.

An illustrative example is Croatia where the EPPO launched multiple investigations into high-level corruption causing many ministers, deputy ministers, regional leaders and other high-level officials to lose their positions to criminal investigations. After initially supporting the EPPO’s work, Prime Minister Andrej Plenković became openly hostile to the institution. The appointment of Ivan Turudić as State Attorney General led to the first conflict of competence in a major corruption investigation.

Croatia is not the only Participating State that made the job of the EPPO harder if not impossible. The authorities in Greece and Slovakia also tried to prevent the EPPO from investigating major high-level corruption cases. In Bulgaria too, the EPPO faced significant challenges. This is the context in which the selection of the next European Chief Prosecutor is taking place.

The third candidate who became first

Despite the political changes in the European Parliament and the Council, so far the process of selection of the next European Chief Prosecutor seems rather technocratic. In April 2025, the Official Journal published a call for candidates for the position of a European Chief Prosecutor.3 Seventeen candidates applied. The selection panel shortlisted four of them: Andres Ritter (Germany), Ingrid Maschl-Clausen (Austria), Emilio Jesus Sanchez Ulled (Spain), and Stefano Castellani (Italy).

After the candidates submitted written answers to a questionnaire from the European Parliament, on the 3rd of December the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs and the Committee on Budgetary Control of the European Parliament conducted a hearing, in a joint session, of the four shortlisted candidates to succeed the highly popular Romanian Laura Codruta Kövesi as head of the European Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Andres Ritter, who was the third candidate in 2019, has been one of the two Deputy European Chief Prosecutors for five years. Previously, he was a Deputy Prosecutor General of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and subsequently Chief Prosecutor of the Public Prosecution Office for Economic Crime and Cybercrime in Rostock.

Stefano Castellani is a European Delegated Prosecutor from Turin. The EPPO has eight regional offices in Italy: in Rome, Milan, Bologna, Naples, Palermo, Turin, Venice, and Bari. Some MEPs raised concerns that he lacks managerial experience.

Ingrid Maschl-Clausen was the first Austrian European Prosecutor. She was also a Eurojust national member and a justice counsellor in Austria’s Permanent Representation. The focus of her previous work as a prosecutor in Austria was on corruption.

Emilio Jesus Sanchez Ulled is considered to be the external candidate as he has never worked in the EPPO. He is an anti-corruption prosecutor who served as a justice counsellor in Spain’s permanent representation to the EU. His specialisation is also high-level corruption cases.

The four candidates were heard by the two responsible committees in a joint session. The order of the hearings is determined by a lottery. As a general rule, the MEPs asked very similar questions to each candidate but there were also specific questions meant to clarify issues related to qualifications and/or reputation. The questions can be grouped into the following categories: candidates’ qualifications; experience; their views about the main challenges affecting the EPPO’s effectiveness; should the EPPO’s competences be expanded; what amendments should be made to the EPPO Regulation; how to improve the Office's effectiveness, including the recovery of confiscated assets. These follow the written questions submitted to the candidates

The four candidates shared some views regarding the challenges but differed as to what must be done to address them. According to the lottery, Castellani was heard first, followed by Ingrid Maschl-Clausen, Emilio Jesus Sanchez Ulled, and Andres Ritter. Castellani did not shy away from sharing his views about expanding the EPPO’s competences to cover traffic of waste and circumvention of EU sanctions, whereas Sanchez Ulled considered this to be a matter for the legislator. A similar position took Andres Ritter.

Among the proposed amendments of the EPPO Regulation, which is currently under review in the European Commission, was Article 8, which describes the structure of the EPPO as an ‘indivisible’ EU body operating as a ‘single office’ with a decentralised structure. As a way to strengthen the single office, Castellani proposes several measures, inter alia regular inter-regional meetings between the EDPs to ensure sharing of knowledge and expertise about the different systems. This obviously concerns the cross-border dimension of investigations suggesting that, if appointed, he would prioritise cross-border investigations, as this is his area of expertise. Another idea of his was to improve communication among EDPs and data exchange through technology.

Ritter proposed amending Article 4 of the Regulation according to which the EPPO is competent only until the case has been finally disposed of, which he sees as problematic. Article 38 also needs to be amended in order to clarify how the EU’s financial rights are to be protected when assets are confiscated. The issue of funds recovery was a major one for the Parliament because, after a final court decision, it is the national authorities that deal with recovery. Very often the confiscated assets are not returned to the EU budget.

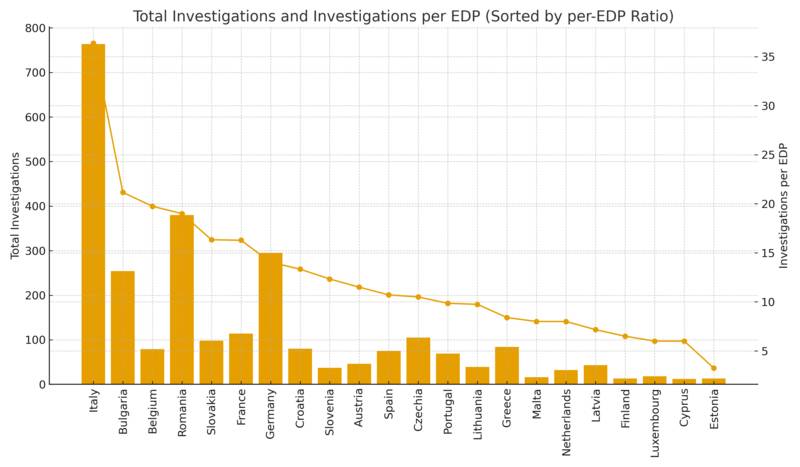

Some of the candidates insisted on the need for more EDPs, special training, and specialised investigators. The burden for EDPs is particularly acute in some Participating States struggling with a very high number of active investigations, such as Italy.

Some of the candidates insisted on the need for more EDPs, special training, and specialised investigators. The burden for EDPs is particularly acute in some Participating States struggling with a very high number of active investigations, such as Italy.

Despite her very good CV and clear, experience-driven ideas, Ingrid Maschl-Clausen’s application was killed after two serious issues were raised by several MEPs and which dominated her hearing. The first was related to Maschl-Clausen’s failed attempt to get appointed as an EDP. Details on the subject were scarce, so the information provided here is based solely on the discussions during the hearing. It seems there was an occasion when she met a person with whom she might have been in a conflict of interest.

It was claimed that she failed to inform the European Chief Prosecutor as required by the internal rules of the EPPO. This was the reason why her application for the position of an EDP was rejected. However, Maschl-Clausen claims she did nothing wrong and reduced the issue to a clash of views between her and the ECP. She said she asked the ethics committee for an opinion and was cleared of any wrongdoing. This did not seem to convince the MEPs, who continued to press her on this issue.

The second problem that emerged in MEPs’ questions were claims that the Austrian government lobbied heavily for her application for the position of European Chief Prosecutor. Maschl-Clausen referred in her defence to a statement by the Austrian minister of justice, Dr. Anna Sporrer, which she interpreted as meaning only that the minister trusted Maschl-Clausen’s independence. This exchange highlights the importance of transparency of the appointment process in order to expose attempts by governments to influence the work of the EPPO.

On several occasions she repeated she had different views from those of the current European Chief Prosecutor and tried to frame it as an advantage, as a demonstration of her ability to withstand pressure. This did not sit well with many of the MEPs who keep Laura Codruta Kövesi in very high regard and kept reminding all the candidates that she was leaving big shoes to fill.

The candidates were asked whether they would prioritise a certain offence. This, however, seemed more like a trap, in which Sanchez Ulled fell by saying that corruption was his professional career and he would focus on that type of offence. This was in contrast to Maschl-Clausen’s response that the EPPO is based on the legality principle (Recital 66). All candidates were asked whether they consulted with their national governments before applying for the position and how they would resist political pressure.

After the hearings, Andres Ritter emerged as the Parliament’s favourite. In CONT, he received 22 votes, Sanchez Ulled - 2, and Castellani - 1 vote. It seems nobody voted for Ingrid Maschl-Clausen as the committee chair did not mention her name when revealing the results from the vote with paper ballots. At a subsequent vote in LIBE, Ritter received the support of 46 MEPs, Castellani – 11, Sanchez-Ulled – 7, and Maschl-Clausen – 4.

The Council has also been busy and it seems there is a decision on who their candidate would be but it is not yet made public. Negotiations are under way between the Parliament and the Council. However, it does not seem there will be any drama this time and it is very likely that Andres Ritter will be the next European Chief Prosecutor.

When asked whether he would have Laura Kövesi’s courage, he said it was the EDPs that were on the front line, facing direct pressure and even personal threats. He admitted he was no match for Kövesi but was determined to guide the evolution of the EPPO. He was the only one asked how he would deal with rule of law backsliding Participating States. If there was a serious breach, the EPPO would flag it, he said. This was the case with Slovakia and Croatia, which were flagged by the EPPO under the conditionality regulation – Slovakia for adopting legal amendments that would make the EPPO’s work very hard and for amendments aimed at preventing whistleblowing; Croatia for conflict of competence, which the State Attorney General resolved without consulting the EPPO in a very short time.

Ultimately, Ritter said, it is up to the Commission to act on such cases. Laura Kövesi has been very outspoken regarding situations like these. Coming from Romania, she has a good nose for recognising foul play by the national authorities. The question is whether Ritter would be as sensitive to this problem or would he be technocratic in his approach. His vision is continuity but also evolution now that the EPPO has a very strong foundation. This assessment, however, has been questioned regularly by governments allergic to independent anti-corruption investigations through legislative amendments and/or appointments.

1 ‘Council Decision (EU) 2023/133 Appointing the Members of the Selection Panel Provided for in Article 14(3) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1939’.

2 ‘Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/1696 on the Operating Rules of the Selection Panel (Article 14(3) of Regulation 2017/1939’ art VII(1).

3 ‘Open Call for Candidates for the Position of European Chief Prosecutor’.