Croatia: The EPPO at the Centre of the Fight against Political Capture of the Judiciary

Adelina Marini, LL.M, November 28, 2024

Since it became operational in 2021, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) has been very effective in Croatia with many of the investigations against corruption and abuse of office by public officials, including high-level, concluding with final judgments in national courts. As an illustration, in 2022, 23 new investigations for an estimated amount of EUR 314 million were opened, the EPPO filed 8 indictments, and the year ended with 6 final court decisions. Corruption was the most frequent type of fraud in 2022. Croatia had the second largest number of newly registered cases reported to the EPPO (17).

Since it became operational in 2021, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) has been very effective in Croatia with many of the investigations against corruption and abuse of office by public officials, including high-level, concluding with final judgments in national courts. As an illustration, in 2022, 23 new investigations for an estimated amount of EUR 314 million were opened, the EPPO filed 8 indictments, and the year ended with 6 final court decisions. Corruption was the most frequent type of fraud in 2022. Croatia had the second largest number of newly registered cases reported to the EPPO (17).

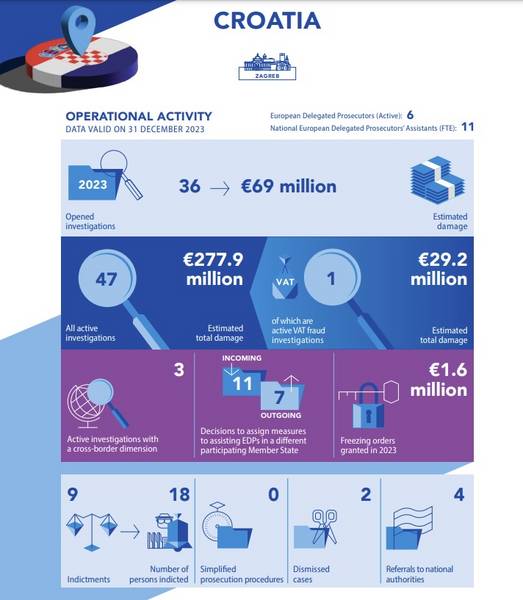

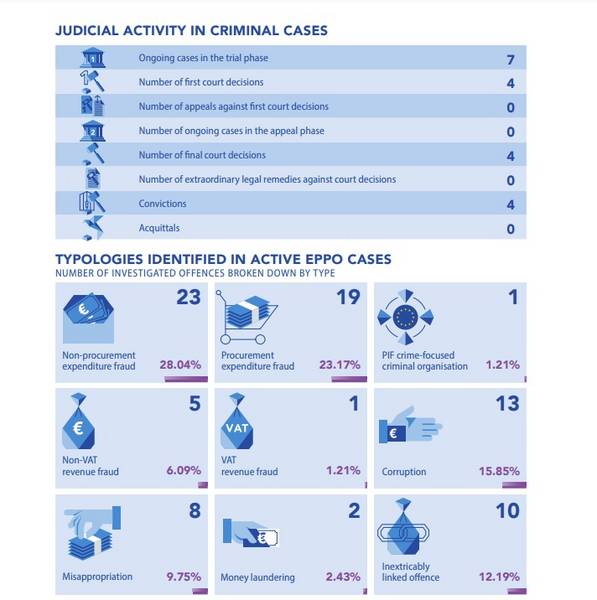

In 2023, 36 new investigations were opened for a total estimated amount of EUR 69 million, the EPPO filed 9 indictments against 18 individuals, 7 cases were in the trial phase, and there were 4 final court decisions. Corruption was the third most frequent type of fraud investigated by the EPPO last year. Another interesting data from the EPPO’s 2023 annual report is that Croatia had the highest number of reports sent to EPPO by private parties (433). It may, therefore, be said without exaggeration that Croatia has so far been one of the most successful EPPO participating states generally and the most effective one when it comes to investigating high-level corruption. Effectiveness (and therefore success) are measured by the number of final court decisions.

This significantly raised hopes in society that a supranational EU institution may be succeeding where national institutions have persistently failed, namely, holding public officials accountable. At least, when EU crimes are involved, which very often is densely intertwined with national ones (the so-called inextricably linked offences). But is this success story coming to an end? Is the EPPO en route to become a victim of its own success in Croatia? This question arose earlier this year when the first visible conflict emerged between the EPPO and the government and which loomed even larger with the investigation announced on the 15th of November, involving the former Minister of Healthcare Vili Beroš.

This year may very well be marked by the first visible signs of attempts to reduce the EPPO’s effectiveness. With the objective of shedding light on a dynamic development, which may signify rule of law backsliding, this article will start with background of how the conflict between the government and the EPPO started, followed by a brief presentation of the latest investigation and concluding with some recommendations.

EPPO has become the nightmare of Andrej Plenković’s government

The numbers above do not say much about the scale and significance of the work the EPPO has been doing in Croatia in the past 3 years. Despite the fact that several minsters were investigated and some of them ended up in prison, there seemed to be no visible problem with the work the EPPO was doing. On the contrary, the EPPO enjoyed full support from the government, including the prime minister, and the local judiciary with only minor statements of frustration expressed to the effect that the EPPO had made the USKOK (the national office for the prevention of corruption) obsolete. Croatian media at the time even suggested that the reason why the EPPO was so successful was that Prime Minister Andrej Plenković (HDZ/EPP) had no influence over it, unlike the State Attorney General's Office.1

The tipping point came last year, when 29 Croatian citizens were arrested in the largest investigation of the European Public Prosecutor’s Office so far in Croatia. The subject of the investigation is suspected fraud with subsidies and public procurement in the Faculty of Geodesy of the University of Zagreb. Among the arrested was the Dean of the faculty and a professor. The reason why that investigation was initiated by the EPPO was that the faculty organised public procurement procedures for projects funded up to 85% from the EU budget.

The investigation caused significant public backlash because some of the projects involved activities related to dealing with the aftermath of the disastrous earthquakes that hit Croatia in 2020 and 2021, when the small town of Petrinje was almost completely destroyed and many old buildings in the city of Zagreb suffered significant damage. One of the projects was to conduct a 3D survey of the cultural heritage buildings that were affected during the 2020 earthquake.

Allegedly, the suspects, among whom was also a former assistant of the Minister of Culture and Media, arranged the procurement procedures in such a way that specific companies were approved in exchange for a share of the profit. According to the EPPO estimates, the damage to the EU’s financial interests amounts to EUR 1 715 017 of a total financial damage of over EUR 2 million. Even though, initially, the government and, more specifically, Minister Nina Obuljen Koržinek seemed to cooperate with the EPPO and announced publicly that the very fact of the investigation meant the Ministry was cooperating and helping, the moods changed dramatically.

After the opposition turned corruption under Andrej Plenković as their main campaign message for the parliamentary and the subsequent European elections last spring, the knives were out and this investigation found itself at the centre of the first major conflict between the government and the EPPO. When responding to questions about the affair, PM Andrej Plenković (HDZ/EPP) demonstrated an even more toxic disdain for journalists, especially female ones. His object of frustration was how well informed journalists from independent media were when questioning his claims that the EPPO had no competence to investigate these cases, alluding that they may have been instructed by someone as if this is a crime.

Another major development in the wake of the investigation, was the decision of the ruling majority in the Sabor (the Croatian Parliament) to appoint Ivan Turudić as Attorney General to replace Zlata Hrvoj Šipek. This was a major development because the Attorney General plays an essential role in cases of conflicts of competence with the EPPO (more on this below). Turudić is considered by many a controversial figure because of his too close relations with high-level suspects. Opposition members of parliament and independent media feared his appointment might be aimed at preventing the EPPO from further prosecuting members of the government and others close to the ruling party HDZ.

One reason for these concerns are statements to that effect by Turudić himself. In an interview (HR) he openly stated that Croatia did not need the EPPO and that many Member States were doing very well without it, which is still an inaccurate statement, since, by the time of the statement, only five Member States were not yet participating in the EPPO: Denmark, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, and Sweden. As of today, Poland and Sweden have joined the enhanced cooperation establishing the EPPO, and Ireland is also considering it, leaving only Denmark and Hungary outside.

Among the expressed concerns were that Turudić would use his powers to sabotage EPPO investigations by claiming the EPPO is not competent to investigate certain cases and that he would warn the government or interested parties about upcoming investigations.

The first fear is based on the fact that, according to the Croatian act (HR) implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1939 establishing the EPPO, the power to decide in cases of conflicts of competence (Article 25 of the Regulation) is given by the Croatian legislator to the Attorney General without any possibility to challenge his decisions (Article 8 of the act implementing the EPPO Regulation). Article 25 of the EPPO Regulation is not very helpful in such cases as it creates more problems than it solves. Article 25(1) of the Regulation is clear in giving the EPPO the power to exercise its competence to initiate an investigation under Article 26 or to use the right of evocation under Article 27. In such a situation, the national authorities shall not exercise their own competence for the same offences (2nd sentence).

However, Article 25(6) also clearly states that in cases of conflict of competence, the national authorities shall resolve the conflict. It is left to the Member States to decide which national authority will decide in such situations (last sentence). It is important to note that paragraph 6 refers only to situations of disagreement as to whether the offence falls within the scope of Article 22(2) or (3) or Article 25(2) or (3). This means that, when an offence falls clearly within the material scope of the Regulation, the EPPO, once it has initiated an investigation, remains in charge, according to Article 25(1). The national competent authority can decide only when there are disagreements on whether an offence falls within the material scope. Article 8 of the Croatian implementing law refers specifically to Article 25(6) of the Regulation.

As Herrnfeld notes in his excellent analysis of Article 25,2 even though the Member States are given the power to establish which national authority should decide in situations of conflict of competences, Article 42(2)(c) of the Regulation clearly expects that authority to be able to refer questions to the Court of Justice pursuant to Article 267 TFEU. An Attorney General does not fit into the category of a ‘court or a tribunal established by law’ as Article 267 TFEU requires and as clarified by the CJEU case law. And yet, there were voices who recommended this authority to be precisely the Attorney General in Croatia (Bonačić).3

The EPPO Regulation is based on mutual trust and, although not explicitly, on the assimilation principle,4 which presumes that the national authorities are very strict in protecting their own financial interests and therefore are expected to be equally strict in protecting the EU’s interest. This presumption, however, does not stand the test in situations of political or other capture of the judiciary. It cannot answer the question what if a Member State is not strict in protecting its own financial interest? What if a government not only does not protect it but benefits from corruption?

The concerns mentioned above received partial confirmation by the successful rejection by the ruling majority of attempts by the opposition to push for amendments to the act implementing the EPPO Regulation. In January, Možemo! (European Greens), filed a proposal to amend the law by introducing a new paragraph allowing decisions by the Attorney General to be reviewed by the Supreme Court within 7 days. This, the Možemo! parliamentary group explained, would allow judicial review and, ultimately, only courts can send preliminary ruling requests to the Court of Justice pursuant to Article 267 TFEU. The Attorney General cannot.

With similar arguments, the second largest political group in the Sabor, SDP (PES), tabled another proposal (HR) for amendments in May which, however, removed the Attorney General’s powers to decide on conflicts of competence. Instead, the SDP proposed a judge from the High Criminal Court to make that decision, which, again, can be subject to judicial review by the Supreme Court within 8 days from the delivery of such a decision.

The Croatian government sent, in July, an opinion on the matter asking the Sabor to reject the SDP proposal with the main argument being a study by a group of academics, ordered by the European Commission. This study found that Croatia is among many of the Participating Member States that have not implemented the Regulation properly.

The Opinion claims the Commission is yet to analyse the study and emphasises that it is not binding on the Commission. With this in mind, the Croatian government states that unless the Commission confirms the problems with the implementation officially, the law should not be amended thus keeping the powers of the Attorney General to decide in cases of conflict of competence with the EPPO and therefore not allowing requests for preliminary rulings to be sent to the CJEU. How does this all connect to create the first major conflict of competence between the national prosecution authorities and the EPPO in Croatia? This is the subject of the next section.

The medical robotics procurement for hospitals

On November 15th, the EPPO announced the initiation of an investigation against eight people suspected of accepting and offering bribes, abuse of office and money laundering. Among them, the press release said, was the former Minister of Health. The individuals allegedly participated in a criminal organisation with the objective to ensure that specific companies would be selected for the public procurement of high-tech equipment for hospitals at much higher prices. The former Minister is suspected of receiving bribes, together with the directors of two hospitals, to ensure the companies in question would receive contracts financed both by the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) and the national budget.

Only one project was supposed to be financed by the RRF for the purchase of robotic equipment for surgeries for the Clinical Hospital Center in Split, but its director refused to take part in the scheme. According to media reports, he was subjected to intense pressure and ultimately resigned. It is unclear from the EPPO press release whether the other projects, which were successful, were to be financed by the RRF or only by national funds.

On the next day, November 16th, the Office for the Prevention of Corruption and Organised Crime (USKOK) announced that, ‘on the basis of inspections it did on its own’, it decided, on 15th of November, to start an investigation (HR) against three individuals suspected of abuse of office, influence trade, offering and accepting bribes in the framework of an organised criminal group. The USKOK press release mentions that the former Health Minister is involved and that funds from the Croatian budget are at stake but omits to mention the owners of the companies who are part of the EPPO’s investigation. USKOK asked the district court in Zagreb to order the arrest of two of the suspects. For the third one, it claimed, the conditions were not fulfilled.

Thus, in fact, two parallel investigations were at play – one involving eight suspects and the other three – and presumably a conflict of competences was created, which raises a ne bis in idem situation. On November 19th, the Attorney General decided (HR), on the basis of Article 8 of the act implementing the EPPO Regulation, which transposes Article 25(6) of the Regulation, to take over the investigation from the EPPO with the following arguments. First, he explained that USKOK filed a proposal on the 15th of November asking him to resolve the conflict of competences with the EPPO in its benefit.

– and presumably a conflict of competences was created, which raises a ne bis in idem situation. On November 19th, the Attorney General decided (HR), on the basis of Article 8 of the act implementing the EPPO Regulation, which transposes Article 25(6) of the Regulation, to take over the investigation from the EPPO with the following arguments. First, he explained that USKOK filed a proposal on the 15th of November asking him to resolve the conflict of competences with the EPPO in its benefit.

Second, it is explained in detail that the successful public procurement procedures brought damage to the Croatian budget of EUR 1 408 098, whereas the failed contract were to be financed by both the national budget and EU funds. Therefore, the USKOK concludes that no financial damage was incurred for the EU budget because the hospital director refused to accept the bribe offered and the minister did not receive the bribe he was promised for his assistance to secure the contract for the companies.

USKOK also claims it learned about the EPPO investigation from the district court in Zagreb and was not duly informed about it by the EPPO. It is also of the view that the EPPO does not have competences in this case because, first, Article 22(2) of the Regulation refers to a criminal organisation, as defined by Framework Decision 2008/841/JHA and as implemented in national law, if its objective was to commit the offences that are covered by the EPPO’s material competence. USKOK considers that the criminal organisation was established with the objective to commit offences against the national budget only. There are no indications that the criminal organisation had an objective to commit offences against the EU financial interests, it claims. Out of the five public procurement procedures only one involved EU funding, the USKOK’s proposal says.

The authority also relies on Article 25(3) of the Regulation, which requires the EPPO to refrain from exercising its competence when the maximum sanction in national law for an offence falling within the EPPO’s material scope is equal or less than the inextricably linked offence. The only exception is if the inextricably linked offence is instrumental to commit the offence covered by EPPO’s competences. National law envisages 12 years in prison for offering bribes in the framework of a criminal organisation, which is equal to the sanction for the inextricably linked offence of giving and receiving bribe. This means, USKOK claims, the EPPO must refrain from investigating. In addition, the potential damage for the EU financial interests is less than the damage for the national budget. In this respect, the EPPO is accused of infringing the principle of loyal cooperation.

In his argumentation, the Attorney General recalls that two fundamental principles inform the relationship between the EPPO and national authorities. Those are the principles of shared competences and the principle of loyal cooperation. He is convinced that, on this basis, the EPPO has a duty to inform the competent national authorities about offences that are not covered by its material competence. The Attorney General agrees with the argumentation provided by USKOK, concluding that the EPPO is not competent to investigate this case. From his explanatory note it seems the EPPO was not given the opportunity to present its own view.

Since this is an affair under development, the next section provides a brief analysis of the main claims by USKOK and the Attorney General, followed by a summary of the latest developments as reported by Croatian media.

Analysis

To summarise, the Croatian national authorities decided to take over the investigation on the basis of three main claims: the EU budget incurred no damage; the objective of the involved criminal organisation was not to damage the EU’s financial interests but the national budget; the sanctions for offences under the EPPO competences are equal or less to the inextricably linked offences in national law. The EPPO is accused also of infringing the principle of sincere cooperation by not informing the national authorities about offences not falling within its competences.

What does Regulation (EU) 2017/1939 say in such a situation? The evolution of the idea of the establishment of a European Public Prosecutor started from an exclusive competence, which was also the view of the European Commission in its Proposal for the establishment of an EPPO but, during the negotiations on the draft Regulation, the choice fell on shared competences. As Herrnfeld, among others, expected, this solution would lead to conflicts.

The material scope of the EPPO covers the offences listed in Directive (EU) 2017/1371 (the PIF Directive), as implemented by national law but notwithstanding how these offences are classified in national law. Thus, the EPPO is competent to investigate non-procurement-related expenditure, procurement-related expenditure, revenue other than revenue arising from VAT own resources, revenue arising from VAT own resources (Article 3 of the PIF Directive) and also money laundering, active and passive corruption (when there is intent), misappropriation (Article 4 of the PIF Directive).

In addition, the EPPO is competent when a criminal organisation is involved if its objective is to commit offences for which the EPPO is competent. The EPPO is also competent for the so-called inextricably linked offences, namely offences that are indivisibly linked to the conduct falling within the material scope of the EPPO. This is without prejudice to the exceptions in Article 25(3) of the Regulation, which restrains the EPPO from exercising its competence when the offence is for less than EUR 10 000 (Article 25(2) of the Regulation). The national authorities have a duty to not exercise their own competence if the EPPO had decided to exercise its own (Article 25(1) of the Regulation) by way of evocation (Article 27 of the Regulation).

From what has been made public so far, it is clear that the suspects intended to secure contracts in public procurement procedures for the delivery of high-tech medical equipment by offering bribes to the directors of hospitals and the former Minister of Healthcare. As per the statements by both the EPPO and USKOK, only the procedure for the hospital in Split was to be funded with money under the RRF but the director of that hospital refused the bribe and thus the contract failed. However, the promise of a bribe, suggesting intent, is not denied by either of the parties. The question then is whether the offence falling within the scope of the EPPO is preponderant.

Herrnfeld is of the view that the EPPO is not competent in cases when the damage to the EU’s financial interests is less than the damage to the national budget in this case. According to the EPPO statement, the value of the robotic equipment that was to be procured by the hospital in Split was of a value of almost EUR 5 million and was to be fully financed by the RRF. As to the other procurement contracts, the estimates of the Attorney General suggest a damage for the Croatian budget of EUR 1.4 million.

The project that were to be funded with EU funds is obviously preponderant but the question is whether it counts if the contract failed and no damage was incurred. The main issue here is the offering and acceptance of bribes. Article 4(2)(a) of the PIF Directive describes passive corruption as an offence when a public official accepts even a promise for a bribe because this creates a likelihood for damage to the EU financial interests. Article 4(2)(b) refers to active corruption which is described as an offence when an individual promises, offers or gives to a public official an advantage, which may affect the EU’s financial interests. This suggests that, even though the contract with the Split hospital failed, the promise was allegedly made and the minister, allegedly, accepted it.

The second claim in the decision to take over the investigation from the EPPO is that the objective of the criminal organisation was not to damage the EU’s financial interests but only the national ones. It would be interesting to see on what grounds USKOK and, subsequently, the Attorney General, were able to so neatly distinguish between the two objectives. Regretfully, with the publicly available information, it is hard to either confirm or reject this claim. However, the fact that a bribe was offered for a procurement procedure that was to be financed entirely from the RRF makes it less convincing.

The third claim is related to the size of the sanction for PIF offences and for inextricably linked offences, which is dealt with in Article 25(3)(a) of the EPPO Regulation. Herrnfeld provides a valuable background as to why this provision became necessary, namely to avoid a ne bis in idem situation in the presence of inextricably linked offences. In the case at hand, there are five public procurement procedures, one of which, it is claimed, involved EU funds, while the rest affected the national budget. In this way, the other four procedures could be considered as inextricably linked offences.

If this is the case, then the EPPO should be able to exercise its competences if the offence affecting the EU’s financial interests is preponderant, as Recital 55 of the EPPO Regulation explains in terms of gravity, which is to be measured by the size of the sanction. Recital 56, however, allows the possibility the EPPO to exercise its competences even when there is no preponderance but the inextricably linked offences are instrumental. This would be the case if the offences in the other four procedures were committed with the only idea to commit the one that affects the EU’s financial interests.

From the publicly available information, it can be inferred that the criminal organisation was after contracts with various hospitals, notwithstanding whether EU or national money was involved. It can hardly be inferred that the contracts with the other hospitals were instrumental for the realisation of the contract with the hospital in Split, thus this option cannot be used.

As to the claim of a failure to inform, the EPPO has a duty to inform the competent authorities about its decision to exercise or not its competences (Article 25(5) of the Regulation), a duty to inform the authority that reported the offence (Article 26(2) of the Regulation), and a duty to inform the competent national authorities about the launch of an investigation (Article 26(7) of the Regulation). However, the EPPO's internal rules of procedure allow for an exception if a European Delegated Prosecutor is concerned about the integrity of the investigation. In such a situation, they must inform the Permanent Chamber. It is the Chamber that can decide whether or not to inform the national authorities about the investigation (Article 41(4) of the internal rules).

What now?

Many scholars5 have warned that the ambiguity of Article 25 of the Regulation may lead to conflicts that can have the effect of violating the fundamental rights of the suspects and of slowing down the investigation, thus delaying justice and remedy for the victims. An interpretation by the Court of Justice may be helpful, as a first step, to untie the knot. Regretfully, the opportunity presented by the Ayuso case in Spain has not yet resulted in a reference for a preliminary ruling.

Many scholars5 have warned that the ambiguity of Article 25 of the Regulation may lead to conflicts that can have the effect of violating the fundamental rights of the suspects and of slowing down the investigation, thus delaying justice and remedy for the victims. An interpretation by the Court of Justice may be helpful, as a first step, to untie the knot. Regretfully, the opportunity presented by the Ayuso case in Spain has not yet resulted in a reference for a preliminary ruling.

In the meantime, opposition members in Croatia vowed to turn to the Constitutional Court with a question about the constitutionality of the act implementing the EPPO Regulation in Croatian law and with a request the CC to refer a question for a preliminary ruling to the Court of Justice pursuant to Article 267 TFEU. This will be another much needed opportunity to clarify who has competences in what situations and, hopefully, to find whether those Participating States that determined their attorney generals to be the national authorities to decide on conflicts of competences are infringing EU law.

There are two challenges for such a development. The first is whether the Croatian Constitutional Court would accept the task and would indeed refer a question to the Court of Justice. There have been accusations against it in the past of politicisation and bias towards the government. An additional challenge is that negotiations are currently under way to fill vacancies in the CC and to make appointments for judges whose term is about to end.

The second challenge is that even if a reference were sent to the CJEU and the Court did deliver a much needed judgment, this would not help much the obvious efforts of part of the Croatian judiciary to prevent rule of law backsliding by holding public officials accountable for corruption and abuse of office. Before the appointment of Attorney General Turudić, there was a good cooperation between USKOK and the EPPO and many public officials were held accountable. It is possible that this will no longer be the case.

A very concerning development is the initiation, by the Attorney General, of an investigation against those who may have leaked details about the investigation to the press. This is the first time the criminalising provision of the amended Criminal Law, also known as Lex AP (after the name of the prime minister) is applied. Coincidentally, the Attorney General announced the investigation a day after Prime Minister Plenković had a public outburst at the media publications where a lot of details about the suspects, their businesses and other information have been made public.

Lex AP was subject to protests earlier this year with journalists fearing that this amendment was aimed at them and their sources, thus effectively preventing investigative journalists from doing their job and also creating a chilling effect for whistleblowers.

In an unexpected development, the EPPO issued a statement revealing several very concerning issues. Initially, it planned to do searches and arrests on the 19th of November but it learned on the 15th that USKOK had obtained court orders in an investigation of which it failed to inform the EPPO pursuant to Article 24(2), (3) and (5) of the EPPO Regulation. This forced the EPPO to announce the investigation earlier.

Despite that the EPPO still considers it has competence, it decided to send the file to USKOK. In parallel, the European Chief Prosecutor sent a formal letter to the Commission, informing it of the ‘systemic challenges in upholding the rule of law, in line with Article 4 of Regulation (EU) 2020/2092 of 16 December 2020 on a general regime of conditionality for the protection of the budget of the European Union (Conditionality Regulation)’.

In addition, the ECP noted that the choice of the Croatian legislator to appoint the Attorney General as the national authority responsible to resolve conflicts of competence is not in line with EU law. Moreover, the ECP admits the EPPO was not given a chance to explain its position and the decision of the Attorney General to take over the investigation was based only on USKOK’s claims. Lastly, USKOK failed to inform the EPPO of its own investigation.

With all this in mind, it is of utmost importance the Commission to quickly assess whether the Participating States have properly implemented the EPPO Regulation and to launch infringement proceedings against those that have not. This would ensure that only a judicial authority would be given the powers to decide on conflicts of competence and that such decisions would be subject to judicial review, including by the Court of Justice.

To conclude, the latest developments in Croatia, which are not yet as severe as those in Slovakia, suggest that the way the EPPO Regulation is drafted, it depends entirely on the good will of the national authorities. Once the good will disappears, the EU’s financial interests, which are also the interests of the EU taxpayers, are no longer protected. In addition to that, the EPPO, as a supranational institution which was capable of empowering local actors to go against powerful politicians and businessmen, is deprived of powers, thus no longer able to help in the fight of the judiciary to protect its independence. Even though this was never the objective behind the establishment of the EPPO, the Croatian example shows this was a welcome side effect.

The European Chief Prosecutor, Laura Kövesi, repeated her calls for a revision of Regulation (EU) 2017/1939 during her first hearing in the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) after the European elections. Among her requests are the ambiguities in the Regulation to be clarified, the EPPO to receive an appropriate budget to enable it to do its work efficiently and effectively. She also asked for dedicated police investigators. This is very important not only in light of her statement that in a Member State police investigators are allowed to work on EPPO cases only 10 days per year (sic), but also regarding the current situation in Croatia, where media reported that it was possible information about the EPPO investigation to had been leaked to some of the suspects which enabled them to leave Croatia to evade prosecution.

With the speed with which governments that favour capture of the judiciary and work to prevent the EPPO from being effective in their countries, it is very important to start deliberations on amendments of the Regulation while it is still possible to push them through.

1 Nacional, Issue 1262, 28/06/2022

2 Hans-Holger Herrnfeld, Dominik Brodowski and Christoph Burchard, European Prosecutor’s Office, Article-by-Article Commentary (Hart Publishing 2021)

3 Marin Bonačić, ‘The European Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Croatian Criminal Justice: Implementation Requirements and Possible Solutions, Croatian Annual of Criminal Sciences and Practice’ (2020) 27 Croatian Annual of Criminal Sciences and Practice

4 Even though the legal basis of Regulation (EU) 2017/1939 is Article 86 TFEU, Article 325(1) TFEU, which codified the assimilation principle as developed in the Greek Maize case, also applies

5 Valsamis Mitsilegas, ‘European Prosecution between Cooperation and Integration: The European Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Rule of Law’ (2021) 28 Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law; Till Gut, ‘EPPO’s Material Competence and Its Exercise: A Critical Appraisal of the EPPO Regulation after the First Year of Operations’ (2023); Laura Neumann, ‘The EPPO’s Material Competence and the Misconception of “inextricably linked offences”, EuCLR Vol. 12, 3/2022