The End of the CVM: The Rule Of Law Mechanism Nobody Wants but Which the CJEU Made a Powerful Tool of

Adelina Marini, May 17, 2023

When Ursula von der Leyen said in her election speech in the European Parliament on 16th July 2019 that 'there can be no compromise when it comes to respecting the Rule of Law', it was a beam of hope that the EU had finally recognized that this was its most fundamental priority if it were to remain loyal to the Treaties, both to the spirit and the letter. Almost at the end of her term as Commission President, however, Ursula von der Leyen's legacy is all but an uncompromising respect for the Rule of Law.

When Ursula von der Leyen said in her election speech in the European Parliament on 16th July 2019 that 'there can be no compromise when it comes to respecting the Rule of Law', it was a beam of hope that the EU had finally recognized that this was its most fundamental priority if it were to remain loyal to the Treaties, both to the spirit and the letter. Almost at the end of her term as Commission President, however, Ursula von der Leyen's legacy is all but an uncompromising respect for the Rule of Law.

Examples of her Commission's selective approach in dealing with serious breaches of the rule of law have grown significantly in number and have attracted the attention of media and the academic community a lot, with one notable exception - the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM). This is one of the very neglected and understudied pieces of EU law, an important part of the rule-of-law toolbox, especially because of its direct link to EU accession. Moreover, it is one of the very illustrative examples of how Ursula von der Leyen betrayed the Parliament when she said in the above mentioned speech that her Commission would use all the tools available but, instead, her Commission has quietly stopped implementing the CVM, without even repealing it. The Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU, the Court), in a series of important judgments, has in the past few years attempted to correct this injustice by making the CVM a very powerful instrument in the fight to protect the rule of law.

How it started vs how it is going

On 22 November 2022, the European Commission adopted the last report on Romania under the CVM with a conclusion that Romania had fulfilled all the CVM benchmarks. The Commission also stated that it would no longer monitor rule of law developments under the CVM but under the general rule of law mechanism, the Annual Rule of Law Report (ARLR). This happens three years after the Commission reached the same conclusion on Bulgaria, in 2019.

However, as you may have noticed, there was no celebration, even though political elites and citizens in both countries impatiently awaited these decisions, hoping they would open the doors to Schengen and would finally remove the mark of second-hand citizens of the EU. One reason why there is no mood for celebration is that the CVM is not completely over. At least, not legally. And, it still haunts the two countries’ accession hopes for Schengen, as can be seen from the failed attempts by the Council Presidency to push through Romania's and Bulgaria's accession last year. Another reason is that the CVM is not a success and it is the Commission that shares a large part of the blame.

With both reports, the Commission committed to repeal the decisions on the establishment of the CVM only after consulting the European Parliament and the Council. However, without awaiting the two institutions’ feedback, the Commission ceased monitoring, thus, in fact, refusing to do its job under EU law. Both decisions have not yet been repealed and continue to be in force, thus leaving a legal vacuum, especially with regard to cases where the CVM has been used as a conditionality, such as Schengen or, in an informal way, EMU accession. This also raises important questions about the role of the Commission in applying the rule of law instruments and, more specifically, its own respect for the rule of law.

These actions of the Commission, as this article argues, are a bad news for the rule of law and mutual trust in the EU, and will, very likely, have a negative impact on future enlargements. The structure of this article is as follows. First, a brief recollection of what the CVM is and why it was adopted. Second, a detailed review of the current legal status of the CVM and the consultation process with the Council and the European Parliament. Third, before concluding, a comparison between the CVM and the ARLR, which is necessary because the Commission announced it would continue monitoring rule of law developments in Bulgaria and Romania under the ARLR framework.

What is the CVM and why does it exist?

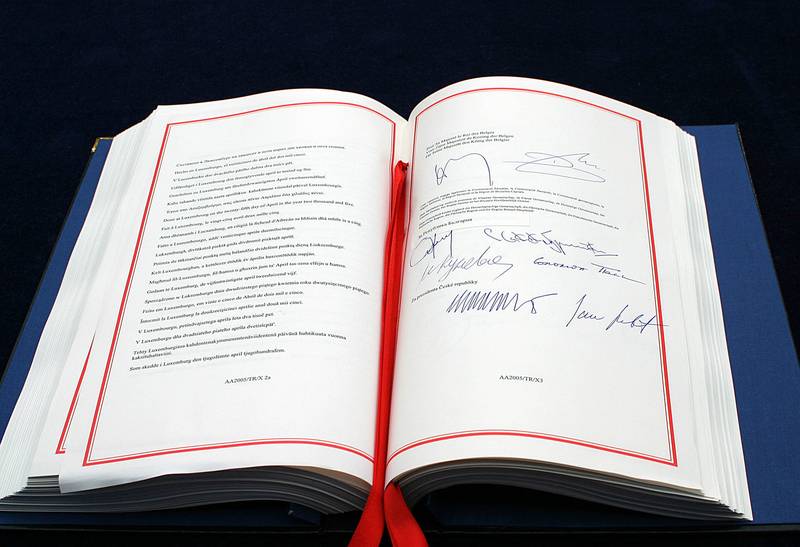

The CVM was established with Commission Decisions 2006/928/EC for Romania and 2006/929/EC for Bulgaria as a tool to allow the accession of the two countries to the EU without them having fulfilled all the necessary criteria in time for the planned date, 1 January 2007. As recital 6 of the said Decisions acknowledges, ‘the remaining issues in the accountability and efficiency of the judicial system and law enforcement bodies warrant the establishment of a mechanism for cooperation and verification of the progress of Bulgaria [and Romania] to address specific benchmarks in the areas of judicial reform and the fight against corruption and organised crime’. Or, as Advocate General Collins described it, in the third CVM case, C-817/21 RI, the CVM was established because of Romania’s failure (and Bulgaria's by analogy) to honour its pre-accession commitments (point 3 of AG Collins’s Opinion).

The legal basis for the adoption of the CVM Decisions is the Treaty of Accession of Bulgaria and Romania and, more specifically, Articles 37 and 38 of the Act of Accession. These two articles are related, respectively, to the functioning of the internal market and of the area of freedom, security and justice (AFSJ). The Decisions are addressed to all the Member States.

The annexes to the two Decisions contain the benchmarks the two Member States are obliged to fulfil before the CVM is closed. In the case of Bulgaria, the benchmarks are six and include, inter alia, constitutional amendments to ensure the independence and accountability of the judicial system; transparency and efficiency of the judicial process; professionalization, accountability and efficiency of the judiciary; investigating and prosecuting high-level corruption, with the borders and local government mentioned specifically in benchmark 5; and fighting organised crime. According to the annex, Bulgaria is expected to show a track record of indictments and convictions.

The benchmarks for Romania are four and involve, similarly, a transparent and efficient judicial process, accountability, integrity; professional and non-partisan investigations of high-level corruption; fighting corruption, especially within the local government.

In its first ever judgment on the CVM (the AFJR joined cases), the CJEU declared the Decisions, including the benchmarks, legally binding pursuant to Article 288(4) TFEU. Moreover, the Court said that the benchmarks ‘give concrete expressions to the specific commitments undertaken by Romania and the requirements accepted by it at the conclusion of the accession negotiations on 14 December 2004’ (paragraph 170), thus confirming the link with Article 49 TEU, on which the Court commented explicitly in paragraph 160 of the judgment. In addition, the Court stated that the Decisions remain binding until repealed, which is important for the analysis of the Commission’s implementation of EU law to be discussed later in this article.

The Decisions obligate the Commission to report to the Council and the European Parliament on the progress of the two countries in the implementation of the benchmarks every six months (at least) (Article 2 of the Decisions). Until 2012, the Commission did indeed report twice per year. After that, however, the Commission started reporting, with some deviations due to specific circumstances, once per year. In 2019, it ceased reporting on Bulgaria. On Romania, it reported in 2021 and finally in 2022.

The reports are organised in two parts: a technical and a progress report (also known as a political report). The former is prepared as a staff working document, which contains the analysis of work done under each of the benchmarks focusing on adopted legislation, ongoing work, progress/regress. It is prepared by Commission staff on the ground, by consulting various institutions and actors, including non-governmental organizations, opposition members. It should be noted, however, that the Commission did not publish a technical report for Romania in 2021 and 2022. It is probably possible to request it via the access to information act. It is not the first time the Commission failed to publish a technical report. It happened in 2012 and 2016 (they are now available) as well but upon a request the reports can be obtained.

The political part contains a summary of progress and its purpose is to communicate the Commission’s views on progress. The reason why this part is called political is not only that the Commission uses it to convey specific messages either to the other Member States and the Parliament or to specific audiences in Bulgaria and Romania, but also because of the way these parts of the report are adopted. In the beginning of the CVM, the reports were approved in the College via the so-called oral procedure, which means that the texts were subject to discussions among the Commissioners. Subsequently, the adoption of the reports was changed to written procedure, which eliminated debates in the College. The texts of the political parts were also subject to intensive consultations with the governments of Bulgaria and Romania in the Ad Hoc Working Party on the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism within the Council.

The CVM has been heavily criticised in the academic literature, albeit for different reasons. In political science, it is viewed predominantly as a post-accession conditionality instrument criticised for being badly constructed by the Commission and for not being efficient. There is a majority of scholars who consider the CVM a failure (Dimitrov et al., 2013(1); Toneva-Metodieva, 2014(2); Sedelmeier & Lacatus, 2017(3)). In legal science, the CVM is viewed as a rule of law instrument, mentioned often only occasionally, as being with a very limited coverage (Pech, 2022(4); von Bogdandy & Ioannidis, 2014(5)). There are also criticisms of it being unfair for creating inequality between the CVM countries and the other EU Member States (Dimitrovs & Kochenov, 2021(6)).

The overall atmosphere reveals a feeling of exhaustion and that the CVM belongs to the past. Indeed, after more than a decade of experience, a sort of fatigue has emerged, both in Bulgaria and Romania and within the Commission, from the exercise which has developed over the years a highly politicized character. The culmination of the politicization of the CVM was Jean-Claude Juncker’s speech at a party gathering in Sofia on 27 April 2014, where, in his role as a Spitzenkandidat of the European People's Party (EPP) for the Commission presidency, he committed to ending the CVM for Bulgaria by the end of his term.

As promised, in the end of his term, the Commission adopted the final CVM report on Bulgaria with a conclusion that it had implemented all the benchmarks. Juncker’s Commission thus left it to his successor to decide either to repeal the Decisions or to continue monitoring. Ursula von der Leyen’s Commission chose a path in-between – it neither repealed the Decisions nor did it continue monitoring, even though the Court said explicitly that the CVM continues to produce legal effects until it is repealed (Euro Box Promotion and Others, paragraph 165).

An aspect never addressed in the literature on the CVM, but which is very important for the understanding of its legal value, concerns its relation with regard to other instruments. The CVM raises the following questions: Is there automaticity in the application of the conditionality mechanisms? This question is particularly relevant in view of Regulation 2020/292 on a general regime of conditionality for the protection of the Union budget (the rule of law conditionality) because, as article 4 of that Regulation states, the lack of effective judicial review of independent courts, prevention and sanctioning of corruption and fraud are considered breaches of the rule of law and therefore can be subject to applying the Regulation. Should not, therefore, due to its very existence, the CVM be a sufficient ground to apply the rule of law conditionality automatically?

While it is not the purpose of this article to answer these questions, some potential answers do emerge later in the article in the opinion of the European Parliament and in the case law. In addition, these questions are important to better understand the CVM's legal value and have them in mind for future investigations.

Another important question is related to the European Arrest Warrant (EAW). The CJEU has developed an already solid line of cases related to the EAW, where national courts express doubts whether it is safe to extradite a person to a Member State which is in a process of rule of law backsliding. According to one of the seminal cases in this line, the LM judgment, the Court allowed the possibility a national court to refuse to implement a EAW request if there are ‘systemic deficiencies’ in the requesting Member State. With the CVM being in force, does it mean that the same logic applies?

The CJEU has built its reasoning in this line of cases around the principle of mutual trust, which is an essential part of the CVM. In recital 2, the CVM Decisions note that the AFSJ and the internal market ‘are based on the mutual confidence that the administrative and judicial decisions and practices of all Member States fully respect the rule of law’.

As Kim Lane Scheppele, Dimitry Kochenov and Barbara Grabowska-Moroz write(7), the availability of independent courts is crucial for the efficient functioning of the EAW and the mutual recognition of judicial decisions. If this fails, the whole ‘edifice of mutual trust is endangered’. The President of the CJEU, Koen Lenaerts, stressed similarly in a speech(8) in Sofia that, in the context of the EAW, ‘only an independent court may guarantee that the judicial decision to be recognised and enforced was adopted in keeping with the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Charter’. Most judgments in this line of EAW case law concern Poland and Hungary but it begs the question whether their logic can be applied mutatis mutandis to situations of judicial independence never built properly in CVM countries? Again, it is not the objective of this article to answer these questions, but asking them helps better understand the legal value of the CVM.

What is the current legal status of the CVM?

The short answer is that it is still good law and, as the Court stated, it still produces effects which means that, since the Court declared that the CVM has direct effect (AFJR, paragraph 249), various actors in Bulgaria and Romania can challenge different aspects of the judiciaries of those Member States as being incompatible with the CVM. As the growing line of CVM cases from Romania suggests, there are plenty of possibilities. The first CVM case, the AFJR joined cases, comprises five cases initiated by NGOs and/or individuals. One of them, for example, is related to the transparency of the judiciary. What was challenged was the refusal of the Judicial Inspectorate of Romania to disclose statistical information regarding the number of initiated disciplinary proceedings.

Another case is related to the legality of the disciplinary regime within the Public Prosecutor’s Office. This one makes it a very good candidate to compare with the legal battles of the Commission over rule of law backsliding in Poland and the advantages of the CVM over a more general rule of law regime. Other cases in the line include abuse of office of prosecutors, the accountability of inspectors (C-817/21 RI), high-level corruption and protection of high-level officials by the Constitutional Court (Euro Box Promotion and Others), etc. This is possible because, as AG Bobek said in his AFJR Opinion, the CVM allows for an abstract review of certain models without a specific infringement of EU law because the CVM is EU law and everything that it covers can be considered implementation of EU law. This entails that the Charter also applies, thus opening vast opportunities for litigation and, consequently, rule of law protection.

A longer answer, however, goes beyond the national context of the CVM countries and involves the overall context of the rule of law crisis in the EU. Even though many scholars depicted the CVM as an instrument with very limited scope (Bulgaria and Romania only), it is worth recalling that the CVM Decisions are addressed to all the Member States as they are the main EU accession stakeholders. The Commission is also accountable to the Council and to the European Parliament. And this is even before starting to consider it as an accession instrument, which may have positive or negative consequences for future EU enlargments but is mostly relevant for the mutual trust within the EU - a fundamental concept, which much of EU law depends on, as the EAW line of cases illustrates. This opens the possibility the CVM to be called not only a rule of law instrument but a mutual trust instrument as well.

While concluding that Bulgaria and Romania have implemented all the benchmarks, the Commission stated clearly that it would repeal the Decisions only after considering the observations of the Council and of the European Parliament. In October 2020, the European Parliament adopted a very detailed resolution in which it strongly disagreed with the conclusions of the Commission, citing reports by the Commission itself under the European Semester, reports by other EU institutions, such as OLAF, of various organizations, such as the OSCE, the Venice Commission, and ECtHR case law. According to the resolution, not only was there no progress in Bulgaria, but the situation with the rule of law and democracy had deteriorated in the past years.

The resolution also noted that Bulgaria still lacked a track record of convictions of high-level corruption cases, as required by the CVM benchmarks (Benchmark 6), and concluded that the problems in Bulgaria are systemic, which, again, raises the question of the automaticity vis-à-vis other EU rule of law instruments if the logic of the EAW case law is applied. The Court explained in the LM judgment that if there is a ‘real risk, connected with a lack of independence of the courts of that Member State on account of systemic or generalised deficiencies there, of the fundamental right to a fair trial being breached’ (paragraph 61). The CVM never served this purpose, though. It was only used to block Bulgaria's and Romania's Schengen accession.

The Parliament urged the Commission to continue monitoring under the CVM but opened the possibility for replacing it with the ARLR. In addition, the Parliament called on the Commission to not be shy and use all other rule-of-law instruments, such as infringement procedures, suspension of funds (at the time of the adoption of the resolution, the rule of law conditionality had not yet been adopted) but there are other types of conditionalities throughout various EU law instruments. A very good overview of how this can be done, by Kim Lane Scheppelle and John Morijn, can be found here. The resolution is the first time sanctioning CVM countries under the rule of law conditionality is implied. It follows that the European Parliament disagrees with the Commission’s finding that the CVM benchmarks have been implemented.

As to the Council, it has been so far unable to reach a common position. At the first meeting of the Ad Hoc CVM working party in the Council, after the Commission sent its proposal to close the CVM, the draft conclusions contained an invitation to the Commission to continue working under the CVM. The second meeting ended with the same conclusions, while, at the last meeting, the draft conclusions expressed readiness to conclude the CVM. However, final conclusions have not yet been adopted. According to a document by the Council Presidency, there were several Member States that insisted that the CVM was still in force and expressed expectation the Commission to continue its monitoring activities.

After the Commission sent its proposal to end the CVM for Romania, the situation remains very much the same in the Council. With regard to Romania, one Member State insisted that all benchmarks must be fulfilled ‘in an irreversible and sustainable manner’ before the CVM is repealed, which reveals disagreement with the Commission's conclusions that all the benchmarks are fully met. Another Member State is reported to have said that the CVM ‘serves a different purpose than the Commission’s rule of law report’, thus expressing disagreement with the Commission to continue monitoring under the ARLR.

With regard to Bulgaria, the Presidency reported that two Member States maintain their positions from 2021. A third Member State urged the Commission to continue reporting on progress under the CVM ‘until the formal repeal of the decision establishing the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism’. Thus, it can be concluded that there is no consensus yet in the Council to end the CVM. It follows that neither the Council nor the European Parliament were able to produce an unequivocal approval of the Commission's proposal to end the CVM, which probably explains why it has not been repealed it yet. It does not explain, however, why the Commission has stopped implementing it despite not having received the approval of the two institutions and despite the Court's judgments stating that the CVM produces effects until repealed.

Now that we have established what the CVM is and that it is still in force, it is time to compare it with the ARLR in order to see whether it is a good replacement.

The difference between the CVM and the ARLR

Unlike the CVM, which is hard law by way of being a Commission Decision pursuant to Article 288(4) TFEU, binding in its entirety and having direct effect, the ARLR is a soft law instrument, which is not legally binding and does not have direct effect. Before last year, it did not contain any recommendations but even with recommendations, its force remains very soft and very far from the 'special position' of the CVM recommendations, as articulated by AG Bobek.

As discussed above, despite the justified criticism of the inefficiency of its application, the CJEU case law has revealed that the CVM is a powerful instrument, which can be used as a channel to defend the independence of the judiciary and fundamental rights on national level. As AG Bobek explains in the AFJR case, the CVM Member States ‘are in a specific position’, which means that there are ‘ample primary, as well as secondary, law bases to examine any aspect of their judicial structure, provided that it can be said to relate directly to the yardsticks and conditions set out in the CVM Decision and the Act of Accession’. This is what makes it much more powerful than the instruments currently available and being employed by the Commission against Hungary and Poland.

Moreover, as suggested by AG Collins, the CVM allows the Commission to use infringement proceedings when its recommendations are disregarded. In his Opinion in Case C-817/21 RI, in point 36, AG Collins noted that the Commission did not bring infringement proceedings against Romania’s non-compliance with the recommendations in the 2021 CVM report. For its part, Romania does not seem to have addressed those recommendations, the AG said.

This is more than a statement of facts. The AG seems to clearly expect the Commission to apply other instruments when a CVM country fails to comply with its recommendations which, even though not legally binding, the Court said that Romania (and, by analogy Bulgaria) has an obligation to take them into account (paragraph 177 of the AFJR judgment). This may serve as an answer to the question of the CVM automaticity.

As AG Bobek explained in his Opinion in the AFJR cases, the recommendations in the reports ‘give specific expression to the benchmarks’ (point 160 of his Opinion). Following this logic, it can be concluded that the Commission also has an obligation to follow up on its own reporting, as AG Collins suggested in his Opinion. This is a significant development, since until now the Commission stayed on high ground, avoiding getting the attention for the poor implementation of the CVM. The combined reading of all the CVM judgments and opinions so far reveals an obligation by the Commission not only to continue reporting until Decisions 2006/928/EC and 2006/929/EC are repealed, but also to follow up on whether its recommendations are duly taken into account and, if not, to undertake other measures, including triggering the rule of law conditionality or other funding conditionalities currently available.

The ARLR, conversely, is established to ‘prevent problems from emerging or deepening’. Problems did not emerge in Bulgaria and Romania. They joined the EU with these problems. The ARLR's main objective is only to ‘improve understanding and awareness’. It leaves any solutions in the hands of the Member States. It lacks a sanctioning mechanism and does not empower national courts to defend themselves against anti-rule-of-law political forces, nor does it provide a direct effect to allow individuals to defend their own rights. Therefore, the very different legal power of the ARLR makes it an inappropriate replacement for the CVM. Furthermore, it is also what President von der Leyen promised not to do in her speech from 16th of July 2019 to the European Parliament: "To be clear: the new instrument [the ARLR] is not an alternative to the existing instruments, but an additional one." And yet, her Commission is using the ARLR as an alternative to an existing instrument, the CVM.

It is important to stress further that, by setting the CVM aside, the Commission leaves an area of the rule of law crisis in the EU unaddressed. That is not the area of rule of law backsliding but the area of Member States that joined with underdeveloped rule of law and failed to develop it despite commitments. This is a rule of law area that is directly linked to EU accession. It is indeed true that in the already numerous Polish rule-of-law cases, the CJEU did make a reference to pre-accession commitments via Article 49 TEU. However, via the CVM and its legal basis, the link with pre-accession commitments is direct and immediate.

The CJEU has reminded on several occasions of the commitment Article 49 TEU contains, meaning that a conditionality is, in essence, a guarantee that the promise made before accession would be fulfilled. As the Court said, ‘the purpose of establishing the CVM and setting the benchmarks was to complete Romania’s accession to the European Union, in order to remedy the deficiencies identified by the Commission in those areas prior to that Accession’ (para 171 of the AFJR judgment). If this were not the case, a Member State can cheat its way into the EU without having fulfilled the criteria, if only it is patient enough to wait until the priorities change. As AG Bobek states in his AFJR Opinion, ‘the role of the CVM in the accession process was crucial within that context [of Articles 2 and 49 TEU]’. According to him, were the CVM Decisions and benchmarks not legally binding, this would have meant to give those countries ‘a carte blanche not to comply with the core requirements of Accession’ (point 153 of AG Bobek’s Opinion).

meaning that a conditionality is, in essence, a guarantee that the promise made before accession would be fulfilled. As the Court said, ‘the purpose of establishing the CVM and setting the benchmarks was to complete Romania’s accession to the European Union, in order to remedy the deficiencies identified by the Commission in those areas prior to that Accession’ (para 171 of the AFJR judgment). If this were not the case, a Member State can cheat its way into the EU without having fulfilled the criteria, if only it is patient enough to wait until the priorities change. As AG Bobek states in his AFJR Opinion, ‘the role of the CVM in the accession process was crucial within that context [of Articles 2 and 49 TEU]’. According to him, were the CVM Decisions and benchmarks not legally binding, this would have meant to give those countries ‘a carte blanche not to comply with the core requirements of Accession’ (point 153 of AG Bobek’s Opinion).

By quietly abandoning the CVM, the Commission is setting an example that a conditionality would fade away on its own due to reform fatigue or any other argument used by those who want to achieve swift political results at the expense of substantive reforms that would benefit the entire community and, most of all, citizens. This also means that the Member States that were convinced to drop their vetoes, to allow Bulgaria and Romania join with a CVM, were misled. By silently replacing the hard law CVM with the soft law ARLR, the Commission is removing a conditionality without the consent of the main stakeholders of EU accession – the Member States, which are the addressee of Decisions 2006/928/EC and 2006/929/EC.

Concluding remarks

To conclude, the CVM Decisions have not yet been repealed and, therefore, remain good law. The Commission is obliged by them to report at least twice a year on progress made and to apply all other available instruments that would help/force Romania and Bulgaria to implement the benchmarks. Such a conclusion is even more pressing in light of the mistrust some Member States (and the European Parliament) express in the Commission regarding the CVM. One Member State emphasised on the need not only all the benchmarks to be fully implemented but this to be ‘in an irreversible and sustainable manner’. This implies that the CVM is expected to stay longer than the Commission or other Member States would like. It should take as long as mutual trust is established because this is also a mutual trust instrument.

The CVM should not be viewed as a side gig that concerns only two Member States, but as a full-fledged rule of law instrument that empowers citizens and institutions. The CJEU's CVM case law may even make one think how good it would have been if Poland and Hungary had the CVM because it would have been sufficient to address much more rule of law problems than is currently possible. As mentioned above, the CVM can be used in the abstract, which turns it into a powerful instrument to defend the rule of law.

If the CVM is implemented properly, with all the justified criticisms addressed, it may turn into a good solution also for future enlargement. The issue of enlargement may have been considered irrelevant only 2 years ago, when the EU was still stuck with the lack of progress in the Western Balkans and the difficult to define status of Turkey. After Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia filed applications for accessions in the spring of 2022, the issue has returned with a bang on EU's agenda.

The force of return of enlargement as a geopolitical challenge for the EU has been strongly enhanced by the numerous statements coming from various corners in the EU that Ukraine is fighting for the EU values, which is the very essence of Article 49 TEU: "Any European State which respects the values referred to in Article 2 and is committed to promoting them may apply to become a member of the Union". Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia's applications brought new life into Article 49 TEU and thanks to the CJEU case law, the CVM may be holding the key.

But before that, the Commission must be made aware of its own responsibility and forced to take it. It should not be allowed any more to apply EU law only when it serves its own political goals. The upcoming European elections may be a good opportunity to take stock of what President von der Leyen promised in her election speech in July 2019 and what she delivered before making the petty party calculations about the next Commission president.

References

Case law:

Joined Cases C‑83/19, C‑127/19, C‑195/19, C‑291/19, C‑355/19 and C‑397/19, Asociaţia ‘Forumul Judecătorilor din România’ [2021], ECLI:EU:C:2021:393

Joined Cases C-357/19, C-379/19, C-547/19, C-811/19 and C-840/19, Euro Box Promotion and Others [2021], ECLI:EU:C:2021:1034

Case C-216/18 PPU, Minister for Justice and Equality (Deficiencies in the system of justice) [2018], ECLI:EU:C:2018:586

Case C-817/21, Opinion, R.I. v Inspecţia Judiciară and N.L. [2023], ECLI:EU:C:2023:55

Academic sources:

(1) Dimitrov, G. et al., The Cooperation and Verification Mechanism: Shared Political Irresponsibility between the European Commission and the Bulgarian Governments (2013), Kliment Ohridski University Press

(2) Toneva-Metodieva, L., Beyond the Carrots and Sticks Paradigm: Rethinking the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism Experience of Bulgaria and Romania, Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 2014 Vol. 15, No. 4, 534–551

(3) Sedelmeier, U., Lacatus, C., Post-accession Compliance with the EU’s Anti-Corruption Conditions in the ‘Cooperation and Verification Mechanism’: Bite without Teeth? (2017), LSE

(4) Pech, Laurent (2022), The Rule of Law as a Well-Established and Well-Defined Principle of EU Law, Hague Journal on the Rule of Law

(5) Von Bogdandy, Armin, Ioannidis, Michael, Systemic Deficiency in the Rule of Law: What It Is, What Has Been Done, What Can Be Done, Common Market Law Review 51: 59-96, 2014

(6) Dimitrovs, Aleksejs and Kochenov, Dimitry, Of Jupiters and Bulls: The Cooperation and Verification Mechanism as a Redundant Special Regime of the Rule of Law, EU Law Live, June 5 2021, No. 61

(7) Scheppelle, Kim Lane, Kochenov Dimitry, Gabrowska-Moroz, Barbara (2020), EU Values Are Law, after All: Enforcing EU Values through Systemic Infringement Actions by the European Commission and the Member States of the European Union, Yearbook of European Law, Vol. 39, No. 1 (2020), pp. 3-121

(8) Lenaerts, Koen (17 February 2023), The Rule of Law and the Constitutional Identity of the European Union

Entrance to the Berlaymont building | © EC - Audiovisual Service

Entrance to the Berlaymont building | © EC - Audiovisual Service | © European Union 2020, EC - Audiovisual Service

| © European Union 2020, EC - Audiovisual Service Sergey Stanishev, Tsetska Tsacheva | © EP

Sergey Stanishev, Tsetska Tsacheva | © EP