The European Unity against Russia Has Its Limits

Adelina Marini, February 6, 2015

What could be heard very often last week after the extraordinary foreign affairs council of the EU was "unity". However, under the surface it becomes clear that this unity has limits. At the extraordinary meeting of the EU foreign ministers, called on the occasion of the deteriorating situation in eastern Ukraine and more specifically the rocket attacks in Mariupol, it was possible to see very clearly where the border of unity in EU lies. That border has been revealed with the different interpretation of the European Council conclusions from March last year regarding what could trigger new sanctions against Russia. The foreign affairs council from 29 January, although not saying much in its conclusions, in fact says a lot about how difficult the task to reach unanimity among the 28 member states is for common actions against Putin's aggression.

What could be heard very often last week after the extraordinary foreign affairs council of the EU was "unity". However, under the surface it becomes clear that this unity has limits. At the extraordinary meeting of the EU foreign ministers, called on the occasion of the deteriorating situation in eastern Ukraine and more specifically the rocket attacks in Mariupol, it was possible to see very clearly where the border of unity in EU lies. That border has been revealed with the different interpretation of the European Council conclusions from March last year regarding what could trigger new sanctions against Russia. The foreign affairs council from 29 January, although not saying much in its conclusions, in fact says a lot about how difficult the task to reach unanimity among the 28 member states is for common actions against Putin's aggression.

Last year, after Russia annexed the Ukrainian peninsula Crimea, the leaders of the member states agreed during their spring summit that "any further steps by the Russian Federation to destabilise the situation in Ukraine would lead to additional and far reaching consequences for relations in a broad range of economic areas between the European Union and its Member States, on the one hand, and the Russian Federation, on the other hand". Since then, there were two serious cases that could have been interpreted as "further steps" to destabilise by Russia. Those are the gunning down of flight MH17 over Ukraine in the summer and the rocket attacks in Mariupol in January.

The gunning down of MH17, which killed almost 200 people, failed to lead to expansion of the range of the economic sanctions against Russia but only to the inclusion of new persons to the EU black list. The attacks in Mariupol, in which tens of civilians died, also seems unable to achieve this. From the statement of the EU High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy Federica Mogherini after the end of the several-hour long meeting on 29 January it becomes clear that the meeting was demanded by several member states in agreement with European Council President Donald Tusk and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, "to not only assess the situation on the ground that is extremely worrying and negative, but also to decide on our reaction to that. And on the further steps to be taken at the European Union level", said Italy's former top diplomat.

The outcome of the meeting, however, reveals how strong the division in the EU is in terms of the perception of Russia and its actions. To some it is an aggressor, to others it is simply a trade partner who has gone crazy for a bit and a third group prefer to stay neutral. Against the background of the emotional statements about a really strong consensus and constructivism, the product of the meeting shows quite the opposite. The consensus is lacking and that is why the difficult decision for further measures is left for later. The Council strongly condemns, as all the previous times, the developments in eastern Ukraine and in order not to seem that it has no teeth the council decided to extend the agreed in March last year economic sanctions with another six months. In addition, the ministers agreed at their next meeting on 9 February to approve an updated ban list.

The reason is that to some the attacks in Mariupol are a sufficient reason to expand the range of sanctions, while to others it is not. Lithuania's Foreign Minister Linas Linkevicius, who usually speaks the strongest and the clearest on the issue, said that the developments in Mariupol are exactly the case that represents further steps to destabilise the situation. He went even further asking "how many people have to die before we all say Je suis Ukrainian?". UK's state minister for Foreign Office David Lidington shares the same opinion. "The loss of life that we saw in Mariupol was the worst loss of life, with the single exception of MH17, that we have seen throughout this conflict", he said and added: "It is the EU duty to prepare options for the future including, I think it's now necessary, the possibility of further restrictive measures".

However, Italy's Foreign Minister Paolo Gentiloni did not at all share that opinion. He said before the meeting that the ministers should not haste with new sanctions and after the meeting, at a briefing for the Italian journalists in Brussels he added that Italy defended the position that it is too early to undertake new sanctions in other economic sectors. According to him, a justification for new sanctions could be a direct Russian military interference in Ukraine, not just indirect. The news about the lack of unity among the 28 foreign minsters was practically stolen by Greece which dominated the media attention before and after the meeting because of the first reaction of the new Greek government against the EU statement about the attacks in Mariupol. The reason was that the EU did not request the agreement of the new government in advance. Greece has always had good relations with Russia but after the convincing victory of the far left party SYRIZA, the fears that Russia will have another Trojan horse in the EU have grown. After the passions subsided, it became clear that Greece is neither the biggest problem for the European unity toward Russia nor is it the only one.

Bulgaria wants to make an omelette without breaking the eggs

The extraordinary council of the EU foreign ministers confirmed that the current government of Bulgaria is strongly pro-European. A well informed source from the Bulgarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs told euinside that Bulgaria will support new sanctions against Russia if it comes to that in order not to destroy the consensus. Bulgaria is one of the most vulnerable member states. This is one of the reasons why it sends mixed signals. It both wants to be pro-European, which means to defend common European positions, but on the other hand Prime Minister Boyko Borissov said many times that the country is very dependent economically on Russia. At the December EU summit he said that he does not view Russia as a strategic problem and explained that Bulgaria is suffering from the economic sanctions much more than Russia itself.

But Bulgaria is one of the countries that support the establishment of a European medium in Russian which is to "correct" the Kremlin misinformation and propaganda. This has emerged another issue which failed to gather sufficient unity among the ministers. The idea of the foreign ministers of Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania and UK to undertake a decisive response to the Russian propaganda is welcomed coldly but it is a good sign that there is a consensus to work on "improving the strategic communication". At their extraordinary meeting, the ministers have given a mandate to highrep Mogherini to work together with the European institutions and the member states on the creation of a special team for the new strategic communication. The main task of this team will be "proactive communication of EU policies, correcting misinformation when it appears, and support for the further development of independent media throughout the region".

There is no doubt that the very fact that there is a consensus to work in this direction is a good news. The problem is, however, what will be the final result. Italy's Foreign Minister Gentiloni said quite directly that the Russian media have influence only on a minority of countries. I understand the sensitivity of the Baltic states, he said, but in Italy the Russian propaganda is not a big threat. It is, however, a problem not only for the Baltic states but for the entire eastern periphery of the EU and for the countries in the post-Soviet space. Russia will dominate the EU summit on 12 February. Moscow has already signalled that new sanctions on behalf of the EU would be a mistake which is a direct threat that Russia will retaliate.

It is worth noting, however, that the most vulnerable countries are the most unanimous that Russia must be stopped even if the price is severe economic consequences. It has to be clear, though, that when you have a dictator against you it is hard to talk about right decisions. Whatever you do or not do could have heavy consequences. But it is important the EU not to betray its values and purpose which sometimes cost dearly. But after all, it is easy to stick to your values in peaceful times. The big test is to defend them in turbulent periods.

Boyko Borissov, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU

Boyko Borissov, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU Boris Johnson | © Council of the EU

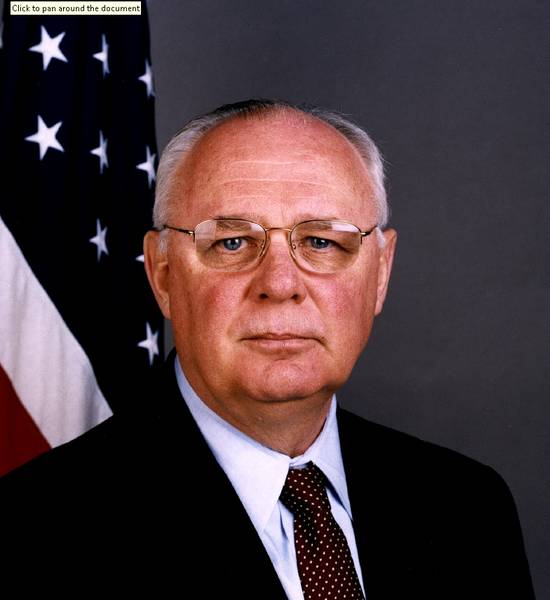

Boris Johnson | © Council of the EU James W. Pardew | ©

James W. Pardew | ©