#EP2014: Two Parallel Worlds

Adelina Marini, May 27, 2014

The European Parliament elections this year, for the first time, moved in two speeds. One was the traditional national campaigns and the other was the common European election campaign. The overlap between the two speeds was small and sporadic which, again, revealed the big controversy of the EU - it is both a union of sovereign states and has a life of its own, but both are in a growingly ruthless competition. That is why the stakes this time were for more or less Europe. In some member states, indeed, this was a major issue the answer to which was rather negative but in a prevailing number of member countries the issues were purely national with no attention at all for the common EU topics.

The European Parliament elections this year, for the first time, moved in two speeds. One was the traditional national campaigns and the other was the common European election campaign. The overlap between the two speeds was small and sporadic which, again, revealed the big controversy of the EU - it is both a union of sovereign states and has a life of its own, but both are in a growingly ruthless competition. That is why the stakes this time were for more or less Europe. In some member states, indeed, this was a major issue the answer to which was rather negative but in a prevailing number of member countries the issues were purely national with no attention at all for the common EU topics.

The great magic failed this time

The Lisbon treaty was planned as a European constitution, but because of prevailing nationalistic views it turned into an odd eunuch which both delivers and does not deliver. On the one hand, the Treaty provides for the creation of common European politics, but on the other - it cuts its wings at the very the roots. The European political parties got the chance to nominate candidates of their own for the European Commission's presidential seat, but the final word belongs to the European Council (the member states) which is not obliged in any way to accept the candidate of the winning party. The European Parliament and the European Commission worked hard to squeeze the maximum out of the quite stream-lined formulation in the Lisbon Treaty by passing an amendment to the legislation on the European political parties, thus proclaiming them as precisely this - parties. The Parliament proposed, after the initiative of British MEP Andrew Duff from the Liberal group, the creation of a transnational European list, but the initiative was left hanging in the air, completely ignored by the heads of state or government.

The irony is that Andrew Duff has lost his seat in the European Parliament, which he held for years, to the benefit of Nigel Farage's anti-European party - United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP).

In September, the European Parliament has launched the election campaign with the great ambition to make these elections different. Two were the main goals of the campaign. One was to make voters feel European citizens and go out to vote, thus putting an end to the durable trend of falling voter turnout. The second goal was to put an end to the domination of the Council which has become growingly intolerant to the community method and started seeking intergovernmental agreements which, practically, avoid the European Parliament's control and make that institution completely useless. The first goal has been achieved to a certain extent. The voter turnout has frozen at the 2009 level with an insignificant increase. Will the second goal be achieved we will find out today (May 27th) when the leaders of the member states gather in Brussels for an informal dinner (which means completely out of sight for the public) to discuss the outcome of the elections and to decide whether they should take them into account.

And the outcome deserves discussion. The parties with the biggest number of seats in the European Parliament, again, is the European People's Party (EPP) which, although registering a significant loss of MEPs, will have 213 representatives. Second come the Socialists and Democrats with 190 seats. The third force, again, but significantly withdrawn, are the Liberals who can rely on 64 MEPs, followed closely by the Greens with 52. All predictions of an invasion of eurosceptic, anti-European, xenophobic and even fascist parties have come true, but it is still too early to say what will be the distribution of their numbers in groups. The European Conservatives and Reformists, where a major power are David Cameron's Tories, also registered a loss and will have 46 deputies and the group Europe of Freedom and Democracy of Nigel Farage will have 38 members. The far left gets 42 people.  The uncertainty comes from the fact that the number of independents (non-attached) has increased from 27 in the past term to 41 (all numbers are still a subject to change).

The uncertainty comes from the fact that the number of independents (non-attached) has increased from 27 in the past term to 41 (all numbers are still a subject to change).

The Parliament enter also 63 people who are in the group "Others", which means that it is not clear which group they will join. The very grouping is not that important because what matters is how will the "free electrons" vote on key legislation like, for instance, deepening of the integration in the euro area or the EU enlargement toward new members. The candidates of the European political families for the post of European Commission chief have done a lot to bring the European election campaign into the national context, but it is very hard to assess to what extent has this succeeded. They held debates, only one round of which was broadcast on national TV stations, though not in all member states. There was a debate which was broadcast in the Euranet radio network. The rest were broadcast on pan-European media or online. However, in most of the debates Alexis Tsipras, the far right candidate, did not take part, whose party Syriza scored a comfortable victory in Greece.

National campaigns, though, have proved weakly pervious to the European agenda and invested all their resources in narrow domestic issues. In some cases, like in France, UK, The Netherlands and Denmark, where the Farage-type parties have turned into key political factors and even in leading political forces, the national campaigns were entirely about pro- or anti-EU. This has raised very seriously the issue about balancing - was the different position heard sufficiently well, which is the common European politics. The answer up to date is no, but the question needs a much deeper analysis. In this regard, the magic "common European politics" did not work. There was a brilliant election campaign, with a real competition of ideas about the future of the EU, which even overleapt the possibilities of the Commission as set in the Treaty, but people voted en masse for the national agendas.

And still, the seed of common European politics has been sown. The lead candidates (Spitzenkandidaten) are already working, as if completely unaffected by the election results and the voters' motivation, for the establishment of a majority. At their first press conferences after the announcement of the exit polls, each of them announced the conditions for a compromise. The main claimant for future president of the Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, said he would not kneel before the Socialists and made it clear that he is ready for concessions with the Liberals and the Greens. Ska Keller, one of the Greens' candidates, said though that "not a single green vote" will go for a programme which is not at least a bit green. Martin Schulz did not seem happy with the outcome but said he was ready for talks. Guy Verhofstadt positioned himself as a key factor, but his group has problems that need to be resolved soon.

The rule for forming a group in the European Parliament is at least 25 MEPs from at least 7 member countries. Currently, this does not seem so. Mr Verhofstadt said his party was in negotiations with 6 countries on 15 seats. He did not sound as someone who had lost hope to become president of the Commission, given that a unity is reached on a compromise figure. The negotiations will be tough, but with huge stakes. If united, they will be able to establish a stable, two-third majority of 521 people out  of 751 MEPs. All the other groups and non-attached members are a force of 230 deputies. This means that the European Parliament will continue to function to a large extent as before.

of 751 MEPs. All the other groups and non-attached members are a force of 230 deputies. This means that the European Parliament will continue to function to a large extent as before.

However, what matters is what will the Council do. British Prime Minister David Cameron has already signalled he is not happy with the outcome and the possible election of Jean-Claude Juncker as head of the Commission because he does not fit into his plans for a reform of the EU to the British liking. British media have revealed that he had started even before the elections a diplomatic offensive to gain support for another candidate. Hungary's Prime Minister Victor Orban, whose party has again triumphed. also had said that he would not back Juncker. Orban was among the EPP leaders who bet on Juncker's rival in the inter-party race at the congress in Dublin - Michel Barnier.

The problem with the candidates' legitimacy is that it is not clear to what extent voters had voted for a certain party only to support them. The lack of a transnational list or a special preference to the national list dedicated only to the candidate for Commission chief prevents us from making more precise analyses. In any case, though, the common European campaign had an impact on the European public domain which confronts leaders with a very important choice - to continue business as usual or to give common European politics a chance. If they choose the former, this will secure short-term political stability for them. With the latter option, though, it is more than certain that the European politics will exert huge pressure on national politicians and will be a direct competition for them.

In the same time, it will give voters the chance to choose on their own whether they want more supranational politics or more of the same that is being offered to them. The analysis of the political moods in the member states is yet to answer many questions one of which is whether citizens lurch for populist and nationalistic options simply because nothing else is offered on the national scene? Another question is whether providing supranational options will invoke greater interest in European issues. Either way, it will mean that national politicians will no longer be monocratic "owners" of their voters.

The need of new political options is huge

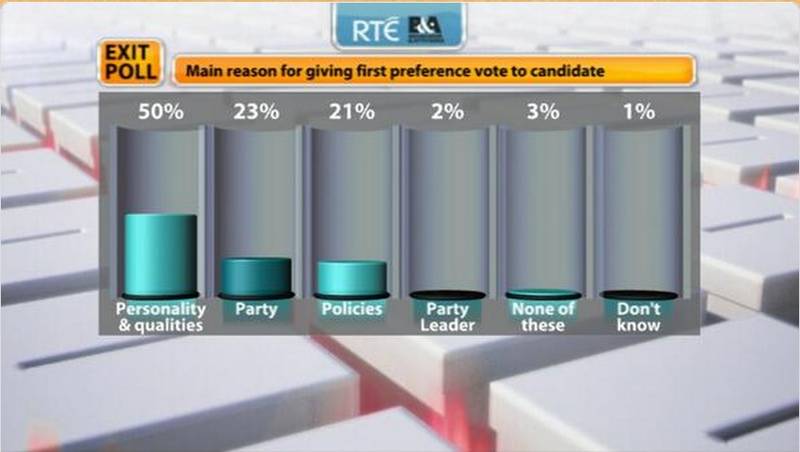

With the development of the European Union as a project, especially after the debt crisis in the euro area, as well as with the already complete process of globalisation, the traditional political ideologies have started to crumble down. In some countries, this process is slower and hesitant, but in others the political environment is very fertile. In many member states, practically, there are no big surprises, but in some there are political novelties that deserve attention. For instance, in Ireland, on the rise are independent candidates who have taken the biggest share of votes - totally 27% - while the mainstream Irish parties have shared 22% each and less. And this with some of the highest voter  turnouts - 51.2%. Another interesting moment in Ireland are the data from the exit polls of the Irish national TV.

turnouts - 51.2%. Another interesting moment in Ireland are the data from the exit polls of the Irish national TV.

Data show that 29% of the Irish voters were influenced in their decision whom to vote for by their country's exit from the Troika programme. 23 per cent of those polled were motivated to go out and vote because of the arrest of Sin Fein's leader Jerry Adams. The most interesting thing is, though, that the biggest number of respondents stated that they voted for person and idea not for a party. This explains the large number of independent candidates. These data clearly show that the political parities in Ireland are less and less adequate and citizens are seeking new possibilities. A trend which is likely to echo in other member states as well.

In Sweden, generally, the outcome remains the same, but what is new is that for the first time the country has sent a representative of the Feminist Initiative. This is a political party, established in 2005 as a heir of a civil initiative with the main aim to put an end to the patriarchal model. This is a very EU agenda given that one of the most popular European topics lately has been precisely gender equality and especially equal payment for women and men for the same kind of labour. The party will be part of the Liberal group.

In Latvia, undeniable victor is former premier Valdis Dombrovskis's party, but what is new is that for the first time a member of the European Parliament will have the Latvian Russian Union. This is a party that claims that all minorities (not only the Russian) in Latvia are not equally treated. This outcome should ot be ignored, especially against the backdrop of the tensions along the EU's eastern border.

Spain, which, too, had a sort of a bailout, projects itself as a country whose voters are thirsty for something new. The fourth political force at the EU elections, which will have five MEPs, is the young party Podemos (which means roughly "Yes, we can"), established in March. This is the party of protest in Spain against the high unemployment and the measures to master debt. Regretfully, each country filed various data in the common portal the European Parliament had for the elections, so it cannot be seen what precisely has motivated the citizens in the other member states as well. The decision of a  large part of the Greek voters to support left or far left parties with an inclination to fascism and anarchy seems logical.

large part of the Greek voters to support left or far left parties with an inclination to fascism and anarchy seems logical.

However, it is difficult to understand why in Hungary are winning parties which, without hiding, restrict democracy or parties who have their own military forces like Jobbik, for instance. It seems at this stage that the European Parliament will work as usual, but this will be the last parliament of the EU in the form it has now. From here onward there are two paths - either more union or less. The current situation will no longer endure the pressure. This is precisely why these elections were, indeed, different.

| © European Commission

| © European Commission | © euinside

| © euinside Angela Merkel | © Council of EU

Angela Merkel | © Council of EU