The Countries from the Enlargement Process Have Huge Problems with Media Environment

Adelina Marini, November 11, 2013

One of the things that immediately draws the attention in the European Commission progress reports for the countries from the enlargement process - those from the Western Balkans and Turkey - is that all of them reveal a very sick media environment. Unless that environment is reformed, media freed and they begin to report in an unbiased way, objectively and critically the developments in their countries we cannot expect the process of enlargement to get a new impetus and the countries will begin quickly to implement all the delayed reforms. Their progress will every year be visible and easily measurable. Otherwise, however, we will continue to read almost the same reports no matter how EU Enlargement Commissioner Stefan Fule or whoever will succeed him next year will change the approach.

Although some countries from the process have not yet started negotiations, others are just beginning to and a third group are in the very beginning, the similarities in the problems with (of) media are striking. What makes the situation even more serious, though, is that many of the things said in the reports Stefan Fule presented in mid-October, are completely valid for Bulgaria, for instance. It is no wonder in this sense that in Bulgaria the process of reforms has stalled a little after accession and even the especially fabricated to ensure they will continue Cooperation and Verification Mechanism has failed to keep the attention of the political elite in the country on the establishment of a democratic society, free market economy, independent judiciary, transparent public administration.

Although some countries from the process have not yet started negotiations, others are just beginning to and a third group are in the very beginning, the similarities in the problems with (of) media are striking. What makes the situation even more serious, though, is that many of the things said in the reports Stefan Fule presented in mid-October, are completely valid for Bulgaria, for instance. It is no wonder in this sense that in Bulgaria the process of reforms has stalled a little after accession and even the especially fabricated to ensure they will continue Cooperation and Verification Mechanism has failed to keep the attention of the political elite in the country on the establishment of a democratic society, free market economy, independent judiciary, transparent public administration.

Currently, the condition of the media environment is "measured" in the introductory part of the report and is reviewed much more in detail in Chapter 23 - Judiciary and Fundamental Rights. This year's report shows a desperate picture as the situation is severest in Macedonia, Montenegro and Turkey, although the top position can easily be contested by Bosnia and Herzegovina.

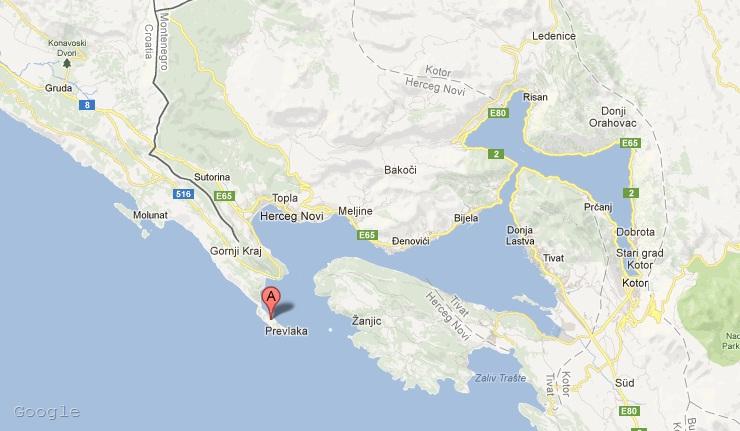

Montenegro

At the moment, the only country the European Commission is negotiating for accession with is Montenegro. This is also the first country with which Commissioner Fule is experimenting a new approach - the negotiations to begin from the toughest chapters, namely 23 and 24. It is still too early to judge what the effect of it is because the country has been negotiating for only a year. The dissection of the media environment, however, reveals particularly worrying problems. In the report, it is written down that in spite of the recently pronounced sentences and investigations of cases of violence against media, still many old and not as old cases of violence against journalists, including attacks on media property, have not been resolved. Podgorica is called upon to work more actively on investigating and prosecuting attacks against journalists. Thus formulated, the criticism shows that the country has scored a humble progress in that area.

Moreover, the Commission is concerned with the growing number of cases of attacks against journalists and media. It is also reported that the efforts for privatisation of state-owned print media had failed. According to the Commission, the state has violated the media law which bans it from establishing print media. Besides, a reason for concern is another practise which is quite common in Bulgaria - funding of print media through state advertisement, which is not realised according to the public procurement rules and could hamper competition on the media market.

"Some progress" is achieved in introducing a new model of self financing of media. However, the usage of the phrase "some progress" is not at all encouraging. The Commission sees another problem in the amendments of the law on electronic media, adopted in January this year, which require the Agency for Electronic Media to transfer any budget surpluses back to the treasury. Besides, the Parliament also obliged the Agency to revise its financial plan for 2013. This, according to the European  Commission, undermines the independence of that body. The assessment of its work in the report, in general, is weak, especially in terms of its capacity to oversee.

Commission, undermines the independence of that body. The assessment of its work in the report, in general, is weak, especially in terms of its capacity to oversee.

Another problem observed in Montenegro is that the efforts to apply professional and ethical standards "remain a challenge for most media". Beyond the Brussels's jargon, this means that to a large extent media in the tiny Balkan nation lack professional and ethical standards which undermines in the long-term the implementation of reforms in all sectors in the country.

Serbia

The great performer in the enlargement process this year is Serbia. This, however, does not mean there are many reasons to celebrate. After the leaders of the EU member states agreed to begin negotiations with Belgrade, currently a screening of the legislation is taking place and is expected the negotiations to begin in January. Naturally, again, first from chapters 23 and 24. And although the attitude to the most problematic country in the region so far is really largely-hearted, the Commission clearly warns that "Serbia will have to sustain the momentum of reforms over time in the key areas of the rule of law, particularly judicial reform and anti-corruption policy, independence of key institutions, media freedom, anti-discrimination policy, the protection of minorities and the business environment". This appeal shows quite clearly the scale of reforms Serbia needs.

As I mentioned in the beginning, though, for the realisation of this total socio-political and economic transformation free and critical media will be needed. And the situation in the country is not very encouraging. The first steps have been made, like, for instance, decriminalisation of defamation and establishing a special committee to "cast light" onto the cases of unresolved murders of journalists. Investigations had begun. After its experience with Bulgaria, where due to problems with media environment for a special meeting in Sofia arrived Commissioner Neelie Kroes last year and recommended the government to do what is necessary to ensure transparency of media ownership, the Commission already pays serious attention on this issue in the enlargement countries as well.

Still, transparency of media ownership is not addressed, as well as the financing of the sector, the report on Serbia says, but as if this is written particularly for Bulgaria. Reports are quoted of orchestrated media campaigns in certain tabloids against the opposition, coalition partners or independent bodies. In such media details are being revealed of ongoing investigations or upcoming arrests are announced on the basis of leaked information from police sources, the investigation or the prosecution, which is a cause of concern according to the humble and well measured language of the Brussels's bureaucracy. Translated to a normal language, however, this finding is a heavy verdict of the condition of the Serbian media environment.

The resolution of another grandiose problem has also not started yet - the direct state funding and control over media, including at local level. The funding of the two public media - RTS and RTV - puts into question their survival, especially against the backdrop of the RTV's role for the broadcast of programmes in minority languages, the document says. Another area that is a cause for concern for the Commission, is related to the procedure for appointment of members of the Republican Broadcast Agency, the equivalent of the Bulgarian Council for Electronic Media. As in Montenegro, in Serbia, too, the threats and violence against journalists remain "remain a significant factor in self-censorship". Another very serious problem in the Serbian media environment is the lack of final sentences for provoking racial, ethnic of religious hatred, as well as intolerance.

Turkey

The eternal candidate for EU membership has got a new eyewash with the hope that this will keep the country in the orbit of European values and area of influence. On November 5th the negotiations have been resumed on Chapter 22, which covers regional development and structural instruments. No one in the EU is currently able to say whether this is a resumption of negotiations and if other chapters will follow, but the member states accepted the arguments of Enlargement Commissioner Stefan Fule that it is better to negotiate with Turkey rather than keep the country isolated, especially after this year's protests in the Gezi park. Given the uncertainty will this be the last chapter for the next 3-4 years, the negotiations on it will hardly inject the desired new energy in the negotiations process, the lack of which can be seen with a bare eye in the Commission's report on Turkey for the past year.

In the area of media, the findings are more than worrying: "Problems remained, including continued pressure on the media by state officials, widespread self-censorship, the firing of critical journalists, frequent website bans and the fact that freedom of expression and media freedom are in practise hampered by the approach taken by the audio-visual regulator and the judiciary". According to the European Commission assessment, statements of state officials often are a reason for instigation of investigations by the prosecution. Moreover, state officials themselves launch investigations against critical journalists and writers. In the Commission criticism there is another problem which entirely describes the Bulgarian situation - high concentration of media ownership in the hands of "industrial conglomerates with interests going far beyond the free circulation of information".

It is also pointed out that mainstream media hardly reported on the protests in the Gezi park in the beginning of June. Columnists and journalists are often laid off or forced to leave after they criticised the government. "As a result, freedom of the media remained restricted in practise", is the European Commission's severe verdict. Brussels did not miss the fact that often high placed officials view social media as a threat to society. The report does not mention any concrete names, but things go as high as  Prime Minster Erdogan is, he himself the author of a remark in the same spirit, especially in terms of Twitter where his team maintains an account.

Prime Minster Erdogan is, he himself the author of a remark in the same spirit, especially in terms of Twitter where his team maintains an account.

Progress is noted only in terms of the Kurds as it is pointed out that there is an opening toward free debates on issues considered sensitive. Those are the Kurdish and Armenian issue. The public usage of Kurdish language has also partially been normalised. In spite of this ray of hope, though, the prosecution of tens of mainly left and Kurdish journalists has continued, especially under the strongly criticised by the EU Article 314 of the Turkish Penal Code for membership to an armed organisation.

Albania

The European Commission has recommended negotiations to begin with Albania which is hardly an occasion for celebration in Tirana. Simply, the Commission, out of desperation that it had already depleted all ways to demand reforms in some of the most underdeveloped countries in the enlargement process, is trying to provide a juicy carrot, thus hoping to unleash will or at least an impetus for reforms. Somewhat stimulating is that in the European Commission report media do not have too much attention. It is noted that there is progress with regard to the freedom of expression. It consists in the fact that in March a law on audiovisual media was adopted, which significantly improves the legal framework for electronic media in Albania. The law, however, does not provide for a procedure to appoint management bodies of the regulator and the public broadcaster to ensure their independence. In Albania, the decriminalisation of defamation has not been done yet and the interference of political and economic interests in media should be restricted, the Commission believes, thus wrapping up its findings.

Macedonia

This is the country which is more and more strongly being drawn into the black hole of timelessness and reformlessness. In the course of five years the Commission was recommending a start of accession negotiations with Skopje, but the lack of a solution of the name issue with Greece continues to be an obstacle for the start of the negotiations. Commissioner Fule believes that the more Macedonia remains in the twilight zone, the more it will go back. And how far it has gone back can very clearly be seen from the report on the country, especially in the part about media. Some media, especially the public broadcaster, did not provide a balanced reporting of the election campaign for the local elections in March and April this year. Besides, in spite of the legislative progress, media freedom continues to deteriorate in Macedonia as well as the reputation of media, is one key finding in the report.

Confidence between the government and media representatives is seriously harmed by the events from December 24th 2012 and the media dialogue, the purpose of which was to start a process of repair, has been suspended. "The media environment remains highly polarised", the Commission believes. Here, as in other countries in the region, a cause for concern is the government funding of certain media through advertisement. The Commission also saw indication of increased intolerance against homosexuals, like, for instance, through repeated physical attacks on the Centre for Support of Homosexuals in Skopje. Often can be observed homophobic media content. There are no adequate investigations of such cases.

"Hate speech during sports events, violence in public spaces and demonstrations increased tensions, exacerbated by often biased reporting by the media", is another very tough diagnosis of the Macedonian media environment by the Commission. The public media do not provide pluralistic and balanced reporting of news. Many media, especially on the Internet, do not respect the right of privacy. But in spite of these very worrying findings, Stefan Fule believes that Macedonia should be given a chance and that many of the problems can be solved in the process of negotiations. He underscored many times, though, that the special high level dialogue is not a replacement of the negotiations. Undoubtedly, given the fact that the dialogue does not provide the most important boost - at least a horizon for a European membership.

"Hate speech during sports events, violence in public spaces and demonstrations increased tensions, exacerbated by often biased reporting by the media", is another very tough diagnosis of the Macedonian media environment by the Commission. The public media do not provide pluralistic and balanced reporting of news. Many media, especially on the Internet, do not respect the right of privacy. But in spite of these very worrying findings, Stefan Fule believes that Macedonia should be given a chance and that many of the problems can be solved in the process of negotiations. He underscored many times, though, that the special high level dialogue is not a replacement of the negotiations. Undoubtedly, given the fact that the dialogue does not provide the most important boost - at least a horizon for a European membership.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Another country in the region where the situation is deteriorating is the Dayton invention Bosnia and Herzegovina. "Complex connections between political actors, business and the media are putting democratic institutions and procedures at risk and making the detection of corrupt practises more difficult". This sentence in the report of the Commission is completely sufficient to describe the situation in the country. It contains in itself all other problems that have fallen under the Commission's observation. "Political and financial pressure on the media has increased. A recent decision by the Communication Regulatory Agency (CRA) to limit advertising time of public broadcasters could endanger their financing. Intimidation and threats against journalists and editors and polarisation of the media along political and ethnic lines remain an issue of concern. The political, institutional and financial independence of the Communication Regulatory Agency remains to be secured".

Bosnia's future, however, continues to be put by the EU in direct consequence of the implementation of the ruling of the European Court on Human Rights regarding the Sejdic-Finci case. Only then can a conversation begin about a more enhanced process of approximation with the EU. When presenting the report on Bosnia Stefan Fule was trying to find the most appropriate words to describe not simply the lack of progress but the continuous sinking of the country. The only thing he could come up with was a comparison with the successes of the country's football team which managed to qualify for the world cup. He wished the political leaders to follow the team's example in terms of team work and common goal.

The Vienna-based think-tank European Stability Initiative, however, is of the opinion that the Sejdic-Finci case should not be an occasion to block Bosnia's European path. The think-tank offers three reasons in support of its claim. The first is that Bosnia, unlike the apartheid in South Africa, does not have a racist electoral system. The Bosnian system is even more liberal than that of South Tyrol's or Belgium's, where in certain cases it is required to publicly claim affiliations to a specific community. Something which is absent in Bosnia. The second reason is that Bosnia does not violate the main fundamental rights. The Sejdic-Finci case is related to the elections for the triple presidency in Bosnia, which is the hardest problem to solve and is not a violation of the rights enlisted in the European  Convention on Human Rights. It is a violation, though, of Protocol 12 of the Convention, which, however, is ratified by only 8 out of the 28 member states of the Union, the think-tank recalls.

Convention on Human Rights. It is a violation, though, of Protocol 12 of the Convention, which, however, is ratified by only 8 out of the 28 member states of the Union, the think-tank recalls.

And the third reason is that the implementation record of the European Court on Human Rights's rulings by Bosnia is much better than in many EU member states. This is precisely why the non-implementation of the ruling in that case cannot justify the blocking of Bosnia and Herzegovina's European path, is the conclusion of the analysts from the think-tank who underscore that the reforms the EU expects from Bosnia had not been demanded from other candidates, not to mention the member states. This is a strong argument, but irrelevant given the lessons from previous enlargements.

Kosovo

The youngest country in the Western Balkan region also got a prize for the successful process of normalisation of relations with Serbia - signing of an Association Agreement, which is the first step toward a fully fledged European membership. The situation of media in Kosovo, however is a cause of great concern. The Commission points out that in Kosovo there is no comprehensive law on media which leaves key areas of media completely unregulated. This includes issues like autonomy of journalists and editors, protection of professional standards in journalism, the right of response and correction of journalists, and also the right of refusal of journalists. As in other countries in the region, in Kosovo, too, threats against journalists and editors are a frequent practise. The same goes for political pressure and intimidation.

The independence of the Independent Media Commission has been hindered by the lack of resources and political interference in appointments of its members and the board of appeals. One member of the commission and two members of the board were appointed in spite of their ineligibility, the European Commission report says. Under question is also the long-term financial sustainability of the public media in Kosovo because the current model of financing is entirely based on the state budget which undermines its editorial independence.

Compared to the previous stages of enlargement, the Commission now pays much more attention on media environment in the candidate and aspiration countries. This is worth praising and should further evolve until a sustainable process of recovery is ensured. The problem is, though, what to do with the countries that already are members of the EU and where media environment is deteriorating. This is a huge challenge for the Commission and the EU at large, because unless an appropriate approach is selected this could undermine the efforts to cure the candidates and also to demand serious reforms in the neighbouring countries. According to Remzi Lani, executive director of the Albanian Media Institute, who was one of the panelists at the Sofia Platform this year (31.10-01.11), it is great that the Commission is taking media developments and freedom in the Balkans seriously because this is a lesson from the previous enlargements, like for instance in Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia, Hungary.

What we see now is that the situation with media in Sofia is no better than that in Tirana, is Mr Lani's opinion, the entire interview with whom you can watch in the video file above. His conclusion is that in terms of media freedom, the European integration has almost not worked at all. And if work is already ongoing on a mechanism to ensure the rule of law in the EU member states, probably the time has come to renew the conversation about the role of media, also in the EU.

Bakir Izetbegovic, Andrej Plenkovic | © Council of the EU

Bakir Izetbegovic, Andrej Plenkovic | © Council of the EU Aleksandar Vucic, Recep Tayyip Erdogan | © Serbian Presidency

Aleksandar Vucic, Recep Tayyip Erdogan | © Serbian Presidency Jean-Claude Juncker, Zoran Zaev | © European Commission

Jean-Claude Juncker, Zoran Zaev | © European Commission Donald Tusk, Boyko Borissov | © Council of the EU

Donald Tusk, Boyko Borissov | © Council of the EU | © Turkey Presidency

| © Turkey Presidency Elmar Brok | © European Parliament

Elmar Brok | © European Parliament Igor Luksic, Vesna Pusic | © Council of the EU

Igor Luksic, Vesna Pusic | © Council of the EU Stefan Fule | © Council of the EU

Stefan Fule | © Council of the EU | © Google

| © Google