Ashton's Successor Is Key to EU Security

Adelina Marini, July 28, 2014

On 30 August, the heads of state will gather for an extraordinary summit to decide who should take Catherine Ashton's post of EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Herman Van Rompuy's as president of the European Council. Such a decision was expected at the previous extraordinary summit on 16 July but it ended inconclusively. The two most discussed candidates in the EU are Italy's Foreign minister Federica Mogherini for Ashton's chair and Poland's Prime Minister Donald Tusk for Rompuy's chair. Against Mogherini a very strong front of eastern European countries was created who do not want at the EU foreign policy helm to be a person without experience from a country that maintains warm relations with Russia. And Tusk faced resistance, again, from UK Prime Minister David Cameron for purely domestic reasons. In spite of this failure, in the context of the circumstances surrounding the gunning down of Malaysian Flight MH17 the lack of a decision for these two EU top jobs is a good news.

On 30 August, the heads of state will gather for an extraordinary summit to decide who should take Catherine Ashton's post of EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Herman Van Rompuy's as president of the European Council. Such a decision was expected at the previous extraordinary summit on 16 July but it ended inconclusively. The two most discussed candidates in the EU are Italy's Foreign minister Federica Mogherini for Ashton's chair and Poland's Prime Minister Donald Tusk for Rompuy's chair. Against Mogherini a very strong front of eastern European countries was created who do not want at the EU foreign policy helm to be a person without experience from a country that maintains warm relations with Russia. And Tusk faced resistance, again, from UK Prime Minister David Cameron for purely domestic reasons. In spite of this failure, in the context of the circumstances surrounding the gunning down of Malaysian Flight MH17 the lack of a decision for these two EU top jobs is a good news.

Now the member states have an exceptional chance to repair the recent mistakes behind the logic of selection of people for top positions and most of all in the systemic undermining of the efforts to create a genuinely common foreign policy. The felling of the Malaysian air plane which caused that death of nearly 300 people from various nationalities, predominantly Dutch citizens, by pro-Russian terrorists who have occupied territories in Eastern Ukraine and supported financially and politically by Moscow, is the last drop that is supposed to overflow the glass of patience of the EU toward Putin's Russia. The policy toward Moscow should turn into a central one for the Union because there is almost nothing left that does not depend on relations with Russia - the situation in the Middle East, the countries from the Eastern Partnership, the EU's Arctic policy, the energy policy and even domestic policy in some member states. We should not forget also the countries from the Western Balkans some of which are brutally straddled between their strategic goal to join the EU and their relations with Russia, especially after Moscow made it clear that the Balkans are an area of influence the Kremlin has no intentions to give up on.

EU has to select a high representative for the coming five years. Think about how big a period this is from the point of view of the time that took many member states to realise what Putin is and that Russia not only has no intentions to approximate to the the Euro-Atlantic system of values but it even acts as its rival. More than a year ago analysts and influential media began talking about a repetition of the Cold war, although then such views were rather in the interrogative, but last week the TIME magazine came out with a front cover saying: "Cold War II: The West Is Losing Putin's Dangerous Game". And the Newsweek announced on its front cover that Putin is public enemy number one for the West.

If the EU selects a weak figure or is led in its choice by purely domestic European priorities like gender equality (indisputably very important but it cannot be decisive right now) or which political force should he or she come from (important to democracy but geopolitically completely irrelevant because the foreign policy priorities of the political families are not key to defining the European foreign policy), this would predetermine the events in the EU in general. The foreign policy priorities of the EU are defined in the European Commission chief's agenda, in the programme of the rotating presidency as well as in the strategic guidelines of the member states. From this perspective, the party affiliations cannot be leading.

A major criterion for selection of the most appropriate high representative should be the lack of conflict of interest with the country he or she comes from. In this regard, a candidate from a state which is deeply dependent on Russia is a potential Trojan horse in the European foreign policy. If he or she comes from a country with deeply rooted economic and business relations with Russia that puts the candidate in a conflict of interest. This seriously narrows the circle of nations that can offer candidates but it is very important the EU to spend as much time as necessary to select the really best possible person. There will hardly be a second chance because no more evidence is needed that the Kremlin is skillfully taking advantage of the lack of a strong and single foreign policy centre and not the lack of a single voice but the lack of a common interest in terms of strategically important for the EU regions and states.

Russia is no longer a strategic partner but a threat to security. This requires a very different approach. The selection of a proper high representative will be a very strong signal to Putin that he will no longer dictate the rules. The new high representative should have a very clear mandate to make a comprehensive analysis of the economic dependencies of the member states and to present a clear plan how to overcome them. Such a mandate cannot be found in the strategic agenda outlined by the leaders in end-June. The member states should empower the high representative to make decisions on his own on specific dossiers which means the capitals to clearly draw the red lines they will never allow to be crossed, as Barack Obama did, even facing the risk of an economic war with Russia. Apart from that, the multi direction talking on such a sensitive issue as Russia should be ended.

For one voice but following many agendas

The short and long-term future of the EU from a foreign policy perspective is defined by three main agendas. The first and very important is the strategic agenda of the member states, approved in the end of June by the heads of state or government. However, Russia is not mentioned at all neither as a name nor as a strategic subject of the common European foreign policy. It is only mentioned that the recent developments (without naming them) "show how fast-shifting the strategic and geopolitical environment has become, not least at the Union's eastern and southern borders". The leaders, however, do not demonstrate any conscience what stems from this because they say: "At the same time it has never been as important to engage our partners on issues of mutual or global interest". This does not make it clear whether the EU views Russia as a partner or as a subject of partners' actions.

The short and long-term future of the EU from a foreign policy perspective is defined by three main agendas. The first and very important is the strategic agenda of the member states, approved in the end of June by the heads of state or government. However, Russia is not mentioned at all neither as a name nor as a strategic subject of the common European foreign policy. It is only mentioned that the recent developments (without naming them) "show how fast-shifting the strategic and geopolitical environment has become, not least at the Union's eastern and southern borders". The leaders, however, do not demonstrate any conscience what stems from this because they say: "At the same time it has never been as important to engage our partners on issues of mutual or global interest". This does not make it clear whether the EU views Russia as a partner or as a subject of partners' actions.

The second agenda is Jean-Claude Juncker's vision, the new European Commission chief, which is based on the leaders' strategic guidelines. However, it is much more specific. The agenda is not final and depends on the members of the College. Before the European Parliament, however, Mr Juncker said that "The Ukraine crisis and the worrying situation in the Middle East show how important it is that Europe is united externally". According to him, it would be a bad choice to continue with the recent policy. Better mechanisms are needed to anticipate at an early stage the developments and to quickly identify common responses. From this perspective, the next high representative should be a strong and experienced player who should combine national and European instruments "in a more effective way than in the past". He or she should work together with the commissioners for trade, development and humanitarian aid as well as with the commissioner who will be responsible for the neighbourhood policy.

The third agenda is of the rotating presidency of the Council which as of July 1st has been taken over by Italy. In the Presidency's agenda Russia is mentioned but long after everything else and is definitely not a major priority. In the foreign affairs chapter, which spreads over six pages, there is only one paragraph on Russia which defines this country as a strategic partner. "Russia remains a strategic partner to address regional and global challenges. Therefore, Italy will encourage the EU to explore ways to revamp the dialogue between the European Union and Russia, and seize opportunities to enhance the strategic partnership, if the general context of reference could allow it".

Until several years ago it was a tradition the rotating presidencies to focus on national interests than purely European, but this was recognised as rather a flaw than a symbol of the "unity in diversity" during the drafting of the Lisbon Treaty. It introduced the so called troika presidency and significantly weakened the power of rotating presidencies. In this regard, the Italian foreign policy agenda is more than ambitious and is obviously in a conflict with the vision of the Commission and the European Council  as long as one can draw any clear conclusions from the latter. It is precisely such variety of agendas and different talking that is skilfully used by Putin.

as long as one can draw any clear conclusions from the latter. It is precisely such variety of agendas and different talking that is skilfully used by Putin.

It will hardly be an exaggeration to say that the EU is facing a historic decision. As this website wrote before, the key decision about deepening the integration within the euro area from June 2012 was taken under pressure by the crisis. Now there is a crisis in the Union's foreign policy structure and the moment is ripe for decisive actions. The selection of the next high representative will be the first step that will show to what extent the EU is capable of being a community. Because a strong economic and monetary integration is impossible without an adequate community foreign policy as becomes clear from the revealed energy dependences of many EU member states.

And here an important role to play has the European Parliament. If it proves incapable to overcome its trump card (gender equality and party distribution) it uses to exert its power in the EU, this will be a strong signal that it is not ready for such power. The MEPs should be aware what they will be judged for by the next generations - because they did not secure good gender balance in the Commission or because they contributed to undermining Europeans security.

Boyko Borissov, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU

Boyko Borissov, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU Boris Johnson | © Council of the EU

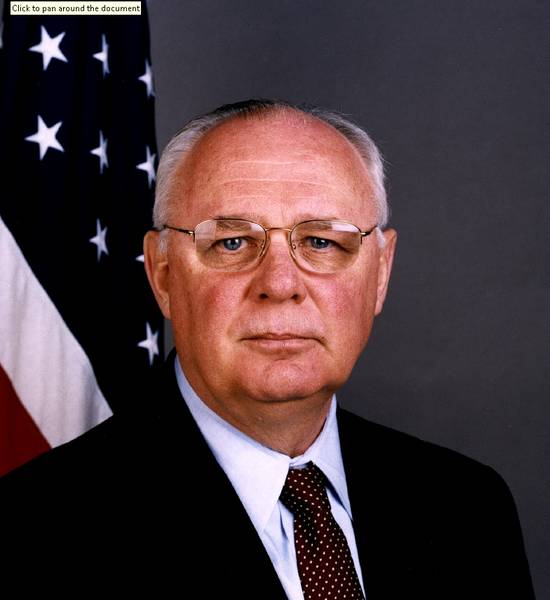

Boris Johnson | © Council of the EU James W. Pardew | ©

James W. Pardew | ©  Federica Mogherini | © Council of the EU

Federica Mogherini | © Council of the EU | © Council of the EU

| © Council of the EU Luis De Guindos | © Council of the EU

Luis De Guindos | © Council of the EU