Slovenia's Problem

Adelina Marini, August 7, 2013

Did you know that the Republic of Slovenia owns directly or indirectly shares in at least 80 companies the book value of which, according to 2011 data, is 8.8 billion euros or a little over 24% of the country's gross domestic product? Injecting public money for direct recapitalisation or payment of guarantees covers 1.4 percentage points of the country's budget deficit for 2011 which was 6.4 per cent of GDP. And that is precisely what is in the foundation of the crisis Slovenia finds itself at the moment. The country was shaken by a severe political crisis provoked by the complete lack of reforms, perspectives and a fully crashed confidence in the political class's capabilities to take the once Balkan and Central European miracle out of the trap of the past.

Did you know that the Republic of Slovenia owns directly or indirectly shares in at least 80 companies the book value of which, according to 2011 data, is 8.8 billion euros or a little over 24% of the country's gross domestic product? Injecting public money for direct recapitalisation or payment of guarantees covers 1.4 percentage points of the country's budget deficit for 2011 which was 6.4 per cent of GDP. And that is precisely what is in the foundation of the crisis Slovenia finds itself at the moment. The country was shaken by a severe political crisis provoked by the complete lack of reforms, perspectives and a fully crashed confidence in the political class's capabilities to take the once Balkan and Central European miracle out of the trap of the past.

Alenka Bratusek's government is trying to restore stability and implement reforms that were postponed for decades. On top of the reforms list is precisely privatisation of state-owned companies. According to an analysis of the European Commission, made by Svetoslava Georgieva, an economist in GD ECFIN in the European Commission, and David Marco Riquelme, a statistical assistant in the same GD, the state-owned firms in Slovenia generate one sixth of the Slovene economy and employ one in every eight people in the corporate sector. The data which the analysts used are from 2011 because by May 1st, when the analysis began, the 2012 data had not been complete yet.

Their analysis shows that part of the current situation could be tracked back to the choice of a privatisation model during the transition, i.e. back to the beginning of the 1990s when Slovenia, first of the countries in former Yugoslavia, gained independence. The privatisation model is called both in Slovenia and in analyses not only of the European Commission "gradual", meaning in stages, but this can be perceived, especially in Slovenia's case, as an euphemism of slow and sluggish. In the first stage of privatisation there were two options - privatisation through direct payment or through vouchers. Every citizen got privatisation vouchers which they could exchange for company shares or for shares in authorised investment funds.

The problem is, though, that back then there was a dominant preference for internal control which can be explained, the analysts from the economic directorate of the Commission write, with the then existing business culture that left ownership in the hands of fragmented but collectively powerful internal people or of state dominance. As a result, there were not many incentives to increase profitability or to restructure companies. That first stage of the Slovene privatisation practically created one of the main  problems of the today's Slovene economy - the interconnectedness and complication among firms, state, banks. A knot the untwining of which is the most difficult task for the government of Ms Bratusek.

problems of the today's Slovene economy - the interconnectedness and complication among firms, state, banks. A knot the untwining of which is the most difficult task for the government of Ms Bratusek.

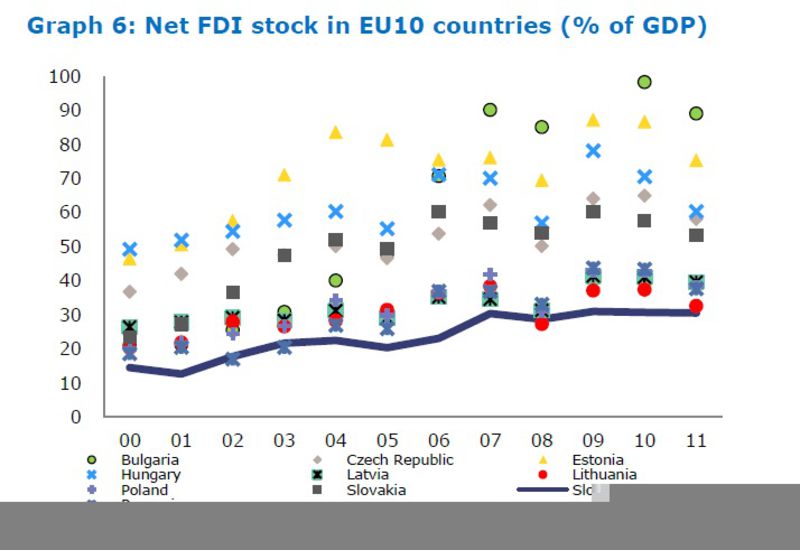

The second stage of privatisation in Slovenia aimed to consolidate ownership and increase the share of strategic investors. Due to the already established domination of internal owners and the state, however, there was a focus on management buy-outs with the support of huge loans from state-owned banks. This is also the main reason why Slovenia was throughout the entire transition period toward market economy the country with the least foreign direct investments of all the countries in Central and Eastern Europe as, according to Svetoslava Georgieva's and David Marco Riquelme's table, Bulgaria is first in terms of attracting FDI in the period 2007-2011, followed closely by Hungary.

The very high level of state ownership is an impediment for the development of effective corporate culture as well which, for its part, leads to low profitability and financial vulnerability during the crisis. As a matter of fact, it is worth noting that the problem with the excessively big role of the state in the Slovene economy was highlighted a number of times in the pre-accession reports of the European Commission for Slovenia, but also in the convergence reports preceding the accession of the small Alp state in the euro area - the first from the big bang enlargement of the EU toward Central and Eastern Europe.

In their report on Slovenia's progress toward European membership from 2003 (Slovenia joined with the big wave in 2004), the Commission points out: "Slovenia is a functioning market economy. The continuation of its current reform path should enable Slovenia to cope with competitive pressure and market forces in the Union". Up to the crisis in Europe in 2009, this was correct. And in 2006, the year before Ljubljana's accession in the eurozone, the Commission wrote in its convergence report that the Slovene economy was highly open for trade, "but it is relatively little receptive to foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows. Slovenia has also adopted a relatively gradual approach to structural reforms particularly with respect to liberalisation and privatisation", is said in the European Commission report from 2006 which practically gives green light for the country's accession in the single currency zone.

It is interesting to note that in this report it is pointed out that the weak FDI flow is a direct result of the privatisation process. It also says that the low intensity of FDI "may limit competitive pressures in the  domestic market".

domestic market".

In an attempt to avoid asking a bailout loan that could lead to the implementation of a severe programme of relentless reforms, the government in Ljubljana decided to choose a path of its own announcing a programme that includes the privatisation of 15 state-owned companies. The overall debt, according to the European Commission analysis, of all state-owned companies in Slovenia amounts to at least 30 per cent of the gross domestic product. Among the strategic companies with a contribution to the common debt are the infrastructure company DARS which "holds" 8.1% of the debt, the popular in the region supermarket chain Mercator with 3.3% and the petrol company Petrol (1.7%). Exactly the difficult situation with the state-owned companies has led to the "deal of the century", as it was described in Croatia, awaited many many years and which a series of Slovene governments objected for a long time.

This is the deal for the purchase of Mercator by the Croatian company Agrokor, owner of the biggest supermarket chain in Croatia Konzum. Last year Mercator filed a loss of 62 million euros. The agreement for the sale of Mercator was signed on June 14th this year, allowing Agrokor, whose owner is the richest man in Croatia, to buy 53 per cent of the Slovene company. The overall value of the deal is 452 million euros which will be financed mainly by recapitalisation of Agrokor by financial institutions like the EBRD and other financial companies. The deal has a huge significance for the region because it makes the Mercator-Konzum group the biggest in Central and Eastern Europe. According to analysts, the overall trade will amount to 6.8 billion euros.

Slovenia's impact on the survival of the euro is not as huge as that of Greece, for instance, but it is another lesson about the failures in the construction of the Economic and Monetary Union of the EU. The fact that in a series of reports before Slovenia's membership in the EU and later in the euro area privatisation was pointed as a problem but no measures were undertaken, means that either the systemic significance of the problem was underestimated or that the motives to accept Slovenia economically unprepared were entirely political.

Slovenia's impact on the survival of the euro is not as huge as that of Greece, for instance, but it is another lesson about the failures in the construction of the Economic and Monetary Union of the EU. The fact that in a series of reports before Slovenia's membership in the EU and later in the euro area privatisation was pointed as a problem but no measures were undertaken, means that either the systemic significance of the problem was underestimated or that the motives to accept Slovenia economically unprepared were entirely political.

Either way, the result is visible - another fissure in the eurozone's foundations. And if it is good that Slovenia is a tiny country and hardly its crash would have systemic impact, the national governance of an economy with an impact on the common European system raises even more the issue about the need of an overall change of the euro area's architecture, especially in the part that concerns making decisions, if possible preventive ones.

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU