Which Is The 3rd Largest Euro Area Economy? Berlusconia

Adelina Marini, October 11, 2013

In the United States the Tea Party holds the government hostage, while in Italy until last week Enrico Letta's cabinet was (is?) held hostage by Silvio Berlusconi - probably the biggest political ego in Europe since the end of World War II. And if the US's political and financial instability threatens the entire global economy, Il Cavaliere's homeland has a huge importance for the survival of the eurozone ... again. Let us remember, after all, that for the first time in EU's history was allowed a gross, although masked in a sufficiently complex diplomatic language, interference in national sovereignty by appointing in Italy a technocratic government from the outside. After the great danger Italy to default right after Greece, Portugal and Ireland, thus putting an end to the biggest pride of European integration - the single currency - EU united its efforts and put pressure on then Prime Minster Berlusconi to step down.

In the United States the Tea Party holds the government hostage, while in Italy until last week Enrico Letta's cabinet was (is?) held hostage by Silvio Berlusconi - probably the biggest political ego in Europe since the end of World War II. And if the US's political and financial instability threatens the entire global economy, Il Cavaliere's homeland has a huge importance for the survival of the eurozone ... again. Let us remember, after all, that for the first time in EU's history was allowed a gross, although masked in a sufficiently complex diplomatic language, interference in national sovereignty by appointing in Italy a technocratic government from the outside. After the great danger Italy to default right after Greece, Portugal and Ireland, thus putting an end to the biggest pride of European integration - the single currency - EU united its efforts and put pressure on then Prime Minster Berlusconi to step down.

In his chair was installed former EU commissioner and author of ideas for the development of the European single market Mario Monti, tasked with the mission to bring Italy back to the Italians and the Europeans. The magic worked, although for only two years, to remind the Italians what normality was and to the Europeans - how nice it was without the Berlusconi eccentricities.

Berlusconicentric politics

Alas, normality in Italian politics was ended in the beginning of the year when Berlusconi, again, decided he no longer could stand outside the game and demanded from his party (People of Freedom, PdL) to withdraw their support for Monti's government. In this way, he found as Monti himself and his fellow technocrats in the cabinet so the EU and the euro area in particular completely unprepared. The parliamentary elections in end-February produced an even more complex picture - no one won and everyone won simultaneously, especially the party of the comic Beppe Grillo. Because of the deadlock, the forming of a government took months of tough negotiations, loss of achievements in the two years of normality and deteriorating perspectives.

The situation literally repeated itself this autumn, less than a year after the formation of Enrico Letta's fragile government, because Berlusconi took offence by the court who manifested great mercy to him and sentenced him to four years in prison for tax fraud, but due to his age the court demonstrated compassion and announced he could serve only a year in prison and the rest by public judgement. The price of the judicial mercy, however, was the parliament to decide whether to suspend his term as a senator so that he could serve his sentence. Precisely the anticipation the Senate committee to announce their decision whether Berlusconi should stay in the Senate or not provoked Il Cavaliere to play va banque and try to measure his public temperature. It showed that he is not as hot a politician as he used to be as, because of the danger of an even greater political crisis than that from the first half of the year many of his own deputies openly said basta and signalled they would not support the action of overthrowing the cabinet.

This forced the quite vital for political life, but too weak to serve a sentence Berlusconi to put the weapon down and give up a march against ... himself. For now the big storm is over but neither Italy not the EU are safe from Berlusconi. His oust from parliament for sure will inflict a severe strike on him, but this definitely does not mean an end to his political career, commented the British eurosceptic think-tank Open Europe who follow the situation in the country closely. The main reason is that the huge public support he enjoys will not vaporise overnight. In the eyes of many Italians Il Cavaliere remains an example of a successful self-made entrepreneur and a victim of conspiracy of left-leaning judges. Does this sound familiar? Somewhat southern?

The big question, however, is why was Berlusconi left in the first place to risk the future of his country for the sake of his own survival. This question poses Gianni Riotta on the pages of the influential American foreign policy magazine Foreign Affairs. Under any criteria (of normality we should add) Berlusconi's political career should have long been over. But today, one in every four Italians state that they would vote for him.

From a media magnate to a tax saviour

One of the reasons, according to Gianni Riotta, for the Italian national love is the fact that Berlusconi owns prodigious media empire (also familiar, right?). He controls three TV networks, a number of radio stations, daily newspapers, magazines and publishing houses. Of course, we should not forget the football club Milan as well as the broadcasting rights for the team's matches. But to reduce everything to media influence would be too simplistic, believes the columnist in La Stampa and professor in Princeton. The real answer, he writes, can be summed up in one single word: taxes. Berlusconi's main  base believe that Italy's entire political and legal system is turned against them, especially the tax code. Il Cavaliere has always succeeded to feed this scepticism and literally hostility.

base believe that Italy's entire political and legal system is turned against them, especially the tax code. Il Cavaliere has always succeeded to feed this scepticism and literally hostility.

The Italians do not like Berlusconi because of his alleged ties to the Mafia or his strongly racist statements or his skirt-chasing. They like him because of his charming populism. The Italians are famous with one of the highest tax burdens in Europe and may be the most complex tax system. Not that Berlusconi solves these problems, but at least he does not raise the taxes. While the Socialists promised that they would raise them to fill in the coffers. In this sense is one of the recommendations of the IMF to Italy from the end of September - to move toward reducing the costs and taxes on labour and capital because they are among the highest in the eurozone.

Enough charm, you need competitiveness

Italy is the third largest economy in the euro area and that is why the developments in the country no longer are Italy's own business. This is one of the main reasons why the European Commission sent its heavy artillery in Rome on September 17th to speak not in a university room or a hotel, but in parliament. The European Commission Vice President responsible for the economic and financial affairs of the EU and the euro area Olli Rehn told Italians MPs that because of the severe economic situation the Union has COLLECTIVELY asked Italy to undertake urgent actions. In July, the Council confirmed the European Commission recommendations to Italy among which were reducing public debt; implementing reforms on the labour market and products; improving the functioning of the administration and the judiciary (again familiar). Italy is one of the countries with the biggest tax burdens on labour in the EU, Olli Rehn then said.

He started his speech with his ordinary allusions to sports, saying that a famous countryman of his (Kimi Räikkönen) was a very discussed figure in Italian media in September because of the negotiations with Ferrari. "But let’s be clear: talent alone will not be sufficient. Ferrari, like Italy, has always stood for tradition, style and quality craftsmanship. But in order to win on the global growth racetrack you need to design the most competitive engine and stay ready to change and adapt", was the message of the  European Commission Vice President. Moreover, he directly told the MPs that the political uncertainty in the country was holding back the so much needed investments and impeded recovery.

European Commission Vice President. Moreover, he directly told the MPs that the political uncertainty in the country was holding back the so much needed investments and impeded recovery.

Every word in Olli Rehn's speech was carefully measured and clearly aimed, like the key sentence: "A deep fiscal union can be only created through a profoundly democratic process, at both national and European levels. Any step towards increased solidarity and mutualisation of economic risk must be combined with increased responsibility and fiscal rigour – that is, with further sharing of sovereignty and integration of decision-making". With this sentence Olli Rehn, practically, explained quite clearly the German position of gradual and slow construction of the banking union, precisely because of the instable political cases like the Berlusconi case in Italy.

Of course, democracy in itself is not a precondition for this. Through democratic processes can rise strong leaders with a vision, who can bring a country forward, but political egoists can also rise who, through populism, can serve only themselves leaving their countries adrift. The problem with the EU, though, is that voters, for instance in Italy, elect Berlusconi whose behaviour harms other nations.

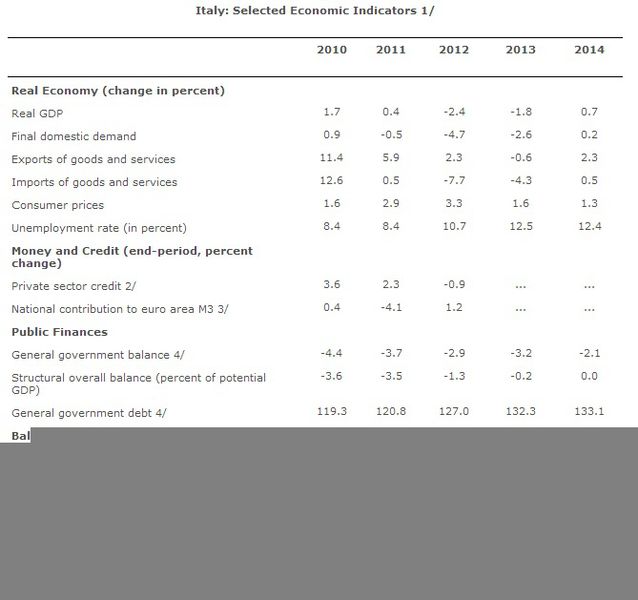

And that harm, presented in numbers, speaks for itself. The Italian economy is in a recession for almost two years now, according to IMF data. The gross domestic product shrank in 2012 by 2.4%, as negative growth is expected this year, too. The Fund sees a good perspective for a positive growth next year, but that depends on too many factors, the main of which is political stability and also the environment in the euro area and the global economy at large. And this closes the circle because if the Italian economy is fragile this would shake the euro area, which will return as a boomerang onto the Italian economy where many serious underwater rocks lie.

The biggest of them is the situation with Italian banks. The ratio of nonperforming loans has almost tripled since 2007. This is the main reason why the credit conditions in the country are very tight, the interest rates are high, which further depresses the private sector spending. IMF takes as a foundation for their forecast the lack of additional structural reforms which, it all seems, is the most probable scenario because, although Letta's government survived, it still is a hostage of Berlusconi's party which seems allergic to any reforms. Not only this, but Beppe Grillo's party, which is against everything and  everyone, still is a major factor in Italian politics. If the situation remains unchanged, the mid-term growth perspectives would remain low, is the Fund's forecast from the end of September.

everyone, still is a major factor in Italian politics. If the situation remains unchanged, the mid-term growth perspectives would remain low, is the Fund's forecast from the end of September.

The origin of this forecast is exactly where the structural reforms are most needed - frozen productivity, difficult business environment, over-indebted public sector. Last but not least is the inefficient judiciary, which has an impact on the high costs for doing business, low foreign direct investments and the small size of companies and capital markets. In case there is a significant concussion, the banking sector might not hold up the pressure, is the IMF's opinion.

On October 15th, all euro area member states have to deliver their draft budgets for next year to the Commission and the Eurogroup. This will be the first exercise with the brand new legislation, the two-pack which was hard to adopt. A package of two legislative proposals for deepening of the economic coordination in the euro area. In November, the Commission will publish its opinions on all the 17 drafts. If one is not in line with the commitments the Commission will demand corrections. Olli Rehn expressed confidence in Rome on September 17th that Italy's government and the members of the Italian parliament are completely aware of the consequences from these rules, which Italy took part in writing and supported in the Council. This remark of Olli Rehn's shows quite clearly the Commission's fears of a failure of the implementation of the two-pack and another round of the crisis.

Because, as he explained, statements of the type "the crisis is over" (of French President Francois Hollande) are premature. "We all know that this crisis is no ordinary cyclical downturn. Its origins lie in the large and unsustainable macroeconomic imbalances that were allowed to accumulate over many years. In the case of Italy, the imbalances take the form of very high debt levels and a long decline in competitiveness. In particular, the price competitiveness of the Italian economy suffered massively and unit labour costs have increased more rapidly than in the rest of the euro area since 1998".

It seems that the Italian MPs heard some of Olli Rehn's messages since they decided to keep the government. But this still does not mean political stability or even less structural reforms. And they know it. The question is do the Italian voters know that too.

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU

Klaus Regling | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU

Mario Centeno | © Council of the EU