Europe is Awakening for Russia … with a Heavy Hangover

Dragomir Ivanov, December 12, 2011

On the 8th of November 2011 the coastal resort of Lubmin, in Northeastern Germany, saw half a dozen political leaders gathering to turn on a tap and give the kick-off of the controversial gas pipeline Nord Stream. The pipe, named by former Polish president Alexander Kwasniewsky “a mine at the fundament of EU solidarity”, is already a fact.

On the 8th of November 2011 the coastal resort of Lubmin, in Northeastern Germany, saw half a dozen political leaders gathering to turn on a tap and give the kick-off of the controversial gas pipeline Nord Stream. The pipe, named by former Polish president Alexander Kwasniewsky “a mine at the fundament of EU solidarity”, is already a fact.

The same day Berlin and Warsaw sent a letter to Catherine Ashton, the EU High Representative for foreign affairs, calling on for re-consideration of the relations with Russia. In the letter, foreign ministers Guido Westerwelle and Radoslav Sikorski insisted that Brussels should demand from Moscow fulfil its commitments regarding the rule of law, human rights, media freedom and democratic values. The ministers pointed out that the announced “swapping of posts between President Medvedev and Prime Minister Putin is not encouraging”, but the EU must stay on the course to intensify its relationship with Russia and to overcome “the political and economic lethargy”.

Sobering-down from an illusory Realpolitik

The message signifies the emerging of a new tandem in the EU and also the timid awakening of Europe concerning the relations with Russia. The Duma elections, accompanied by manipulations and brutal reaction to the swelling protests, are speeding up the sobering in EU capitals.

The current EU policy toward Russia is based on the presumption that the Russian elites are willing and capable to conduct an overall modernisation. These hopes date back to the first mandate of Mr Putin (2000–2004) and the then imposed apparent stability following the chaos during the 1990s.

The wrongly understood “pragmatic realism” of former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder provided for mutually beneficial business relations in return to refusal from the “values’ approach”. Essential part of the deal at that time was energy and this is the reason why energy dialogue continues to dominate in all domains of co-operation between Europe and Russia. Angela Merkel continued Schröder’s line. “This is how the leading power in Europe legitimated the autocracy in Russia and created a life-supporting environment for it”, explains Lilia Shevtsova from Carnegie Moscow Centre.

But the global crisis has turned into a nightmare for Russia’s two-headed eagle. No one is deceived anymore that the ostensible democracy of Putin-Medvedev can go beyond the empty rhetoric. Of course, Russia still gains from the high prices of the energy resources but the much-awaited modernisation remains beyond the horizon. There is no rule of law, corruption is ubiquitous, bureaucracy is choking everything and the power is strongly personalised and entangled with the big enterprises. The feeling of most Russians is of a stalemate - a new “Brezhnevisation”.

Putin 3.0 – dreams for hegemony and bilateral agreements

Moscow compensates the internal stalemate with foreign activity. It seems that Putin 3.0 intends to confront the West in at least two dimensions: the anti-missile defence with the US and the post-Soviet space with the EU.

Russia understands that it can no more pester China for a military-political alliance to counterbalance US unipolarity. “China is no more an emerging market but an emerging superpower that increasingly sees Russia as a junior partner. […] Many in China have come to share EU’s frustration with the poor Russian business climate and rampant corruption”, states in a recent study the European Council for Foreign Relations (ECFR).

Meanwhile, for internal use only, Putin continues to dream about hegemony. In October he presented in the newspaper Izvestia his idea about a Eurasian union – not as a resurrection of USSR but rather as a “supranational union of sovereign states” - a kind of integration project. In November Russian MPs and political analysts even suggested Bulgaria to join this new organisation.

At the same time, Kremlin attacks with bilateral agreements the peripheral countries that come into the scope of EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood policy. The pressure on Ukraine to join the customs union between Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan is extremely strong. Moldova is also subject of pressure because of the Transnistrian conflict.

The open enforcing of Russian influence goes through three channels – military bases, pipes and bits of national economies. Three military examples: Moscow’s Black Sea navy will stay for another 25 years in Ukraine, Russia will use its army base in Armenia until 2044 and there are 7–9,000 Russian troops in the Georgian rebel republics Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Those bilateral agreements undermine the European policies, too. The ambitious EU project “Partnership for Modernisation” is practically blocked by Moscow's agreements with 18 from its 27 Member States. “Russia, which has always worked with Europe on two levels—in Brussels and in the member capitals—will 'woo' the latter all the more forcefully, which further supports the 'nationalisation' of European politics, commented last year Dmitri Trenin, analyst with the Carnegie Moscow Centre.

Strategies for a “post BRIC” Russia

The Old Continent is buried under economic problems and does not desire any foreign policy trouble. The emerging “Europe on two speeds” provides to a certain degree for less commitment in foreign affairs. But the EU cannot afford not to have a policy for Russia.

The think-tanks are wondering what should the approach be to the “post BRIC” Russia – a country that does not stand anymore a level with Brazil, India and China. According to ECFR the strategy should focus on consolidation of the Union and deepening of the co-operation with Russia. But at the same time it has to prevent Russian bureaucrats from violating human rights and limit Putin’s ambitions to dictate in the post-Soviet space.

No matter how reluctant the empowered people in Moscow are to admit Russia and the EU are sharing the same boat in the stormy waters of the crisis. Europe is the biggest buyer of Russian energy resources and remains Russia’s most important investor and trade partner. Already at the start of the crisis in 2008–2009 the Russian leaders realised how dependant their country is on the European and global economy in terms of export and loans.

“Putin’s legitimacy loss will lead to escalating conflicts between Russia and the  West”, predicted in an unusually acute analysis the German Council on Foreign Relations that until recently spoke softly about Moscow. Stefan Meister, analyst, states that it is high time for the EU to see Putin’s system as it really is – authoritarian, anti-democratic and unwilling to reform. And to look for partners not so much among the Russian elite but among the citizens and the civil society in Russia.

West”, predicted in an unusually acute analysis the German Council on Foreign Relations that until recently spoke softly about Moscow. Stefan Meister, analyst, states that it is high time for the EU to see Putin’s system as it really is – authoritarian, anti-democratic and unwilling to reform. And to look for partners not so much among the Russian elite but among the citizens and the civil society in Russia.

Boyko Borissov, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU

Boyko Borissov, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU Boris Johnson | © Council of the EU

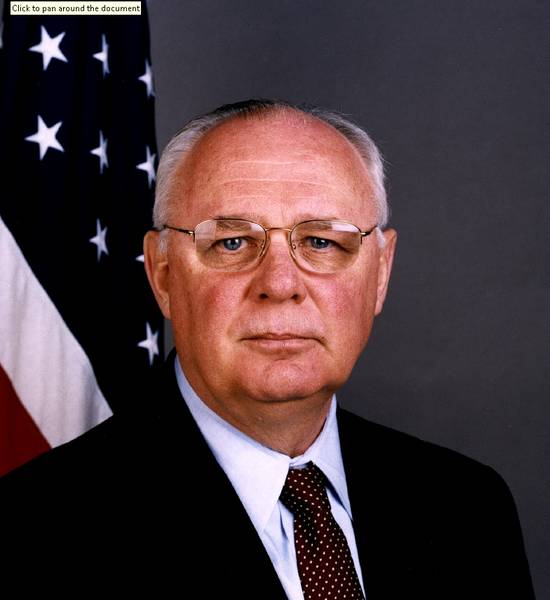

Boris Johnson | © Council of the EU James W. Pardew | ©

James W. Pardew | ©