EC Transfers the Fight Against Corruption to the Victims Themselves

Adelina Marini, February 13, 2017

In a landmark moment like today when illiberalism is leading a fierce battle against the rule of law and democracy in emblematic states, the European Commission is making a serious retreat from one of the most important things, which ensure the rule of law and sound democracy - fighting corruption. In a letter to the chairman of the European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) Claude Moraes (Socialists and Democrats, Great Britain) the European Commission First Vice-President Frans Timmermans (The Netherlands, Socialists and Democrats), whose portfolio includes namely the rule of law, explains why the EC will no longer make reports on the corruption situation in all the 28 member states. It was EUobserver that reported about this letter. So far the EC has issued just a single report in 2014, which was part of the efforts of the previous Commission of José Manuel Barroso (Portugal, EPP) to deal with the economic crisis in the EU.

In a landmark moment like today when illiberalism is leading a fierce battle against the rule of law and democracy in emblematic states, the European Commission is making a serious retreat from one of the most important things, which ensure the rule of law and sound democracy - fighting corruption. In a letter to the chairman of the European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) Claude Moraes (Socialists and Democrats, Great Britain) the European Commission First Vice-President Frans Timmermans (The Netherlands, Socialists and Democrats), whose portfolio includes namely the rule of law, explains why the EC will no longer make reports on the corruption situation in all the 28 member states. It was EUobserver that reported about this letter. So far the EC has issued just a single report in 2014, which was part of the efforts of the previous Commission of José Manuel Barroso (Portugal, EPP) to deal with the economic crisis in the EU.

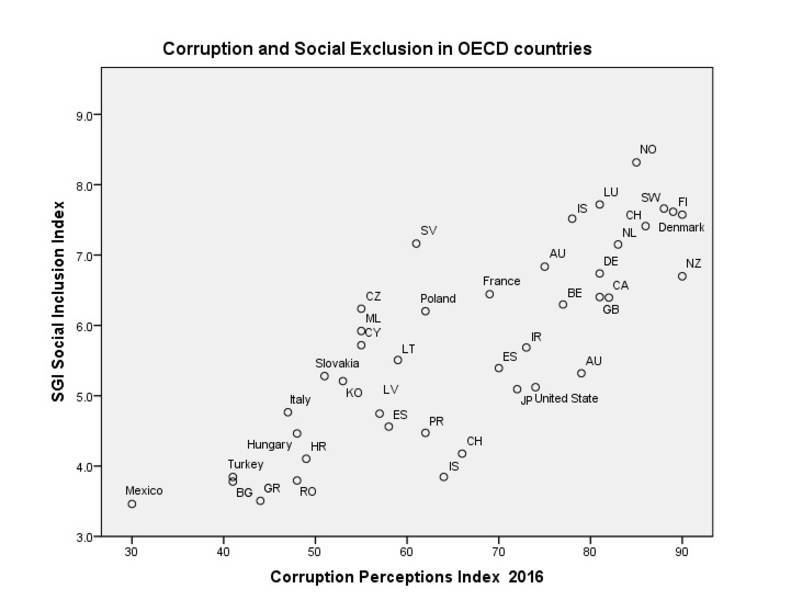

The corruption report was conceived as a part of the European Semester, for multiple studies indicate the direct correlation between corruption and poverty, and in last year’s study of Transparency International and their Corruption Perceptions Index the focus falls on the difficult to disprove data about the connection between corruption and economic inequality, which in itself has been the subject of economic studies for several years now. The plan of the EC was to issue these reports every two years. The document was a great opportunity to come out of mythology and cliché and for member states to look at themselves in this mirror of sorts, as well as learn from each other’s experience. Moreover, this report supported another effort of the previous Commission – to uphold the rule of law, which is set as a key European value in Article 2 of the Treaty for the EU, through the rule of law mechanism, proposed by the EC Vice-President of the time in charge of justice, Viviane Reding (Luxembourg, EPP).

That was a period of serious integration development in an area, which had so far been the “trade mark” for Bulgaria, Romania, and countries in the enlargement process only. Now, three years later, it is plainly seen that the rule of law is seriously threatened in more than one or two member states and the Transparency International index shows a drop in most member states regarding the perception of corruption. The Commission of European veteran Jean-Claude Juncker (Luxembourg, EPP), however, proclaimed itself a political one and bailed out of the battle with member states, regardless of that being one of its key functions – keeping member states in the tracks of the Treaties.

In his letter to Claude Moraes Mr Timmermans admits that corruption is a serious issue in several member states and that it has economic and social significance. In his opinion, however, having corruption clearly mentioned in the country-specific recommendations that the EU issues to member states within the framework of the European semester, makes a separate report like the one from 2014 unnecessary. “Given the complexity and evolving nature of corruption and its prevention, a more efficient and versatile approach would therefore be to complement the continued focus given to corruption issues in the European semester with operational activities to share experience and best practises among Member States' authorities and actively working in a wider context alongside international organisations such as the UN, Council of Europe, the OECD, G7 and others who are engaged in valuable anti-corruption work, as well as private stakeholders and civil society organisations”, is written in the letter in a not-saying-anything administrative language.

It is true that corruption is present in the country-specific recommendations of the member states where this has been identified as a problem, but having 28 member states with a minimum of four recommendations for each obscures the message about the involvement of the EU in general and the EC as a guardian of the Treaties. Moreover, it obscures the big picture, which indicates where these problems are greatest, where they are weakest, and how big is the part in the middle. Adding to all this the fact that member states have pruned down beyond recognition the proposed by Mrs Reading common European mechanism for rule of law, is now bearing its poisonous fruit in the impotent attempts of the EC to bring back Poland onto the right path of a country ruled by law. One more thing – the EC does not issue country-specific recommendations on corruption in Bulgaria and Romania, because this is taken care of by the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM)

In CVM we trust

The sole support of fighters against corruption and rule of law defenders remains the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM), thanks to which Romania is currently making a true anti-corruption revolution of an awe-inspiring magnitude. This is the mechanism, which allowed Bulgaria and Romania to become members of the EU on January 1st 2007, for there was a clear and present danger otherwise that they will become members much later, or never if we consider the later development of the geopolitical situation. This mechanism was a promise to member states from the EC and the two states that they will finalise their transformations from communist, corrupt states into countries ruled by law, based on liberal democracy.

The CVM celebrated a 10-year anniversary on January 1st and champagne is being popped for it in Bucharest, while a requiescat for it is being read in Sofia. On January 25 the EC published its regular reports on the monitoring it does over how the two states perform on their promises. The documents are an attempt to retrospect on the last ten years and they show clearly that so far Romania is winning and Bulgaria is losing. Another thing is also plainly indicated – a clear commitment by the EC to work for the removal of the CVM, despite its own conclusions in the reports. The EC promises in the reports that the Mechanism could be lifted if the recommendations it has defined for the two states be implemented, and to this effect the political part of the report on Bulgaria is clearly done superficially, making it so this goal appears absolutely doable by the end of the year, because Bulgaria is due to, for the first time, take over the rotating presidency of the Council starting January 1st of next year and according to Brussels and Sofia it does not sit well to have the 6-month president be under monitoring for corruption and a dependent judiciary.

Such a position is flawed on several accounts. The first one is that Bulgaria will not be the only presiding state with problems. Hungary took over the presidency several years ago in the very moment when Viktor Orbán had started to dismantle the great transformational success of the Hungarians and build his illiberal regime. This is the very thing the Hungarian presidency was remembered by. The same will not happen with Bulgaria, for the country has been under monitoring for 10 years and to this date there is no reason for this to be the focus of attention over the entire 6 months of its presidency. Such attention will only be drawn in the beginning and remain at that. Another example is Cyprus, which took over the Presidency right after it had negotiated a bailout programme in order to avoid dropping out of the euro area, and Greece presided during the climax of the Greek crisis in the euro area.

Such a position is flawed on several accounts. The first one is that Bulgaria will not be the only presiding state with problems. Hungary took over the presidency several years ago in the very moment when Viktor Orbán had started to dismantle the great transformational success of the Hungarians and build his illiberal regime. This is the very thing the Hungarian presidency was remembered by. The same will not happen with Bulgaria, for the country has been under monitoring for 10 years and to this date there is no reason for this to be the focus of attention over the entire 6 months of its presidency. Such attention will only be drawn in the beginning and remain at that. Another example is Cyprus, which took over the Presidency right after it had negotiated a bailout programme in order to avoid dropping out of the euro area, and Greece presided during the climax of the Greek crisis in the euro area.

Beyond the purely image-defining argument, the very thought of dropping the CVM soon will have catastrophic consequences to Romania mostly, which is currently fighting to turn its great success in the battle against corruption into an irreversible one. This would lend wings to the powers, which have for years sabotaged the truly heroic efforts of the judiciary to preserve its independence and protect taxpayer interests. Removing the monitoring will have a negative effect on Bulgaria as well, where, despite slowly and unconvincingly, there begins to form some serious citizens’ resistance against corruption. And while it is explainable why member states are attempting to get rid of a more serious monitoring on their sins, masking their resistance with the call for upholding national sovereignty, it is inexplicable why the EC is backing down from its main function of guarding the Treaties.

This is Bucharest speaking

The report on Romania is an inspiration for the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism, for it proves it working and bearing fruit. Conclusions in the document are that Romania has so far implemented EC recommendations and this has resulted in a tremendous success. First of all, Romania has managed to successfully complete the much needed judicial reform, making the judiciary fully independent from political influence and has then started amassing accomplishments in the battle against corruption, and at the highest levels of power at that. “The 2016 CVM report also noted signs of a cultural shift in favour of consistency within the judiciary”, is said in the report on Romania. The judiciary is now deeply professionalised. The problem, however, as it has been noted in previous reports (and here), lies in the constant attempts of politicians to undermine its independence and weaken the battle against corruption.

The peak of these efforts came with the decision of the new Romanian government, under an urgent procedure, to practically release from criminal liability a number of politicians convicted for corruption who, due to this reason, are unable to hold any public office. This brought out over half a million Romanians in the streets of Bucharest in temperatures below the freezing point. Pictures of the Romanian protests flew all over the globe and inspired even Americans, who have so far served as major supporter of the battle against corruption worldwide, but after the election of Donald Trump for president, the USA is now being treated as a developing country. Some American senators even joked that the USA needs a president like the Romanian Klaus Iohannis.

Another problem, faced by Romanians in their efforts to make the fight against corruption irreversible are media. A fact noted by the EC for several years in a row now. “The strong media and political attacks on magistrates and the justice system also remain a serious threat to the irreversibility of the fight against corruption”, is said in this year’s report on Romania. Romanian success, regarded one benchmark by benchmark (a total of five), shows the success of the Mechanism and could serve as an inspiration of the transforming power of the EU in countries of the enlargement process, which is suffering from fatigue and even desperation. “The 10 years' perspective of developments under the CVM shows also that, despite some periods when reform lost momentum and was questioned, Romania has made major progress towards the CVM benchmarks”, is one of the report’s conclusions.

Recommendations, however, are very few, which means that certain benchmarks can be closed off. Greatest progress has been made on the one concerning the judiciary. Romania was supposed to build an independent, impartial, and effective system, to boost the consistency of the judicial process, and to enhance transparency and accountability. All this has been accomplished. “These major reforms are nearly finalised”, concludes the EC. The report also contains hidden message to Poland: “The Constitutional Court has played an important role in further development of the rule of law and the consolidation of an independent justice system. Since the constitutional upheaval of 2012, many decisions of the Constitutional Court have contributed to upholding the independence of justice and have sought to provide solutions linked to the balance of powers and respect for fundamental rights that could not be solved by the justice system alone”, says the report.

The Constitutional Court is at the centre of the battle of the European Commission with the government of Poland, which refuses to implement rulings of the tribunal and does whatever it takes to place their own trusted people in the Court, as well as weaken its competences. And as is shown by the fight of American President Donald Trump with the rule of law, independent institutions prove to be the sole obstacle to the state being taken over by authoritarian leaders or private interests.

The second benchmark in the Romanian CVM has to do with the establishment of an integrity agency, which is to check assets, conflict of interests, and issue mandatory sanctions. This benchmark too has been achieved, despite numerous efforts of certain political powers in parliament to weaken the powers of the agency, which has the beautiful female name ANI (Agency for National Integrity). “In line with the recommendation in the last CVM report, ANI also worked closely with the Permanent Electoral Authority in 2016 to ensure that decisions on integrity were carried forward into the eligibility of candidates. This proved effective, with candidates elected in the local elections, despite an integrity ruling, subsequently removed or resigning from office, and with parties and the electoral authorities using the ANI information to avoid ineligible candidates presenting themselves for the parliamentary elections”.

What is left as a task for the agency along the second benchmark is starting to work with the new PREVENT system for preliminary checks for conflict of interests when carrying out public procurement tenders. Romania is excelling in the third benchmark as well, which is linked to the investigation of corruption in the high levels of power. The report acknowledges that the battle against corruption has intensified considerably after the year 2011 and so far results are impressive. The fourth indicator is connected to the prevention of corruption and there is considerable progress made along that one as well.

So, if Romanians win their battle in the streets of Bucharest, it is quite possible that the country will cover all benchmarks, making the CVM obsolete. The question remains, however, how irreversible will that be, keeping in mind the continuing attempts at dismantling the system, which has been put in place with so much effort. The EC believes that this could be solved through establishing internal mechanisms for reporting and accountability, which would begin acting after the CVM is abolished, but is it ready to bet on it working? According to the president of the Council of Europe’s anti-corruption committee (GRECO), Marin Mrčela, who is a judge in the Croatia Supreme Court, the efforts of Croatia have declined rapidly following the accession. Zagreb had decided that the battle has been won and there is no need to fight it anymore.

Romania has accomplished everything Bulgaria has not

Alas, the report on Bulgaria is the absolute opposite of the one for Romania. The benchmarks are 6, but there is no progress on them, despite the attempts of the EC to show this isn’t exactly so. The technical part of the report shows quite clearly what we are talking about. The tenth anniversary of the EC monitoring shows that Bulgaria has so far been working on the principle of some sort of a modified tango, making two steps to the side and one step back. The EC sees several reasons for the slow and winding way of Bulgaria in the fight against corruption.

"However, the pace and depth of reform has necessarily been conditioned by the environment in which the specific issues covered by the CVM can progress, the characteristics of Bulgarian society and its governance. For example, efforts to build administrative capacity in recent years are still under way, having consequences for the reform process. The legislative process in Bulgaria has not provided a predictable legal environment. The Bulgarian media environment is often characterised by low independence and ineffective enforcement of journalistic standards, which has a negative influence on public debate on reforms. While these issues are outside the CVM remit, they have a direct bearing on the ability to deliver reform and have made it more difficult for Bulgaria to make progress", goes the Commission’s diagnose, which hints that not only should there be no talk about removing the CVM, but there should even be talk about expanding it, so that it can encompass more areas which are problematic for the reform.

Beyond this exactness in identifying the problem, in the political part, the Commission is making obvious attempts to mitigate reality, but the contrast with the Romanian report is painfully sharp. The Commission claims that Bulgaria has made considerable progress on the first benchmark, which deals with reforming the judiciary with the goal of establishing a stable constitutional framework for an independent and accountable judiciary. What is pointed out is the two amendments to the Constitution and the Prosecution is singled out as the main obstacle to the process of reforms, but the EC still claims there is considerable progress.

On the second benchmark, which deals with the legal framework of the judicial system and judicial procedures, the EC acknowledges “some” progress, which is a synonym of no progress. The main challenges here are solving the problem of too formalistic procedures and improving the legal framework for the investigation and prosecution of corruption and organised crime. The same lack of progress is seen on Benchmark Three, which focuses on the reform of the judiciary to improve its professionalism, accountability, and efficiency, a thing which is already irreversible with the Romanians, as well as on benchmarks four and five, which deal with the battle against corruption.

Bulgaria shows negligible results in this respect – too few court cases have ended in final convictions regarding corruption at the high levels of power, which, according to the report, is “the clearest way to show that the fight against corruption is a genuine priority”. It is reminded that Bulgaria continues to be the country with the highest level of corruption perception in the entire EU, as is also demonstrated by Transparency International data. The EC reminds that in the first years following its accession Bulgaria had undertaken numerous legislative and institutional measures for dealing with corruption, but those efforts have not brought about the necessary turning point, as it happened in Romania. It is acknowledged that the government has made an attempt in 2015-2016 at the establishment of a single anti-corruption agency, but the bill never made it into Parliament, which is another proof for the lack of political will.

The last benchmark is linked to the battle against organised crime, where the EC acknowledges clear attempts at the removal of this benchmark, for it was a part of the transition and is no longer relevant. According to Bulgarian authorities, organised crime has evolved and currently the problem is comparable to the situation in other member states as well. The EC, however, believes that in this case it is about organised crime transforming into a legal business and the fact that it resorts to violence less frequently. Despite this conclusion, however, the EC recognises considerable progress on the sixth benchmark, regardless of expecting Bulgaria to demonstrate that it does have a functioning system for fighting organised crime through amassing results, represented by final court convictions on cases of serious organised crime, which are being carried out effectively.

The EC believes that the goals of the CVM for Bulgaria can be accomplished through implementing the recommendations in the report. The EC will prepare another report by the end of this year, which will be done in order to avoid publishing a report while Bulgaria is at the helm of the Council.

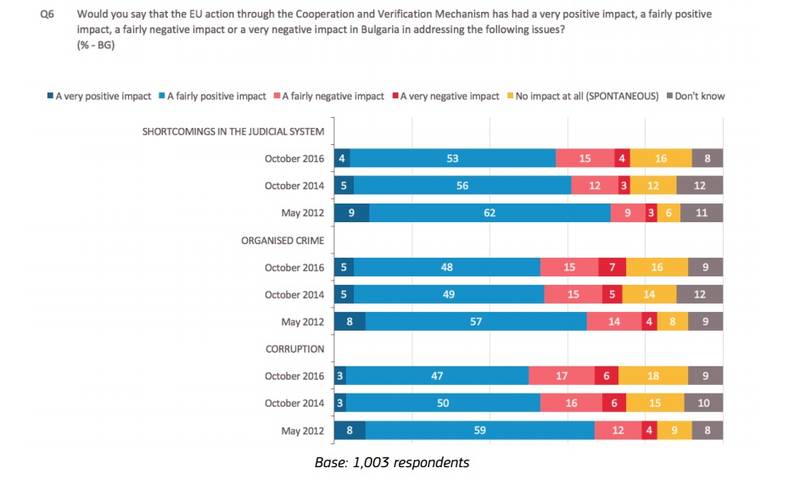

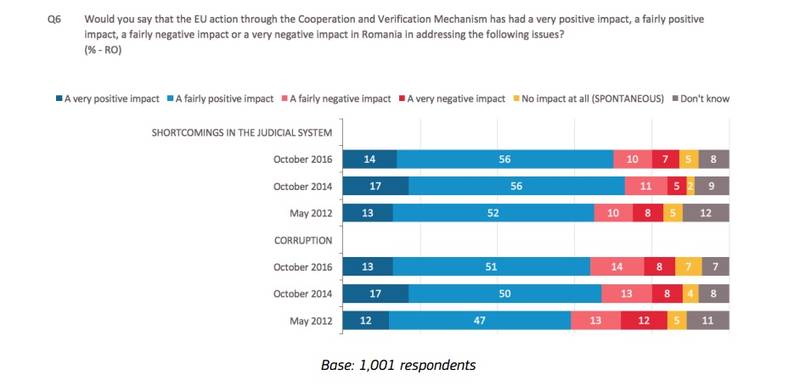

The Eurobarometer survey, which accompanies the reports, shows that support in both countries for continuing work on the CVM remains high. In Romania, 69% of responders want the CVM to continue until Romania achieves alignment with the rest of the member states, and in Bulgaria this percentage is even higher – 72%.

It's education too, stupid!

The president of the Council of Europe’s anti-corruption committee - Croatian Marin Mrčela – in an interview for the Croatian Globus magazine says, however, that the battle against corruption is practically a war which will continue for a long time. He believes this battle should not be limited to the judiciary. “The fight against corruption needs to be in everyone’s focus, not just the judiciary. Judiciary is important, but if we rely on justice alone, we will not achieve the desired results. The judiciary cannot and should not be alone in this fight. The state needs to ensure a thorough battle against corruption, which begins with providing a system for prevention, discovery, and processing of corruption.”

This battle begins in the family, continues in kindergarten, school, and continues throughout life in general, believes the Croatian Supreme Court judge. Moreover, “work is necessary for the eradication of any immoral behaviour, which is not necessarily corruption. If we continue to think it is normal to bring a bottle of strong liquor to the doctor, coffee and chocolates to nurses, same to the referent in the municipality, offer a policeman coffee in return of not issuing a fine; if we find it normal that state-owned businesses hire relatives and friends to those in power, then we need to ask ourselves which are our society’s values and whether we wish to live in such a society. I believe that prevention through education is especially important, the judiciary comes last in line in this battle”, is the recommendation of the leader of GRECO.

The Croatian example is also especially indicative. This is the newest member state, which entered with no monitoring, but following a much stricter accession process. The price to pay was sending a prime minister (Ivo Sanader) to prison, accompanied by several other former ministers. Despite that Mr Mrčela believes that following the accession, the fight against corruption has waned.

According to Transparency International, corruption has contributed significantly to economic inequality and besides, it feeds populism. This year’s report of the organisation says that the new messiahs, who promise a fight against the corrupt elite, are actually part of the problem. “In the case of Donald Trump, the first signs of such a betrayal of his promises are already there. The talk is of rolling back key anti-corruption legislation and ignoring potential conflicts of interests that will exacerbate – not control – corruption”, says the report. Examples are given with Viktor Orbán and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, reminding that Hungary and Turkey have dropped in the corruption perception index since the election of populist leaders.

All this shows very clearly that the EC more than ever – much more than in 2014 – needs to show strong commitment to the fight against corruption in the entire EU. Not just to protect itself as a community of countries ruled by law and a space of liberal values, but also in order to restore its image of a transforming power, which will give the Union the place it deserves in the new geopolitical order. The EU backing away from such a fundamental battle will create a vacuum, which will have catastrophic effects on the Union, its economy, and last but by no means least – on its citizens.

Translated by Stanimir Stoev

Entrance to the Berlaymont building | © EC - Audiovisual Service

Entrance to the Berlaymont building | © EC - Audiovisual Service | © European Union 2020, EC - Audiovisual Service

| © European Union 2020, EC - Audiovisual Service Commission President Ursula von der Leyen | © European Union 2019 - Source: EP

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen | © European Union 2019 - Source: EP