Bulgaria Can Achieve Convergence with EU Average Income by 2040

Adelina Marini, May 30, 2012

In Bulgaria we are constantly measuring our membership in the European Union by income. There was even a risk to apply the Hungarian idea for a sharp wage increases in order to fill in the gap with EU average, thus making accession softer. A mistake that Hungary is currently paying for dearly. But Bulgaria as well did not draw the right lessons from the pre-crisis structure of its economy, as well as from the post-crisis developments. This is a conclusion that comes to mind after reading the IMF's working paper for Bulgaria, entitled "Productivity Growth and Structural Reform in Bulgaria: Restarting the Convergence Engine", published in mid-May. Authors of the document are Pritha Mitra and Cyril Pouvelle.

In Bulgaria we are constantly measuring our membership in the European Union by income. There was even a risk to apply the Hungarian idea for a sharp wage increases in order to fill in the gap with EU average, thus making accession softer. A mistake that Hungary is currently paying for dearly. But Bulgaria as well did not draw the right lessons from the pre-crisis structure of its economy, as well as from the post-crisis developments. This is a conclusion that comes to mind after reading the IMF's working paper for Bulgaria, entitled "Productivity Growth and Structural Reform in Bulgaria: Restarting the Convergence Engine", published in mid-May. Authors of the document are Pritha Mitra and Cyril Pouvelle.

As a sharp contrast to the constant boasting of the government that against the backdrop of the eurozone crisis and the general economic situation of many EU member states Bulgaria looks like an island of stability, the data of the authors show something else - there could be fiscal discipline but there are no conditions to restart growth. And as we started with income, the judgement of the document is: "If Bulgaria were to achieve sustained productivity growth of 4¼ percent per year until 2040, convergence to Portuguese income levels (the lowest of the original euro area members) would be possible". As you know, Portugal is one of the three countries at the moment, in the eurozone, which are under rescue programmes of the IMF and the EU in order to avoid default precisely as a result of low productivity and weak competitiveness.

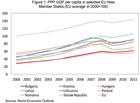

Deposition of myths

Bulgaria suffers a lot for the years of wild economic growth before the 2008 crisis but the analysis of Pritha Mitra and Cyrille Pouvelle makes it clear that this type of  growth was meaningless. The country did not manage to take advantage of the economic boom and catch-up with its peers, called in the document "emerging Europe" (those are the new member states, who joined the EU in 2004 and later) in terms of income per capita. The comparison among the new member states in the EU shows that, although it was the poorest in 2000, Bulgaria did not experience faster growth in its PPP GDP per capita in the following decade. The same fate is shared by Romania as well. For this reason the income gap with the other new member states has remained the same and even increased with countries that went through a severe recession in 2007, like Latvia for instance.

growth was meaningless. The country did not manage to take advantage of the economic boom and catch-up with its peers, called in the document "emerging Europe" (those are the new member states, who joined the EU in 2004 and later) in terms of income per capita. The comparison among the new member states in the EU shows that, although it was the poorest in 2000, Bulgaria did not experience faster growth in its PPP GDP per capita in the following decade. The same fate is shared by Romania as well. For this reason the income gap with the other new member states has remained the same and even increased with countries that went through a severe recession in 2007, like Latvia for instance.

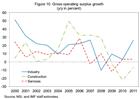

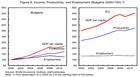

Against this background, the crisis contributes additionally to the deterioration of the situation. After the booming years and jobs creation in the pre-crisis period, the Bulgarian economy is in a difficult period, according to the authors of the document. The crisis has led to a massive loss of jobs, even more than were created before the crisis. From the beginning of the crisis up to the end of 2011 employment in Bulgaria has dropped by 12%, the analysis points out. As a real number, this loss represents 133,000 jobs per year, compared to the 100,000 jobs created during the boom. However, here Bulgaria is not the worst performer in the group of the new EU member states, but it is facing a heavy challenge because for the regional standards (the new member states) recovery from the crisis is weak. If gross domestic product starts to grow by 2 per cent annually, 10 years will be needed in order the reach the pre-crisis levels of employment of 5.6%, the report states. For now there is no possibility for this to happen - for 2012 the forecast is for growth of less than 1%.

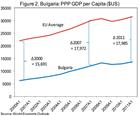

In spite of the impressive economic boom before the crisis, the scissors of GDP per capita between Bulgaria and the EU average remain wide open. In 2011 the difference was around 13,800 euro. The process of convergence gets additionally complicated by the melting working force as a result of ageing population (which for its part has an effect on the future growth of GDP) and emigration. For the decade 2000-2010 the population in working age has dropped by 7.7% but what is worse is that it is expected to decline by further 18.9% (compared to 2000) by 2025.

In spite of the impressive economic boom before the crisis, the scissors of GDP per capita between Bulgaria and the EU average remain wide open. In 2011 the difference was around 13,800 euro. The process of convergence gets additionally complicated by the melting working force as a result of ageing population (which for its part has an effect on the future growth of GDP) and emigration. For the decade 2000-2010 the population in working age has dropped by 7.7% but what is worse is that it is expected to decline by further 18.9% (compared to 2000) by 2025.

Most severe is the problem with youth unemployment, which is a problem for the entire EU, as euinside wrote recently. According to the IMF working paper, the risk of long-term unemployment among the young people in Bulgaria is high. In 2011, the number of young unemployed has increased to 26% (double to 2008 levels). Although this phenomenon is not alien to other new EU member states, in Bulgaria the situation is a bit harder which suggests, according to the authors, that the newcomers on the labour market do not possess the necessary skills to be competitive. Moreover, this could be a signal of a dual labour market. And this leads to an outflow of working force. The brain drain to the rest of the countries in Europe has a 6.7% share in the general decline of the work force since 2008 to date. The report quotes data, according to which 16 per cent of the population has emigrated in 2010 and further 20 per cent are ready to do that.

It's the education, stupid!

The authors recall again that the solution of the problem is investments in education, innovation, infrastructure and fight against corruption. The main engines of economic growth are summarised in the working paper in 11 categories: institutions, infrastructure, financial market development, goods market efficiency, health and primary education, higher education, innovation and sophistication, labour market efficiency, macroeconomic environment, market size, and technological readiness. If Bulgaria increased the standards and reaches the EU average in each of these 11 ![]() categories, this would contribute to a real increase of productivity by 1 percentage point. The biggest share will have increasing the quality of infrastructure and goods market efficiency, as each of these two categories will bring one third percentage point to productivity growth.

categories, this would contribute to a real increase of productivity by 1 percentage point. The biggest share will have increasing the quality of infrastructure and goods market efficiency, as each of these two categories will bring one third percentage point to productivity growth.

Similar achievements can be expected with targeted investments in higher education, innovation and institutions. Although many of the categories that would bring to increasing labour productivity are written as objectives in Bulgaria's National Reforms Programme for the period 2011-2015 and in the Bulgaria 2020 strategy, the authors focus on improving the quality of higher education as through immediate, so by long-term measures. This could happen by creating a centralised computer matching services and more targeted vocational, technology and language training programmes.

Improving goods market efficiency means targeted administrative reforms. Example for such reforms could be facilitating customs procedures, cutting red tape and facilitating entry on the market. Bulgaria suffers from a lack of technological absorption capacity. This could be compensated to some extent by improving public-private relations. In that area, as with education, it is recommended a more efficient use of the EU funds, which precisely in this sphere (and for the implementation of the Europe 2020 strategy goals) will obviously keep their size and might even be increased in the next programming period.

![]() Huge investments are needed to improve the quality of infrastructure. This point is very important because it emphasises on the word 'quality'. In the report it is pointed out that poor infrastructure increases significantly the operational costs of the firms and hampers labour mobility and trade. Besides, it is an obstacle for Bulgaria's role as a conduit for trade, for example between Turkey and the EU. In the document the ongoing work on important motorways, such as Trakia and Struma, is mentioned, the construction of bridges and the modernisation of railways with EU money, but it is recommended special attention be paid on how important it is to maintain macro economic stability under a currency board. The idea behind this

Huge investments are needed to improve the quality of infrastructure. This point is very important because it emphasises on the word 'quality'. In the report it is pointed out that poor infrastructure increases significantly the operational costs of the firms and hampers labour mobility and trade. Besides, it is an obstacle for Bulgaria's role as a conduit for trade, for example between Turkey and the EU. In the document the ongoing work on important motorways, such as Trakia and Struma, is mentioned, the construction of bridges and the modernisation of railways with EU money, but it is recommended special attention be paid on how important it is to maintain macro economic stability under a currency board. The idea behind this  message is to beware avoiding in the name of improving infrastructure excessive increases of the budget deficit.

message is to beware avoiding in the name of improving infrastructure excessive increases of the budget deficit.

Interestingly, here special attention is paid to the plans for quality monitoring and maintenance, obviously with the aim to avoid squandering public money for the sake of fast but not well done work, which will not solve the main issue mentioned above - to ensure labour mobility, to reduce the operational costs of the firms and to facilitate trade.

Although the reforms in the judiciary are put as a last point, according to the authors they will significantly improve the institutional challenges the business is facing. For its five years of EU membership Bulgaria has not succeeded in taking advantage of the strong shoulder the EU gave the country allowing it to join the union without having completed the process of reforms. This is why the country entered the union with a crutch - the Control and Verification Mechanism in

Although the reforms in the judiciary are put as a last point, according to the authors they will significantly improve the institutional challenges the business is facing. For its five years of EU membership Bulgaria has not succeeded in taking advantage of the strong shoulder the EU gave the country allowing it to join the union without having completed the process of reforms. This is why the country entered the union with a crutch - the Control and Verification Mechanism in  the area of justice and home affairs, on which the Commission is expected to come up with a huge report this summer, summarising the work of the mechanism so far and offering guidelines for the future. More specifically in terms of productivity and economic growth, the report of the authors from the IMF recommends creation of Internet portals for the district courts, posting time to resolution of each case and decisions which would increase transparency. It is also recommended more effective and less costly enforcement of contracts which will also reduce the number of firms breaching contracts.

the area of justice and home affairs, on which the Commission is expected to come up with a huge report this summer, summarising the work of the mechanism so far and offering guidelines for the future. More specifically in terms of productivity and economic growth, the report of the authors from the IMF recommends creation of Internet portals for the district courts, posting time to resolution of each case and decisions which would increase transparency. It is also recommended more effective and less costly enforcement of contracts which will also reduce the number of firms breaching contracts.