The Polish Amendment in the New Fiscal Treaty

Adelina Marini, Ralitsa Kovacheva, February 2, 2012

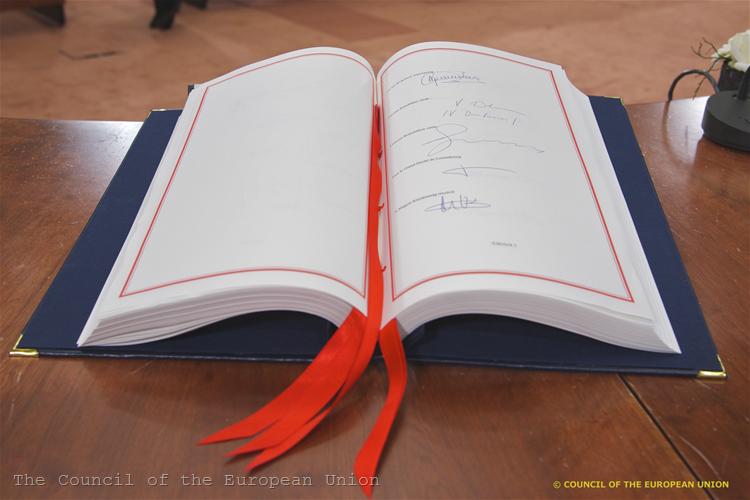

On the 1st of March 2012 25 out of 27 EU member states will sign the new Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), the so called fiscal compact. Without so much drama and much faster than expected, on Monday evening ended the informal European Council, whose main purpose was to finalise the text of the treaty, the drafting of which took a little more than a month. Although it was envisaged the summit to last some 4 hours, the expectations of journalists and analysts were for it to continue until the early hours of the next day, as it happened in December. From the adopted text it becomes clear though, that in fact the most disputed point was only one, the rest is just cosmetic changes.

On the 1st of March 2012 25 out of 27 EU member states will sign the new Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), the so called fiscal compact. Without so much drama and much faster than expected, on Monday evening ended the informal European Council, whose main purpose was to finalise the text of the treaty, the drafting of which took a little more than a month. Although it was envisaged the summit to last some 4 hours, the expectations of journalists and analysts were for it to continue until the early hours of the next day, as it happened in December. From the adopted text it becomes clear though, that in fact the most disputed point was only one, the rest is just cosmetic changes.

The Polish Amendment

You probably remember that first crucial European Council in October when there were a lot of predictions about how many days of life remain for the euro and so on? That same Council, during which there was a precedent. In the pause between the summits of the eurozone and the European Council on October 26, instead of the usual speakers - Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso and European Council President Herman Van Rompuy, at the intermediate news conference showed up Polish PM Donald Tusk, whose country at that moment was presiding over the Council of the EU. It was then when the foundations of the Polish amendment were set forth - the countries who have ambition to become part of the euro area to be able participate in its summits.

According to The Financial Times, Polish premier Tusk insisted the participation of non-euro countries in the EMU summits to be guaranteed in the pact. A call, which has obviously been taken into account, given the quite unambiguous and clear tone in the final version of the treaty: "The Heads of State or Government of the Contracting Parties, other than those whose currency is the euro, who have ratified this Treaty SHALL participate in discussions of Euro Summit meetings concerning competitiveness for the Contracting Parties, the modification of the global architecture of the euro area and the fundamental rules that will apply to it in the future, as well as, when appropriate and at least once a year, in discussions on specific issues of implementation of this Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union".

This means, as later Mr Van Rompuy explained, that whenever these countries join  the eurozone, and they are obliged to do so, they will abide with the same rules in the creation of which they had participated. As the amendment is indeed important and it is entirely to the merit of Poland, with the cooperation of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia (in spite the fact that the Czechs remained outside the treaty), it is most appropriate that this is called the Polish Amendment.

the eurozone, and they are obliged to do so, they will abide with the same rules in the creation of which they had participated. As the amendment is indeed important and it is entirely to the merit of Poland, with the cooperation of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia (in spite the fact that the Czechs remained outside the treaty), it is most appropriate that this is called the Polish Amendment.

The concessions to the European Parliament

Although he was visibly not satisfied after his first participation in a European Council, the new president of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz, should feel happy. At his news conference on Monday night he expressed his discontent with the  fact that in the treaty it is envisaged that the European Parliament president "may be invited" to take part in the euro area summits. According to him, this was not about himself as a person, but about the Parliament as an institution which is a co-legislative body. Indeed, the parliament's president participation is enshrined in the conditional mood but unlike the fourth draft accountancy is guaranteed after the eurozone summits before the MEPs:

fact that in the treaty it is envisaged that the European Parliament president "may be invited" to take part in the euro area summits. According to him, this was not about himself as a person, but about the Parliament as an institution which is a co-legislative body. Indeed, the parliament's president participation is enshrined in the conditional mood but unlike the fourth draft accountancy is guaranteed after the eurozone summits before the MEPs:

"The President of the Euro Summit shall present a report to the European Parliament after EACH of the meetings of the Euro Summit".

The Treaty

As euinside wrote a number of times, the purpose of the new treaty was circumvent Britain's resistance for amendments to the existing EU legislation or, as PM Cameron put it - against a new EU treaty. The purpose of the new treaty is the EU countries to undertake stricter commitments for budget discipline, to enhance coordination among themselves, so that it can reflect the real interconnectedness of  their economies and, most of all, to increase the eurozone's stability and to boost economic growth. The essence of the fiscal discipline is laid out in a special chapter in the treaty, called Fiscal Compact.

their economies and, most of all, to increase the eurozone's stability and to boost economic growth. The essence of the fiscal discipline is laid out in a special chapter in the treaty, called Fiscal Compact.

The contracting parties commit themselves to balance their budgets and to strive for surpluses, as the permissible deviation from the mid-term objective is 0.5% of GDP of structural deficit on market prices. The foreseen up to the moment exemptions are kept in the final text too, as it is stated that these rules would not be applied in cases of extraordinary circumstances, which are beyond control of the country in question. The Treaty also envisages incentives for disciplined countries, which was a major requirement of countries like Bulgaria, who said that fiscal disciplined countries should not be punished for abiding to the rules. For them it is envisaged, if their debt is much below the ceiling of 60% of GDP, to be able to make a higher than 0.5% structural deficit but no more than 1.0 per cent.

Another important part of the fiscal compact is the correction mechanism which will be triggered automatically in case of "significant deviation from the mid-term objectives". In the final text of the treaty the possibility a participant country to decide on its own whether to undertake corrective actions is excluded. On the contrary, it is said that every country that has deviated is OBLIGED to undertake corrective measures in a specified period of time. There is a small but important detail added to the final text - the corrective actions will be applied in the cases of extraordinary circumstances too. There is a new text added to this point, according to which "the existence of an excessive deficit due to the breach of the debt criterion will be decided according to the procedure set forth in Article 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)".

This article gives the Commission power to supervise the budget situations and the government debt of the member states and to identify significant errors. It is also envisaged the Commission to propose the imposition of financial sanctions. In the new treaty another very important thing is envisaged - a contracting party can signal with the European Court of Justice if it deems that another participant country does not stick to its commitments. The decisions of the court are legally binding and if not applied to the country in breach could be fined. The novelty in the final version of the text is that if a participating country decides that another has not undertaken the necessary measures to comply with the court's decision, it can again raise the matter with the court and require the imposition of financial penalties according to criteria of the Commission, described in detail in Article 260 of TFEU.

This article gives the Commission power to supervise the budget situations and the government debt of the member states and to identify significant errors. It is also envisaged the Commission to propose the imposition of financial sanctions. In the new treaty another very important thing is envisaged - a contracting party can signal with the European Court of Justice if it deems that another participant country does not stick to its commitments. The decisions of the court are legally binding and if not applied to the country in breach could be fined. The novelty in the final version of the text is that if a participating country decides that another has not undertaken the necessary measures to comply with the court's decision, it can again raise the matter with the court and require the imposition of financial penalties according to criteria of the Commission, described in detail in Article 260 of TFEU.

A fine cannot exceed 0.1% of the country's GDP and if it is a eurozone member the money from the penalty will be paid directly to the permanent rescue fund - the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). In the rest of the cases, the payments will go to the common EU budget.

Another important element in the treaty is Chapter IV, considered as extremely dangerous in Bulgaria. This is the chapter which envisages coordination of economic policies and convergence. The tone in it is not that unconditional as in the previous version and is more or less wishful. If before it was said that the contracting parties and especially those who share the common currency agree to undertake specific measures for enhanced cooperation on issues that are of great importance for the smooth functioning of the eurozone, but without undermining the single market, in the final text it is shown that these countries stand ready to use specific measures in this direction.

There is another substantial change in the text and it is related to those countries that wish to join the treaty at a later stage. If before it was envisaged a willing country to file an application and wait for the approval of all contracting parties, now it will be enough only to file application. As far as it becomes clear from the agreement at the European Council outside the treaty remain only Britain and the Czech Republic, which really makes it useless to make them apply under a complex procedure.

After the treaty is ratified on March 1 it will enter into force on the 1st of January  2013 if ratified by 12 countries. The full text of the treaty will enter into force from the day the ratification instruments of 12 countries are deposited but only for the eurozone countries, while the rest can apply only certain parts of Chapters III and IV until their accession to the EMU - the fiscal compact and the coordination of economic policies. After the ratification, the countries have to transfer the treaty into their national legislation, preferably at a constitutional level, but not later than a year after that.

2013 if ratified by 12 countries. The full text of the treaty will enter into force from the day the ratification instruments of 12 countries are deposited but only for the eurozone countries, while the rest can apply only certain parts of Chapters III and IV until their accession to the EMU - the fiscal compact and the coordination of economic policies. After the ratification, the countries have to transfer the treaty into their national legislation, preferably at a constitutional level, but not later than a year after that.

By the way, the constitutional element was another point which Martin Schulz heavily criticised. According to him, there are not many countries that have majorities sufficient to change the constitution so that the treaty provisions could be adopted.

It was evident on Monday night that at this first European Council for this year the wishes of all have been satisfied as much as possible. The interesting part will begin during the ratification process. For now the financial markets react well, but the practise in the last 2 years shows that this is never a reason for calm.

| © The Council of the European Union

| © The Council of the European Union | © www.parliament.bg

| © www.parliament.bg | © The Council of the European Union

| © The Council of the European Union | © euinside

| © euinside | © EU

| © EU | © EU

| © EU