The Netherlands Is Afraid of Low-Qualified Bulgarians

Adelina Marini, February 3, 2014

If it were not for the Iron Curtain, for sure Bulgarians and Romanians, but also Slovaks, Czechs, Poles and all the others for whom the Berlin Wall was an obstacle in front of their economic and individual freedom, would not have been the poor relatives who endanger the wellbeing of their western cousins with their desire for better life, better pay and more possibilities for work. If the Iron Curtain never existed, most probably a Eastern European would not have been a synonym of poor, corrupt, but in most cases well educated person. And last but not least, if it were not for the curtain, the European West would have not been forced to seek cheap labour in Turkey and the African Mediterranean, but would, rather, have used the culturally closer relatives in Eastern Europe. However, the curtain was there and it was doing its devastating job for decades.

If it were not for the Iron Curtain, for sure Bulgarians and Romanians, but also Slovaks, Czechs, Poles and all the others for whom the Berlin Wall was an obstacle in front of their economic and individual freedom, would not have been the poor relatives who endanger the wellbeing of their western cousins with their desire for better life, better pay and more possibilities for work. If the Iron Curtain never existed, most probably a Eastern European would not have been a synonym of poor, corrupt, but in most cases well educated person. And last but not least, if it were not for the curtain, the European West would have not been forced to seek cheap labour in Turkey and the African Mediterranean, but would, rather, have used the culturally closer relatives in Eastern Europe. However, the curtain was there and it was doing its devastating job for decades.

Two decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the Iron Curtain, the romantics of the unification of the Continent has disappeared to give ground to the need of a new curtain. Fortunately, at least for now, not an iron one, as euinside recently wrote, but, still, a curtain. The European West has managed to swallow eight eastern European states and most of all the Polish plumber, but choked with the Bulgarian and Romanian low-qualified workers and especially the Roma, who are now free to work and live everywhere in the EU as of January 1st. This has unleashed a wave of, at times, loutish hysteria in Britain which will have long-term impact on the perception of Bulgarian and Romanians in general, but also of the European idea at large.

The problem is though, that the concerns of a Bulgarian-Romanian invasion are not only British. There are worries in The Netherlands, too, which has often played lately in the anti-integrationist choir with the United Kingdom. Fortunately, the Dutch debate is not at the level of the British hysteria, but the problem is being taken seriously and especially with a focus on the Bulgarians, not as much the Romanians.

Last week, the Dutch independent think-tank Dutch Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR) published a study which outlines the problems, but also offers solutions. Although it shows that the big danger did not happen on January 1st, as expected, it is clearly said that there is justification of concern. Justification stems mainly from the low qualification of the Bulgarians. A comparison is made to the consequences of the reception in the 1960s and 1970s of many guest workers from Turkey and Morocco who later were left without work thus creating tensions socially. In The Netherlands, since 2004 (the big bang enlargement), there are some 340 000 migrants from Central and Eastern Europe. In spite of the existing labour restrictions that were valid until December 31st 2013, it is supposed that there are between 34 000 and 44 000 Bulgarians in the Netherlands and between 62 000 and 72 000 Romanians.

They entered the country as self-employed, students, with working permits or as illegal workers. WRR suggests that the Romanian-Bulgarian presence will become more visible this year because the migrants will be able to reside completely legally. To make the picture clearer, the Netherlands's population, according to Eurostat data, is almost 16.8 million people. Employment is amongst the highest in the EU - 71.9%.

Pros and cons of the Bulgarian-Romanian labour migration

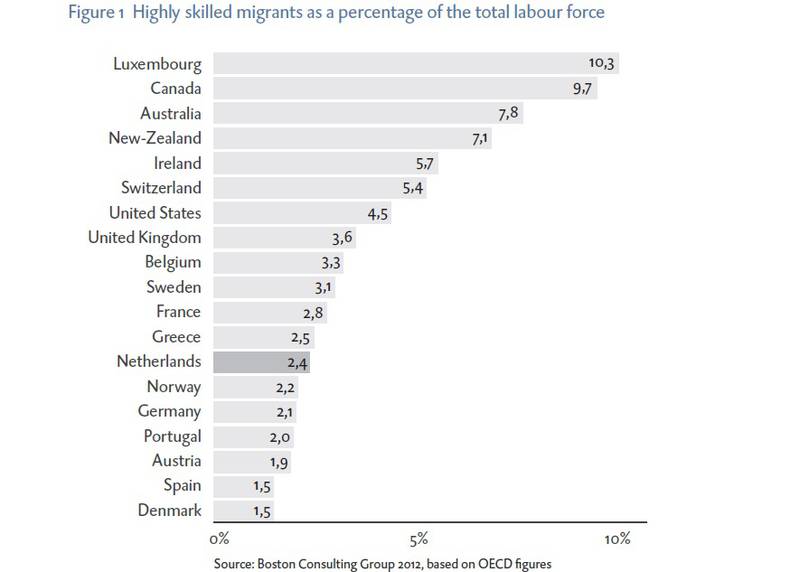

According to the study, temporary labour migrants from Central and Eastern Europe in the Netherlands are viewed the most positively because they bring net contributions of 1,800 euros per person annually. The benefits are multiplied by the fact that the European migrants pay taxes and rarely use welfare benefits. At this stage, there is no empirical evidence to confirm fears of European benefits tourism. In its study, the WRR notes, though, that the Dutch welfare system is prone to fraud. The problem is, however, that at this stage the Netherlands is attracting mainly low-qualified migrants. For instance, one fifth of the labour migrants in the country are low-qualified, while the specialists are a little more than 2% of the entire work force.

And although today's European labour migrants are much more qualified than the guest workers in the past century, a significant part of them is at the bottom of the labour market and take the so called "flexible jobs" - temporary contracts. This is especially valid for the Bulgarians, who already are in the Netherlands, the think-tank claims. On average, the Bulgarians have much lower educational level than the Bulgarians in Bulgaria itself, WRR believes. The Romanians are in a bit more favourable light because they seem to have higher educational level. However, the Roma people both from Romania and Bulgaria have too low or now education at all. That is why, WRR recommends the Dutch government to focus its policy on education and integration in the Dutch society.

Currently, there are whole cities and villages in the Netherlands with high concentration of new, mainly low-qualified, Europeans, many of whom speak almost no Dutch. Among them, the Turkish-Bulgarian group is in the most "worrying" situation because it is at the bottom of the income staircase and practically is moving entirely within the informal employment. Such cities are Rotterdam and the Hague, but also small areas in the Noord-Brabant and Limburg provinces.

In the WRR study, it is also pointed out that apart from the low-qualified Bulgarians and Romanians, most of all Roma, a potential problem are also the students and those who work for multinational companies. The aspects, though, are different. The low-qualified are a problem from the point of view of their burden on the welfare system and are also a prerequisite for tensions, while students are viewed as potential The Netherlands is willing to keep. The Eastern Europeans who work in multinationals in the country put the Dutch citizens on an unequal footing. After Germany, China and Belgium, Bulgaria is the fourth most important country of origin of foreign students in the Netherlands. Currently, they are 1,600, while in 2007-2008 they were 711. The number of Romanian students is also significant, but less than the Bulgarians - 1,050. Most students return to their home countries, most of all the Bulgarians, who do not feel at home in the Netherlands. This, though, is a problem for the country.

It is a problem in a broader European perspective because the Netherlands needs highly qualified workers, but WRR recognises that Bulgaria, too, needs them. Moreover, the country has been suffering a severe brain-drain for the past years. Bulgarians and Romanians are attractive for The Netherlands because 21% of the Bulgarians and 12% of the Romanians have high qualifications, but only 11% of the  Bulgarian and 2% of the Romanian specialists work at their educational level. The phenomenon is known as a "brain-waste" and is known not only in The Netherlands.

Bulgarian and 2% of the Romanian specialists work at their educational level. The phenomenon is known as a "brain-waste" and is known not only in The Netherlands.

The Eastern Europeans, who work in The Netherlands through a multinational company, put the Dutch themselves on an unequal footing because they pay their welfare contributions at home and they are generally much lower than the Dutch contributions. That is why, these companies avoid hiring Dutch for whom welfare spending is sensibly higher.

WRR proposes several interesting ideas that can be supplemented by solutions at EU level too. One of the ideas, for instance, is the countries that are most often targets of labour migration, to invest in the countries of origin. The investment could be in their health care systems or in technical education because the study says that 7% of Romanian doctors have emigrated. Also a possibility is to ensure that part of the specialists will return home but will keep their links with The Netherlands. Thus knowledge networks will be created that could seriously boost the economic benefits from labour migration for The Netherlands.

WRR believes that there is sufficient ground for action and cooperation in the social-economic area on the integration of low-qualified Roma people, including their return home if measures do not deliver. The think-tank believes that the contacts between the Dutch government, Bulgaria and Romania should not be restricted to the recently concluded labour agreements only. Also important is to develop broader, knowledge-based economic relations between the host countries and the countries of origin. An option is also the exchange of mid-level technical staff, partnerships between universities and other scientific networks. Locally, investment in integration of Bulgarians and Romanians from the low bottom of the labour market is proposed through language education and training which will ensure that in the longer term they will have less chances to remain off work.

However, all this cannot and should not be resolved at a bilateral level only because the market, with all its restrictions and flaws, is quite common European market. That is why, the conclusion of a labour pact shold be considered that could help prevent and even restore to some extent the brain-drain in the poorest member states. And since the eurozone crisis, those are not at all only Bulgaria and Romania. There are also indications of a brain-drain in Greece, Spain, Portugal, Ireland. Very often, this process is the result in many cases of bad governance and to a much smaller extent to external economic circumstances. That is why the solution could be sought at EU level in improving governance in the poorest countries that have not done sufficient structural reforms or that have issues with the rule of law and corruption.

With the latter, it could be thought of redirection of EU funds toward the health care and education systems to motivate specialists stay at home or even return home. And as in the education system often the problem is mentality or culture that hamper radical transformation, EU funds could finance the "import" of teachers in Bulgaria and Romania to significantly increase the quality of education, especially in the early stages of schooling and also to enable the system to open up to change. It is true that the multiannual financial framework is already approved as are most of the national programmes, but for sure countries like UK or The Netherlands could initiate changes to avoid tensions stemming from labour migration. After all, this is a problem that has for quite a long time been underestimated and currently is the biggest threat to European integration because it is a byproduct of the slow pace of economic convergence. The most important thing however, will be to avoid closing the single market which is anyway not sufficiently open.

Federica Mogherini | © Council of the EU

Federica Mogherini | © Council of the EU | © Council of the EU

| © Council of the EU Luis De Guindos | © Council of the EU

Luis De Guindos | © Council of the EU