How to make better the things people really care about?

Ralitsa Kovacheva, Angel Shoilev Junior, January 24, 2011

It is not the first time when we openly admire British Prime Minister David Cameron. Not because we just admire everything that comes from abroad or we are tempted by lustrous political speech. It is because David Cameron is about to implement historic reforms in Britain, moreover with a clear vision of purpose and means, with remarkable consistency and strong political rhetoric, which can attract the support of the citizens. Bulgaria too desperately needs such reforms, but our government can neither formulate, nor conduct them with the necessary depth and consistency.

It is not the first time when we openly admire British Prime Minister David Cameron. Not because we just admire everything that comes from abroad or we are tempted by lustrous political speech. It is because David Cameron is about to implement historic reforms in Britain, moreover with a clear vision of purpose and means, with remarkable consistency and strong political rhetoric, which can attract the support of the citizens. Bulgaria too desperately needs such reforms, but our government can neither formulate, nor conduct them with the necessary depth and consistency.

Mr Cameron's speech on the modernisation of public services is worth to read not only because of its content, but also because of its shape. I do not know whether or how many people prepare Cameron’s speeches, but every time I admire his ability to alternate facts with emotions, to hold public's attention to the end, explaining the most complex problems in a simple (not simplistic or vulgar) and understandable manner.

Combined with the non-verbal means of expression, used by David Cameron,  while talking (obviously not having trained before the mirror, as it is often the case with some Bulgarian politicians), his personal presence and obvious emotional commitment to the topic contribute to the success of his public speaking. Not matter if you share his views or not, you cannot say that you have not understood them. And you cannot feel offended as an audience, because someone had treated you as witless idiots, as many Bulgarian politicians do.

while talking (obviously not having trained before the mirror, as it is often the case with some Bulgarian politicians), his personal presence and obvious emotional commitment to the topic contribute to the success of his public speaking. Not matter if you share his views or not, you cannot say that you have not understood them. And you cannot feel offended as an audience, because someone had treated you as witless idiots, as many Bulgarian politicians do.

As regards the content, in his speech Mr Cameron presented a clear and meaningful vision for modernising public services. Because “it’s not that we can’t afford to modernise; it’s that we can’t afford not to modernise”. He reminded his thesis that politics should express people’s interests and needs: “But quite apart from all these practical arguments for modernisation, there’s what I’d call the people argument. If politics is about anything, it’s about focusing on those things people really care about – and making them better.” It is no accident that, before becoming a Prime Minister, Cameron was invited to present his vision as a lecturer at the TED initiative. This policy of more openness, transparency and dialogue was at the heart of all actions, taken by the British government last year.

The government is facing a serious challenge to reduce the budget deficit of 11% of GDP and the serious debt, close to 70% of GDP. For this purpose, they announced drastic cuts in public spending and half a million people will be sacked from the public sector. In such conditions, the modernisation of public services, aimed at more efficient use of resources, seems the only solution, moreover this will increase their quality.

In order not to speak just about some faceless services and servants, David Cameron explained who these people were and why their job was so important: “The doctors who cared for my eldest son [Ivan died in 2009 aged just 6], the maternity nurses who welcomed my youngest daughter into the world, the teachers who are currently inspiring my children all of them have touched my life, and the life of my family, in an extraordinary way and I want to do right by them.”

In order not to speak just about some faceless services and servants, David Cameron explained who these people were and why their job was so important: “The doctors who cared for my eldest son [Ivan died in 2009 aged just 6], the maternity nurses who welcomed my youngest daughter into the world, the teachers who are currently inspiring my children all of them have touched my life, and the life of my family, in an extraordinary way and I want to do right by them.”

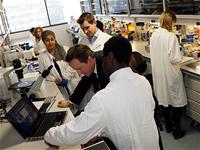

The PM criticised the simplistic understanding that the private sector paid for the public one - which is very popular in our country too: “Parts of the public sector help generate innovation and wealth more directly like our teaching hospitals and universities which, can be one of the great wealth creating engines of the 21st century, knowledge based economy.” But to fulfill its true purpose and we, who use it, to appreciate it, the public sector needs to change. How? By being "freed" and encouraged to develop itself.

From the very beginning David Cameron refuted the allegations that all costs for the public sector would be cut. The state will continue to pay for it 41% of GDP. It will continue to pay 5,000 pounds a year for the education of every child in the country, which, according to Cameron, is like in Germany and more than it is being paid in France. Police officers will continue to be as much as their colleagues in New York are and the budget of the National Health Service will be increased to the average for Europe. Because “the quality of care we offer in our health service is a measure of the country we are. The quality of education we offer our children is a measure of the country we can become.”

That's why the British PM pays attention to the goals that are not measured by  money. For example, improving discipline in schools or more stringent standards in evaluating students. This requires teachers to be more prone to initiative and to have more freedom to make decisions of their own. What does the British government? It gives them this freedom: less bureaucracy, less centralised instructions, less state in public services. Because they are for the people, not for the government.

money. For example, improving discipline in schools or more stringent standards in evaluating students. This requires teachers to be more prone to initiative and to have more freedom to make decisions of their own. What does the British government? It gives them this freedom: less bureaucracy, less centralised instructions, less state in public services. Because they are for the people, not for the government.

The state should not tell the public sector professionals what to do, but to encourage them to make the best of themselves and to take responsibility for their actions, by tying payments to results. But far from the case that the elimination of centralised control will leave the public sector without proper accountability. It will now be responsible to the society which uses its services and pays for them. “So we are spreading choice, saying to any parent or patient: you can choose where your child gets sent to school or where to get treated and we’ll back that decision with state money.”

Moreover, the whole society must be engaged in this process. For example: “For the first time, charities, universities, businesses, teachers and groups of parents will be allowed to establish their own academies where there is a lack of suitable education for 16-19 year olds.” But society not as being some abstract concept, but in terms of specific groups of people with common purposes and actions must become the focus of public services, because this is their primordial function.

It was the loss of this focus that had made the public sector a separate mastodon, sucking public funds without returning adequate benefit to society, for which, of course, responsible were mainly politicians: “The right were guilty of focusing too much on markets. The left were guilty of focusing too much on the state. Both forgot that space in between – society.”

Where is the role of the government? To create and control the rules of the game, of course. “The state has a hugely important responsibility to ensure clear, basic standards are met, the rights of users are maintained and independent inspection is carried out in our public services.”

Obviously in the UK, as in Bulgaria, many people abuse causes such as “fairness” and “social justice” to criticise such reforms, as it is clear from the speech of the British Prime Minister. In such criticism, however, he sees an attempt “to prevent any innovation or progress that could allow one child or one school to do better than another”. And this is exactly the meaning of the policy pursued by the British government - for more competition and race for improvement in which everyone can learn from the best practices of others. “There’s a simple logic to all this: with more freedom and openness comes more creativity and innovation.”

Whether the plans of the British government will bear the expected results will become clear in the years to come. What is apparent now, however, is the vision: freedom, innovation, initiative, responsibility, commitment. Count how many times you will find these words in the statements of the Bulgarian Prime Minister. Count how many times you will hear them on television. Ask several children in a school yard if they know what these words mean. Politics, says Cameron, is to make better the things that people really care about. We owe it to ourselves to learn Bulgarian politicians do this.

Whether the plans of the British government will bear the expected results will become clear in the years to come. What is apparent now, however, is the vision: freedom, innovation, initiative, responsibility, commitment. Count how many times you will find these words in the statements of the Bulgarian Prime Minister. Count how many times you will hear them on television. Ask several children in a school yard if they know what these words mean. Politics, says Cameron, is to make better the things that people really care about. We owe it to ourselves to learn Bulgarian politicians do this.

Krasimir Valchev | © Council of the EU

Krasimir Valchev | © Council of the EU | © euinside

| © euinside | © EU

| © EU