Russia and Turkey: Enemies in the Past, Conscious Partners in the Future*

Dmitri Trenin, August 27, 2012

Two former empires, often in conflict with one another, now have an opportunity for a common cooperation in the area of their interests and there already are rudimentary forms of such a cooperation, is the opinion of Dmitri Trenin, Director of the Carnegie Moscow Centre. His analysis, although still too cautious, should switch the red alarm light in Brussels on because it will have a direct impact on the development of the common European foreign policy. This is also a red light for all those EU member states who were subordinate to either of the two empires or both. Dmitri Trenin retired from the Russian army in 1993. He served in the army forces of both the Soviet Union and Russia from 1972 to 1993, including in his capacity as a liaison officer in the External Relations Branch of the Group of Soviet Forces (stationed in Potsdam) and as a staff member of the delegation to the US-Soviet nuclear arms talks in Geneva from 1985 to 1991. He analyses the Russian-Turkish relations in the light of the Syrian crisis and the frozen conflicts in the Caucasus.

Two former empires, often in conflict with one another, now have an opportunity for a common cooperation in the area of their interests and there already are rudimentary forms of such a cooperation, is the opinion of Dmitri Trenin, Director of the Carnegie Moscow Centre. His analysis, although still too cautious, should switch the red alarm light in Brussels on because it will have a direct impact on the development of the common European foreign policy. This is also a red light for all those EU member states who were subordinate to either of the two empires or both. Dmitri Trenin retired from the Russian army in 1993. He served in the army forces of both the Soviet Union and Russia from 1972 to 1993, including in his capacity as a liaison officer in the External Relations Branch of the Group of Soviet Forces (stationed in Potsdam) and as a staff member of the delegation to the US-Soviet nuclear arms talks in Geneva from 1985 to 1991. He analyses the Russian-Turkish relations in the light of the Syrian crisis and the frozen conflicts in the Caucasus.

Moscow and Ankara take vastly different views of the developments in Syria. Yet, the Russian government and the Kremlin-friendly media only rarely chide Turkey for the position it has taken on Syria. At the height of the battle in Damascus, Prime Minister Erdogan travelled to Russia for talks with Vladimir Putin. It is clear that Moscow considers Ankara not only an economic partner, but also a key regional player, and is prepared to work with it. Thus, an interesting relationship is emerging, one which may impact on a range of countries that once used to be part of either the Ottoman or Russian/Soviet empires, or both.

Moscow clearly appreciates Turkey's new strengths—economic, diplomatic, military, and its soft power. Even as the Soviet Union unravelled and the new Russian Federation underwent a difficult and painful change, Turkey rapidly urbanised and industrialised, its GDP rising tenfold, and its exports growing a hundredfold. Russia acknowledged, with visible satisfaction, Turkey's redefinition of its relations with the United States toward more autonomy from Washington. Moscow also noted, with clear  interest, that Turkey's membership in the European Union started to look increasingly unlikely.

interest, that Turkey's membership in the European Union started to look increasingly unlikely.

Turkey's current "neo-Ottoman" foreign policy in the neighbourhood has been more controversial, from the Russian perspective. Turkey rediscovered its interest and gained a measure of influence in the Balkans, the Black Sea area, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Over time, however, Moscow has grown more relaxed about what Ankara could actually achieve there beyond expanding trade relations. In addition, Russia's foreign policy philosophy usually recognises other great powers' legitimate security interests in their own regions, even as it vehemently opposes what it calls U.S. global meddling.

As a result, the Russo-Turkish relationship has fundamentally improved since the breakup of the Soviet Union ... You can continue reading the analysis here.

*The title is euinside's

Donald Tusk, Boyko Borissov | © Council of the EU

Donald Tusk, Boyko Borissov | © Council of the EU | © Turkey Presidency

| © Turkey Presidency Elmar Brok | © European Parliament

Elmar Brok | © European Parliament Boyko Borissov, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU

Boyko Borissov, Donald Tusk | © Council of the EU Boris Johnson | © Council of the EU

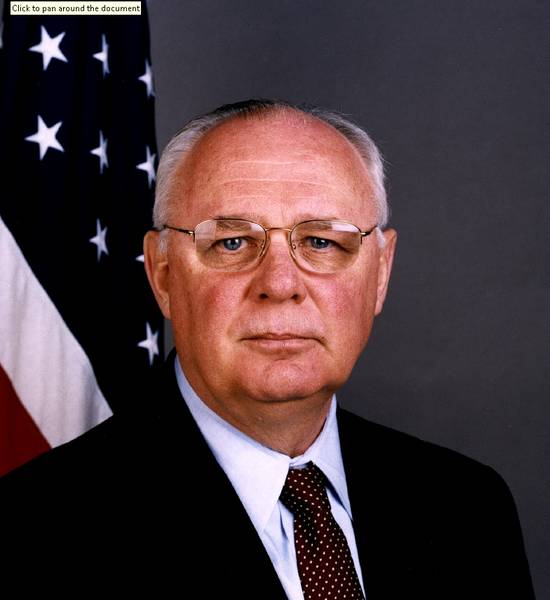

Boris Johnson | © Council of the EU James W. Pardew | ©

James W. Pardew | ©