Europe's Future Depends on Knowledge

Adelina Marini, February 28, 2012

Almost two years ago I wrote an article, which I titled "It's the education, stupid!", a paraphrase of the famous remark in the US during Bill Clinton's presidency "It's the economy, stupid!". Now, again I would like to use this title because time and time again we come to the conclusion that without good education our economies are doomed. The good news is that the topic is a major one in the current 10-year economic strategy of the EU, Europe 2020, but the bad news is that the problem started drawing attention 2 whole years after the presentation of the strategy. And the results from its implementation, in that part concerning education and training, are worrying and incline to thinking that Europe 2020 goals will not be achieved.

Almost two years ago I wrote an article, which I titled "It's the education, stupid!", a paraphrase of the famous remark in the US during Bill Clinton's presidency "It's the economy, stupid!". Now, again I would like to use this title because time and time again we come to the conclusion that without good education our economies are doomed. The good news is that the topic is a major one in the current 10-year economic strategy of the EU, Europe 2020, but the bad news is that the problem started drawing attention 2 whole years after the presentation of the strategy. And the results from its implementation, in that part concerning education and training, are worrying and incline to thinking that Europe 2020 goals will not be achieved.

The goals

One of the main goals of the Europe 2020 strategy, outlined during its presentation by President Barroso in the beginning of 2010, was the EU to avoid a "lost decade" because of the crisis, low economic growth and high unemployment. This is why, among the five goals the document puts forward, there are two that are directly related to education policies: 3% of Europe's GDP to be invested in science and research; the share of early school leavers (ESL) to drop below 10% and 40% of EU's youth to have graduated high school or to have university education. There is also a third, very important, goal and it is 75% employment of the population between 20 and 64 years.

According to a European Commission report from December 2011, even before the crisis the expenditure for education in some member states were quite low - near or under 4% of GDP, while EU average is almost 5% of GDP. Unlike USA where the public spending for education is 5.3% of gross domestic product. The spending for science and research, though, is quite low in many member states and is in contrast with the data of the Nordic countries - fully commensurable to their economic achievements - most Scandinavian countries and Germany spend more than 3% of their GDP for science and research, while many other countries, Bulgaria among them, spend symbolic amounts of money.

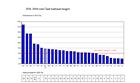

And as regards the other important indicator, which I will focus on later, this is youth unemployment, which emerged as a major problem in the past year. The number of young people in the EU without jobs or not involved in education, at the age of 15-24 years, has increased from 15.5% in 2008 to 20.9% in 2010 and these data do not seem striking at all on the average. Much more shocking are the data on national level. For example, youth unemployment in Ireland has jumped from 9 per cent in 2007 to 29 per cent now. This is a mind blowing jump, which is a huge problem for the country, which explains it with the construction bubble bust that left all these young people in the street with no jobs or education.

Another striking thing is the number of dropouts from school who are jobless - more than half of them (53%). The report says quite clearly that against the backdrop of these data, achieving the Europe 2020 goals - the share of 18-24 year-olds that have left school earlier to be reduced to below 10% by 2020 - becomes quite critical. "If current trends continue, this target will not be reached". In 2010 the average number of ESL in the EU was 14.1%. The bigger problem, though, is that many member states do not base their policies on sufficiently new data and analyses for the reasons for early school leaving. There are several countries that systemically collect data, which they update and analyse - Estonia, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Britain.

And another sad fact, related to ESL - prevention and early intervention are the key to solve the problem, "however, Member States devote too little attention to prevention". The member states in general were mainly focused on austerity measures and just since a month ago on European level it is being actively talked about accompanying these measures by a growth and jobs plan. The plan is available, as far as a common  European strategy can be specific. It is yet to be seen how it will be implemented and for the sake of what.

European strategy can be specific. It is yet to be seen how it will be implemented and for the sake of what.

Youth unemployment means social exclusion

On February 10 a very interesting meeting of the ministers of education, culture and sports of the EU took place, during which it was decided by the Danish Presidency every member state to present the measures and strategies it implements to tackle youth unemployment and early school leaving, because the two things are directly related. What was very clearly outlined during the debate was that most Nordic countries shared their experience, based almost entirely upon the German dual system (going to school and in parallel apprenticeships in a private company), while many of the new member states emphasised on the need for more mobility within the EU both for students and for people who wish to receive additional professional training.

During the debates several very sincere statements were heard of representatives of countries, suffering from severe economic troubles. For example, the words "youth unemployment means social exclusion" are of the Greek deputy permanent representative to the EU. The events in Greece in the past few months give some solid grounds for fear of a "lost decade". Greece is the country with very high youth unemployment.

In fact the problem is much deeper than simply to respond to the statistical data for youth and general unemployment. And this problem goes hand in hand with the current troubles the EU as a whole is experiencing, while trying to find a solution to the eurozone debt crisis, to the lack of competitiveness in a large part of the economies in the Union, to the ageing population and the strong pressures on the social systems of the member states. And solving this problem does not require simply long term actions and efforts but a common European approach. At the moment, general education policies are entirely within national competences. The level of economic interconnectedness, though, shows us that in no way these problems can be solved unilaterally.

Probably you have no doubt that the German model, presented during the session of the Education Council on February 10 by Mr Helge Braun, parliamentary state secretary of the federal minister of education and research, was highlighted as an example a number of times as being most effective. Most of the speakers were unanimous that the German model was more than successful. Including Minister Ћeljko Jovanovic of Croatia, which currently has an observing status in the Councils of the EU but as this was a public deliberation, he also got the word.

What is the German model?

This is a dual system, which combines professional training with basic education. The goal, which at this stage is successfully achieved, is in the end of the education process a young person to be willing and ready to start work. Statistics are more than impressive: 60% of German young people take part in these programmes, which is why the level of youth unemployment in Germany is 8.1%, which is much below EU average. It is important to note, however, that the private firms respond en masse and take part in the programme, although they pay for the education of students themselves. It provides for students to spend 3-4 days at work in a private company and 1-2 days at school. Depending on the type of training it could last 2-3 years and 57% of the participants in the programme are then successfully realised on the labour market. The programme covers 350 professions, but expansion is envisaged.

This is a dual system, which combines professional training with basic education. The goal, which at this stage is successfully achieved, is in the end of the education process a young person to be willing and ready to start work. Statistics are more than impressive: 60% of German young people take part in these programmes, which is why the level of youth unemployment in Germany is 8.1%, which is much below EU average. It is important to note, however, that the private firms respond en masse and take part in the programme, although they pay for the education of students themselves. It provides for students to spend 3-4 days at work in a private company and 1-2 days at school. Depending on the type of training it could last 2-3 years and 57% of the participants in the programme are then successfully realised on the labour market. The programme covers 350 professions, but expansion is envisaged.

The debate showed that this system works very well also in Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland and other Nordic nations but it is difficult to be realised elsewhere. A very strong and sincere statement in this regard made the Irish minister of education, Ruairí Quinn. He highlights several very strong arguments, which deserve special attention not only in the case of Ireland. "I am a great admirer of the German system but it doesn't necessarily translate efficiently and effectively to countries that have largely rural or agricultural background", Mr Quinn said. In his words the problem is much deeper, because other, often ignored by policy makers factors need to be addressed, like when education is not valued at home it is not valued among the kids, who reluctantly go to school. This is why, he said, when adjusting our education systems families have to be involved too.

He contributed significantly to easing the atmosphere in the Council by mentioning something, which seems funny at first glance and indeed cheered up the ministers, but in fact is a very serious issue. Young boys, he said, often drop out from the education system because they are bored. They do not visit libraries, where prevailing is that type of literature that "evokes mostly the female romantic side in us". Quite often these young men need simple literacy, which can be achieved by offering more sports literature that would draw boys' interest and will in the same time increase their literacy. This opens a huge topic - about updating education content and its adjustment to the needs of the children born and living in the 21st century.

As it seems, this problem exists not only in Ireland, as Christine Antorini, Minister for Children and Education of Denmark, said. "We have the same problem with romantic literature but since recently we have a literature prize for boys", she added.

Slovakia's representative pointed out that the German system was impossible to be applied in his country because firms refused to take students and the pupils themselves often left the companies after finishing their training. The Slovak education minister said that the main problem was with the availability of accurate information about the past, current and future needs of the labour market. More important is this information to be on a EU level because this would boost competition among schools. "Our schooling  system needs information from other countries because we prepare our young generation to work on the entire market".

system needs information from other countries because we prepare our young generation to work on the entire market".

Slovenia is one of the good examples of a successfully applying new practises new member state, although the level of youth unemployment is constantly growing since 2000. The problem of Slovenia's young people is that they find it difficult to decide what they want to work. According to the German minister of education this can be easily solved by introducing professional training very early in school. There is another problem, very well described for the US too - the number of science students is constantly dropping for the benefit of growing interest in literature and arts. The Slovenian representative also said that gaining international experience is of great importance.

Bulgaria is among the countries with very serious problems because the level of youth unemployment is almost 24%. Petya Evtimova, deputy minister of education, explained that a National Employment Plan was adopted for 2012, which included the initiative "Work for the Young People of Bulgaria". In January a programme has been launched, financed with 50 mn euros by the European Social Fund for apprenticeships, which are expected to cover 120,000 pupils and students in the next 2 years.

It's good that Denmark presides over the Council

The EU repeats for many years that Europe's bright future depends on whether it will succeed in building a knowledge based economy. This was a major focus in the previous 10-year economic strategy of the Union, and now, although with different wording, it is present in the current Europe 2020. It is obvious, however, that the member states' economies are in various evolution stages for many reasons but their education systems also vary quite much and produce different results. This is why it is good that at the moment Denmark is at the helm of the EU - a country with solid traditions in fast adaptation to a changing world. It has to be immediately noted, though, that nothing of what Denmark is achieving, can be done without money. And when the size of taxes is considered, it is good to assess one competitive advantage what financial returns can produce instead of another.

As Thomas Friedman writes in his book "The World is Flat", an ideal country in a deeply globalised (flat) world is a country with little natural resources because they generally tend to dig deeper in themselves. They try to extract the energy, entrepreneurship., creativity and intelligence from their people. Denmark is doing precisely this. How? By providing its youth access to high education and possibilities to gain experience abroad. This is the main thing, by the way, which can be drawn as a lesson from the Danish experience. Since 2007 the universities in the country have been reduced from 25 to 8 and 3 research institutes. I underline this especially because of the latest fashion in Bulgaria any kinds of universities to pop up around the country.

As Thomas Friedman writes in his book "The World is Flat", an ideal country in a deeply globalised (flat) world is a country with little natural resources because they generally tend to dig deeper in themselves. They try to extract the energy, entrepreneurship., creativity and intelligence from their people. Denmark is doing precisely this. How? By providing its youth access to high education and possibilities to gain experience abroad. This is the main thing, by the way, which can be drawn as a lesson from the Danish experience. Since 2007 the universities in the country have been reduced from 25 to 8 and 3 research institutes. I underline this especially because of the latest fashion in Bulgaria any kinds of universities to pop up around the country.

Besides, it is very important to note how these universities are funded - mainly by block funding and external incomes. The former is provided by the state and is being distributed for each university through the budget. For the rest the universities themselves take care. Students do not pay tuition fees for full degree programmes but more - they get monthly state grants, being at disposal from the moment a Danish child turns 18 years of age. The value of these grants is from 6,000 euros to 16,000 euros. What astounded me was that the state grants can be provided for studying abroad. The Danish government provides grants for foreign students too - from the EU and outside.

All representatives at the Education Council on February 10 were unanimous that the exchange of opinions and good practises was extremely useful. Even more useful it would be if we are all aware what the outcome of our investments in education is. A good example in this regard are the British. Their representative said, for example, that under the apprenticeship programme, which is very successful in Britain, for every invested by the government pound there was a return of 18 pounds.

| © European Union

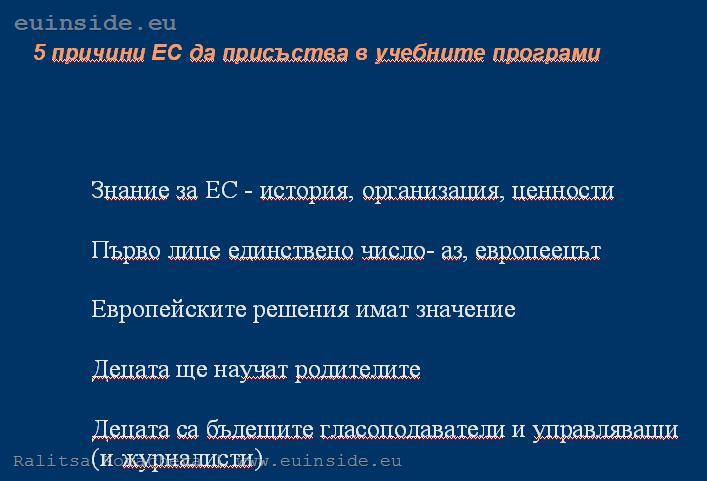

| © European Union | © euinside

| © euinside Krasimir Valchev | © Council of the EU

Krasimir Valchev | © Council of the EU | © euinside

| © euinside | © EU

| © EU | © EU

| © EU